Darío Oses

Journalist and Master in Latin American Studies (University of Chile). Director of the Pablo Neruda Foundation Library.

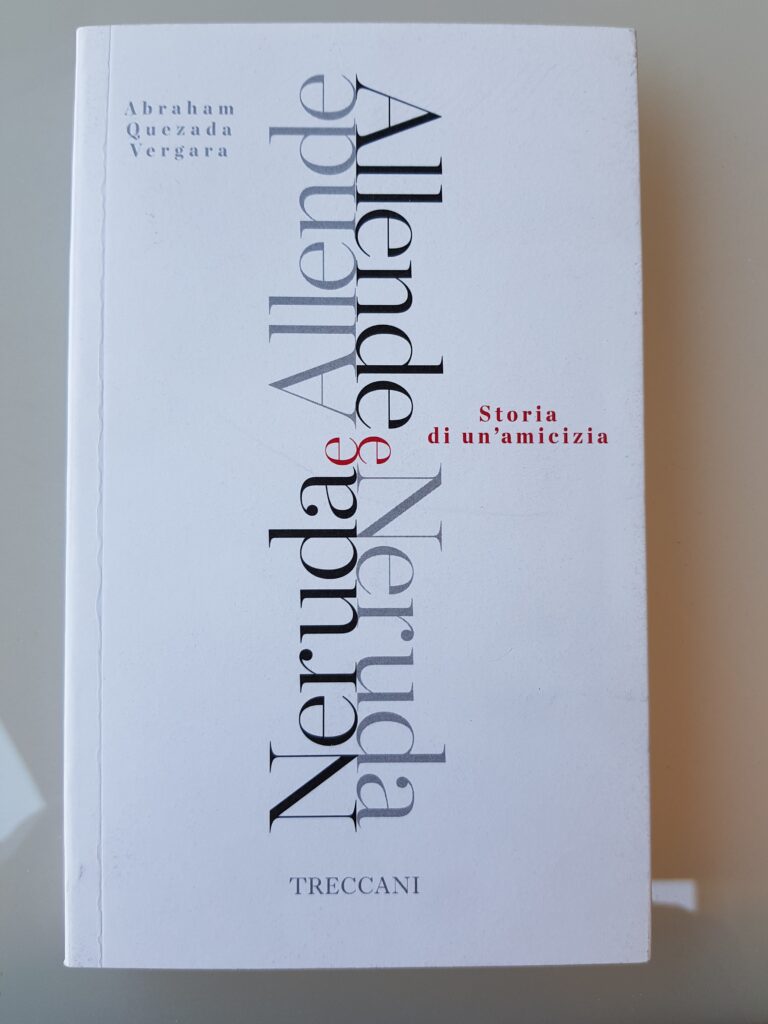

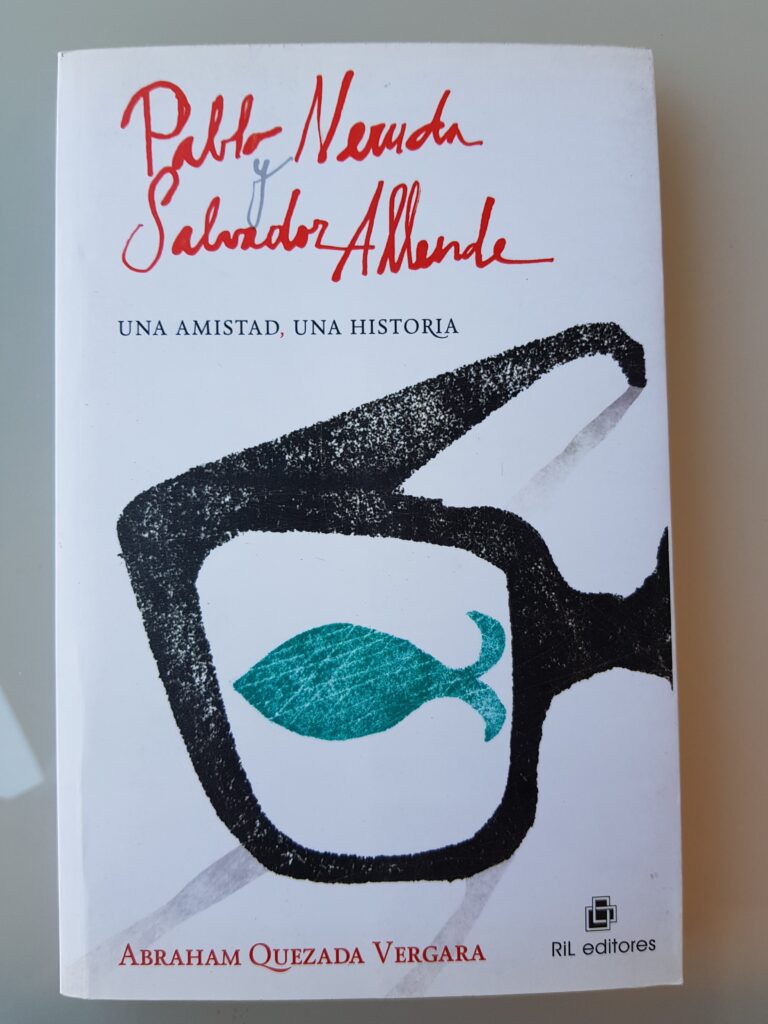

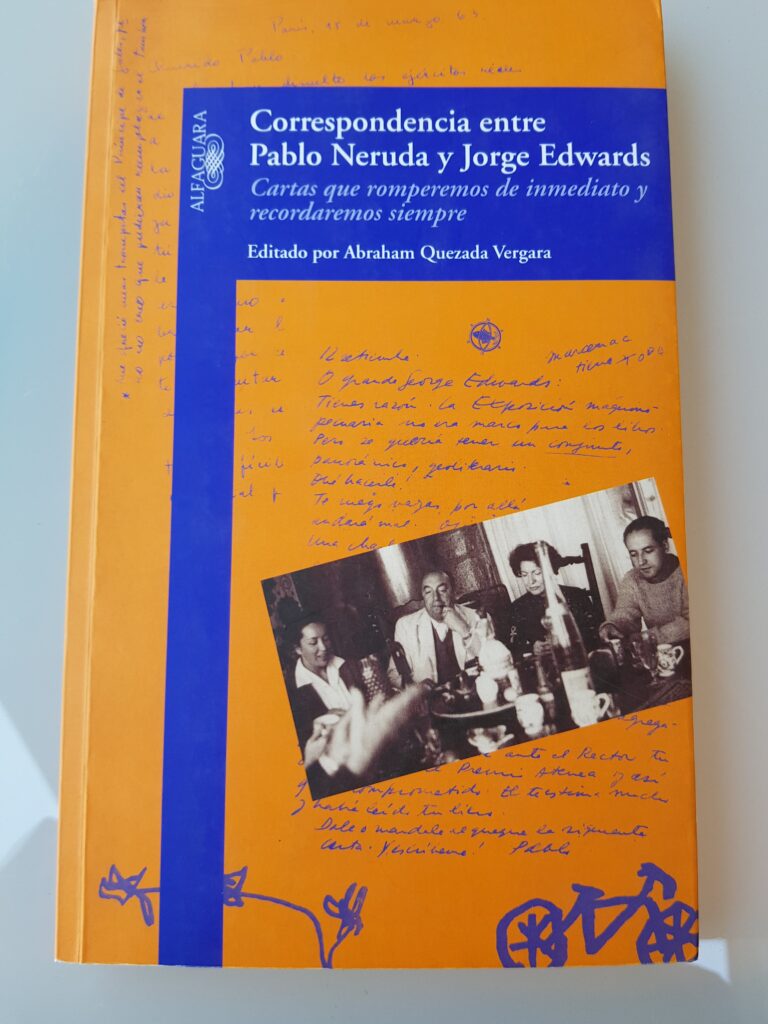

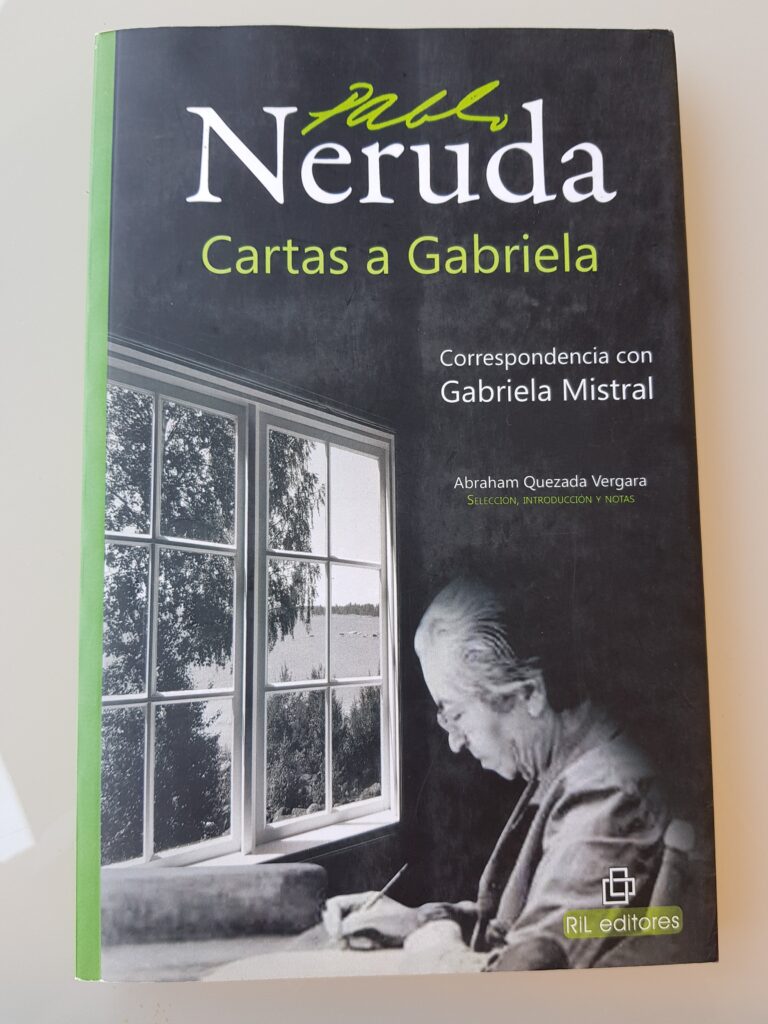

Writer and diplomat (Antofagasta, 1961). Professor of History and Geography graduated in Diplomacy. Master in International Relations and Doctor in American Studies. Researcher specialized in the biographical dimension of Pablo Neruda with important articles and books published both in national and foreign media. One of them, Allende – Neruda, a friendship, a story, with several editions in Spanish and translated into Italian by Treccani, one of the most prestigious publishers in Italy. A Chinese edition is also in preparation. A British publication has considered it as The world’s leading authority on the letters of Pablo Neruda (Cantalao N ° 1, London, Septembre, 2013).

Video transcription Abraham Quezada

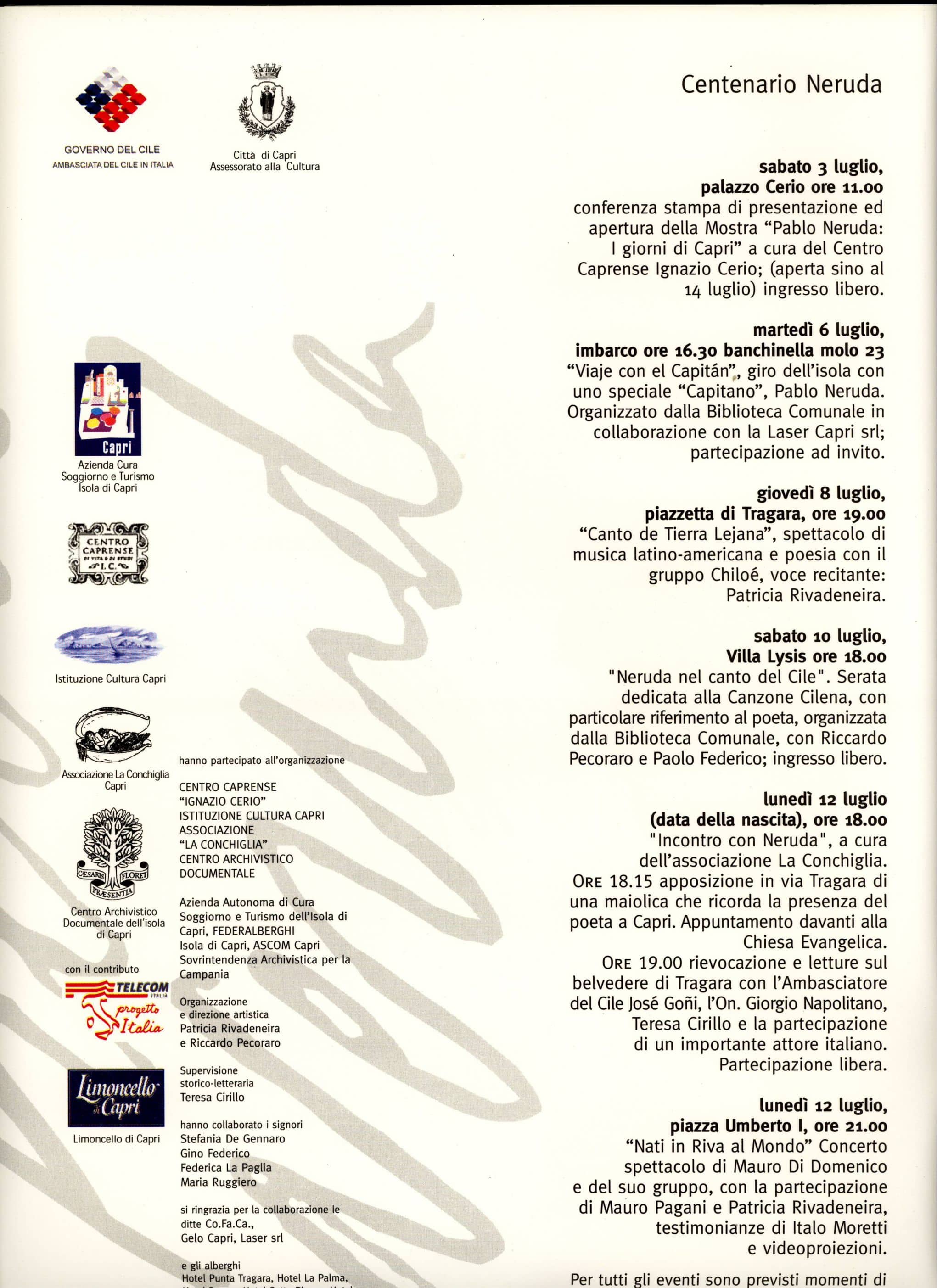

Good afternoon, my friends. From the viceroyalty capital, from Lima, from Peru, I would like to extend an affectionate greeting to the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and the Tuscan Bibliographic Society of Italy, who have organized this magnificent exhibition, the first Chilean-Italian virtual exhibition “Pablo Neruda: 50 years Nobel Prize in Literature 1971-2021 “. And in that sense, I take the opportunity to greet and also thank the institutions that have contributed to this: the General Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile stands out, the place where I work, and in Italy, the Library from the Ignazio Cerio Caprense Center, a place that I visited a few years ago.

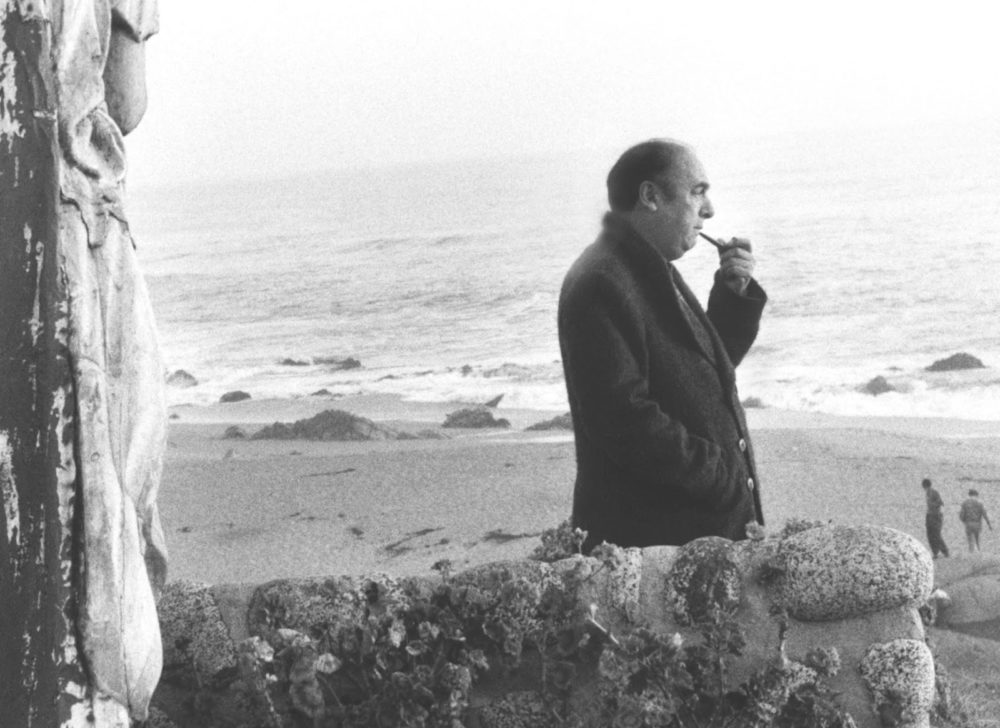

Undoubtedly, this exhibition is a relevant, extraordinary and, I would say, even endearing exhibition of Neruda, because it shows us the bibliophile Neruda, one of his great passions. Neruda and his collections in Chile and, finally, Neruda in Italy. These three spaces are spaces much loved by the poet and that he developed to the full.

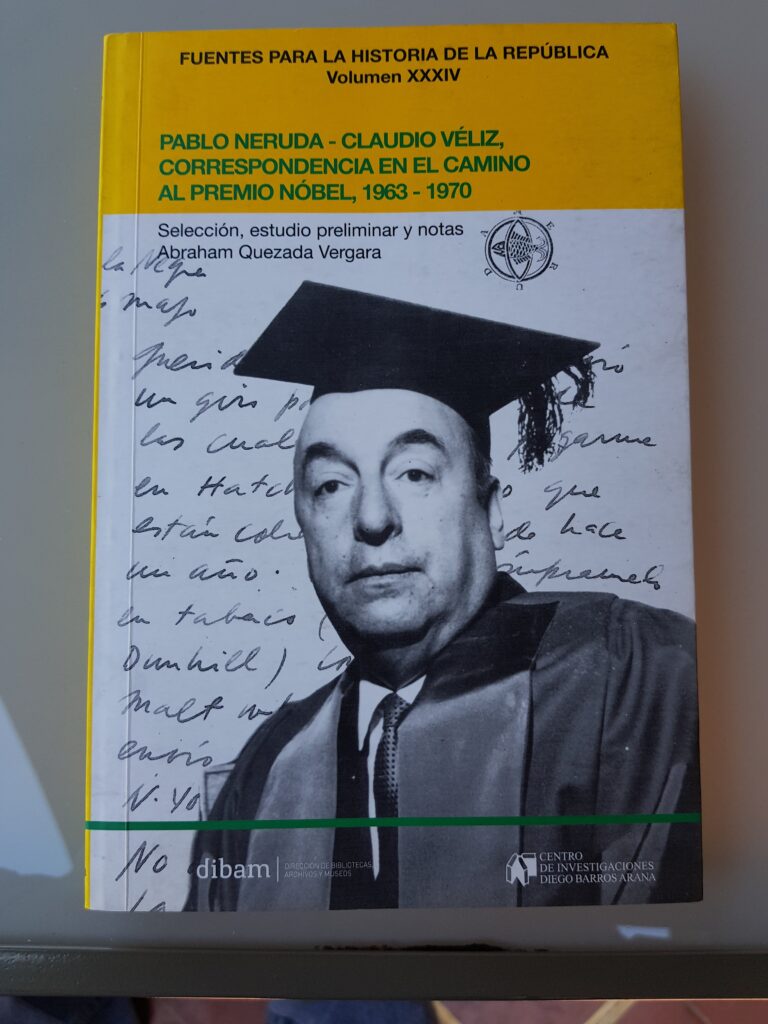

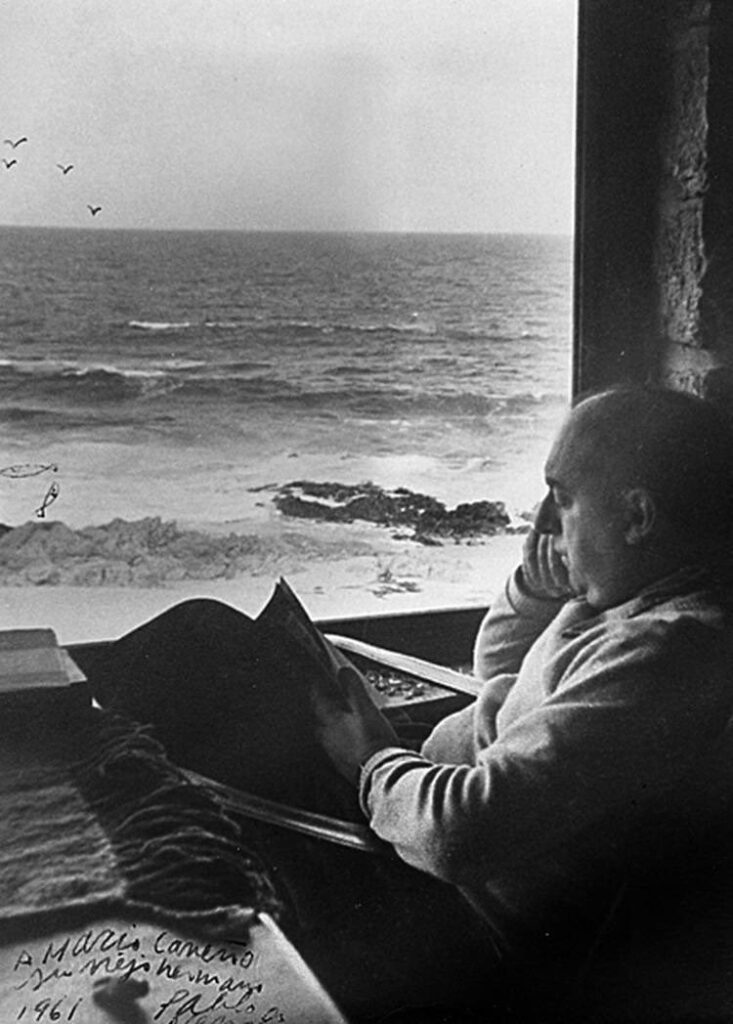

In his role as a bibliophile, for example, I just want to tell you two anecdotes that I had the privilege of bringing to light in some of my published works. One of them is the intense correspondence that the poet carries out with the Chilean academic Claudio Veliz so he can get for him in London an old and very valuable book entitled Travels whose author is Amasa Delano, where in August of 1963 he tells him that he is willing to pay “whatever they ask of him” and in November of that same year, that is to say, a few months later, he adds: “I burn with the desire to see and feel that book.” This was an acquisition that ultimately came to fruition and the poet received the book. When he received it, he held a reception in Isla Negra with all his friends and he was immensely happy.

Another similar anecdote is his desperate and insistent attempts, through his Peruvian friends, to acquire an original copy of Flora Tristán’s book, Peregrinaciones de una Paria, that book from 1838, in its original edition, in French. There were other editions in Chile. Even Ercilla Press, in the 1940s, had published one edition and there were another two more published that the poet could perfectly read. But no, he wanted the original French edition, and why did he want it so much? Because apart from the taste of the old book, of smelling, touching, feeling, as he says in one of his letters, Flora Tristán recounted her passage through Valparaíso and the lies and anecdotes that were circulating in our historic port at that time. Therefore, the poet wanted it in its original edition.

Therefore, this documentary contribution that you are making, with so much care, with so much love, comes, I believe, to justly celebrate Neruda’s intellectual effort and his love for books, while giving an account of his intense poetic world where there is still much to discover.

Luckily for us researchers and scholars, the Neruda`s universe is an expanding universe and the contribution that the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles is making of exposing it very professionally and sharing it, which is the ultimate goal that all people and institutions should have, who are dedicated to it, it is a truly remarkable effort.

If the poet were alive, without a doubt, he would be happy with this initiative, hopefully it will have a second, a third, a fourth and successive versions from now on.

To finish, just a reflection on Neruda and the Nobel Prize.

You well know that Neruda’s Nobel Prize was the second Nobel Prize for Chile and the third for Latin America, after Mistral’s in 1945 and Miguel Ángel Asturias’s in 1967. But Neruda had been a candidate for this recognition since late from the 40s.

In 1964, the poet was deeply moved when he learned of the resignation of the prize that Jean Paul Sartre had made. In the letter that this French philosopher sends to Stockholm, among other arguments, he says “I am not worthy of winning this award until it is given to poets like Neruda.”

Finally, the poet got it. And why did you get it? He got it, without a doubt, because of his talent and his career. But he also got it because of his persistence, because he was tenacious, and he believed and was convinced that he deserved it. So it is with these types of samples, I believe that they account for such a rich expanding universe, I repeat, that Neruda, luckily for all of us, continues to offer us these joys.

Thank you very much for the work done, I send you a warm greeting from Lima. Thank you.

Italian singer-songwriter, very loved by the Chilean public. He won the popular music competition at the LVI Viña del Mar International Song Festival in 2015.

Poem 20

Hello friends, I am Franco Simone and I am a singer-songwriter, but I am also a huge admirer of Pablo Neruda’s poetry. In addition, I would add that Pablo Neruda is, absolutely, my favourite poet.

Exactly 50 years have passed since the Nobel Prize was awarded to this great poet. I invite you all to visit the Italo-Chilean virtual exhibition “Pablo Neruda: 50 Years of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1971-2021)”.

What would you say about this poet? I have always admired his originality, his great spirituality, which became something carnal. He always knew how to unite spirit with eroticism. At times, he seemed not very modest, but without ever being indecent or transgressive. There is always something to learn when reading Neruda. Today I wanted to read some verses from his beautiful Poem 20:

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

Write, for example,’ The night is shattered

and the blue stars shiver in the distance.’

The night wind revolves in the sky and sings.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.

Through nights like this one I held her in my arms

I kissed her again and again under the endless sky.

She loved me sometimes, and I loved her too.

How could one not have loved her great still eyes.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the immense night, still more immense without her.

And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture.

What does it matter that my love could not keep her.

The night is shattered and she is not with me.

This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance.

My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

My sight searches for her as though to go to her.

My heart looks for her, and she is not with me.

The same night whitening the same trees.

We, of that time, are no longer the same.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her.

My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing.

Another’s. She will be another’s. Like my kisses before.

This is Pablo Neruda

Since 1990, she has been a librarian at the Ignazio Cerio Capri Centre. Carmelina graduated in Modern Foreign Languages and Literature from the Oriental University Institute of Naples. She has researched the subject of English writers and travellers on Capri, also publishing numerous articles on the subject. For the Capri Centre she has been the Curator of the exhibitions “History of an Island and a Library”, “The Pagano Hostel: a family, their house, their guests”, “Three Centuries of Travellers in Capri”, and “Capri and the World in Drawings by Laetitia Cerio “.

Capri, reina de roca

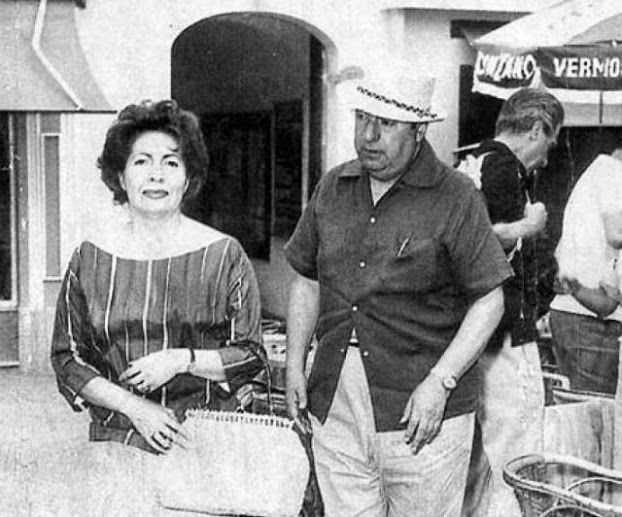

It was a dark winter evening when Pablo Neruda and Matilde Urrutia arrived at “Arturo’s Casetta” in Capri. Edwin Cerio, who had made the house available for them, welcomed them at the light of the fireplace. A few days before, on 8 January 1952, the member of the Italian parliament Mario Alicata had written a heartfelt letter to Cerio, asking him to host the poet: “The great poet Pablo Neruda is in Naples and wishes to spend three months in Capri in order to finish his book on Italy (…) He would prefer living in a house, even a very tiny one, and not in a hotel or guesthouse (…) Perhaps I hope not to dare too much, could you see if you have one or two rooms available, somewhere?”

Edwin replied directly to Neruda, with a simple invitation telegram: “Come, I’m waiting for you in Capri. There is a villa, “Arturo’s Casetta”, ready to host you. There you will be undisturbed and you will have the possibility to finish your book and to rest”.

The six months they spent in La isla clandestina, as Neruda calls Capri, are documented by the epistolary between Edwin and Pablo, now preserved in Capri at the library of the “Ignazio Cerio” Centre. Such correspondence consists of 14 documentary units, mainly letters from Neruda, but also letters from Mario Alicata, as well as the minutes of some letters from Edwin, and an article celebrating the poet’s arrival on the island: “looking forward to your landing in a place where no curtain- of whatever metal- could be seen, and that has its borders only in the horizons of poetry and beauty” . Also there was an extraordinary invitation card “a beber una copa …” in tissue paper with Edwin’s face stylized on it, that was delivered on 25 March1952 to the owners of “Arturo’s Casetta”, invitation card that they luckily preserved. Most of the letters are written on rice paper bought in China and adorned with elegant designs of dragonflies, flowers and an ideogram: “it is my signature, in Chinese it means ‘three ears'”.

Edwin and Claretta Cerio were living across the road from Pablo and Matilde; the former lived in Villa Lo Studio, located right in front of “Arturo’s Casetta”, both were on via Tragara. They wrote to each other and the maid of both, Amelia, acted as “post woman”. They continued to write to each other also when Neruda and Urrutia moved to Via Li Campi, in a small house closer to the historic centre but certainly without the breathtaking view they had enjoyed in Marina Piccola. Apart from dealing with day to day issues and sometimes requesting advice, those letters clearly show the sense of hospitality, the commonality of interests, the curiosity for Edwin’s shell collections, the serenity that pervaded the couple and the inspiration that Neruda finds in the island’s natural beauties.

The letters between the two also reveal an incident that risked to undermine the relationship of esteem established between the guest and his landlord. Cerio, in making his home available, had established the condition that the poet – during his island stay – left apart his role as a communist militant. However, when he received a phone call from a Chilean who, arriving in Naples, asked him to speak with Neruda, he became worried and wrote to the poet: “I was very happy to make “Arturo’s Casetta”, available for you… it is in the tradition of Capri, of my family and of my small cultural centre to honour people of genius and intellectuals without asking them for any passports other than their work (…) as far as I am concerned, I have the shortcoming of disliking all sorts of politics (…) therefore, as I do not wish to sail under a false flag, I do beg you and your friends not to ascribe any political intention or manifestation to the hospitality I offered you”. The poet apologized for the inconvenience and assured that no political activity had taken place “as for your flag, I already knew it, a flag that rises with the colours and scents of your island” and promised him that there would be no more problems. And so it was.

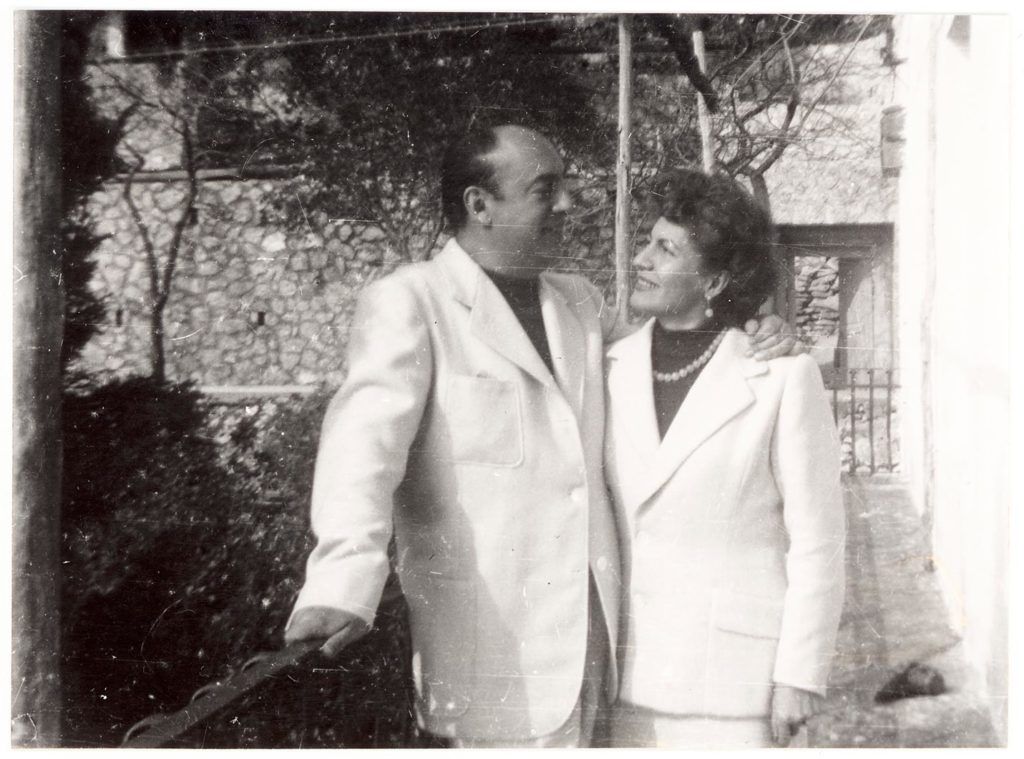

On the island there was no reason for secret encounters with Matilda, as Delia del Carril was on the other side of the planet: they felt finally free to love each other, to do long walks to Anacapri climbing up the Phoenician Scale and to organize parties with their friends from of Rome and Naples. Pablo also devised a peculiar ceremony so that the love that bound them would be blessed by Capri’s moonlight.

Cerio – among other things – was fond of the island’s nature and Neruda was for him an interested interlocutor. For this he wanted to present the poet with a booklet of his, dealing with the blue lizard from Faraglioni, that had been printed on “Amalfi paper” and was at the time out of print. The present was extremely welcomed by Neruda..

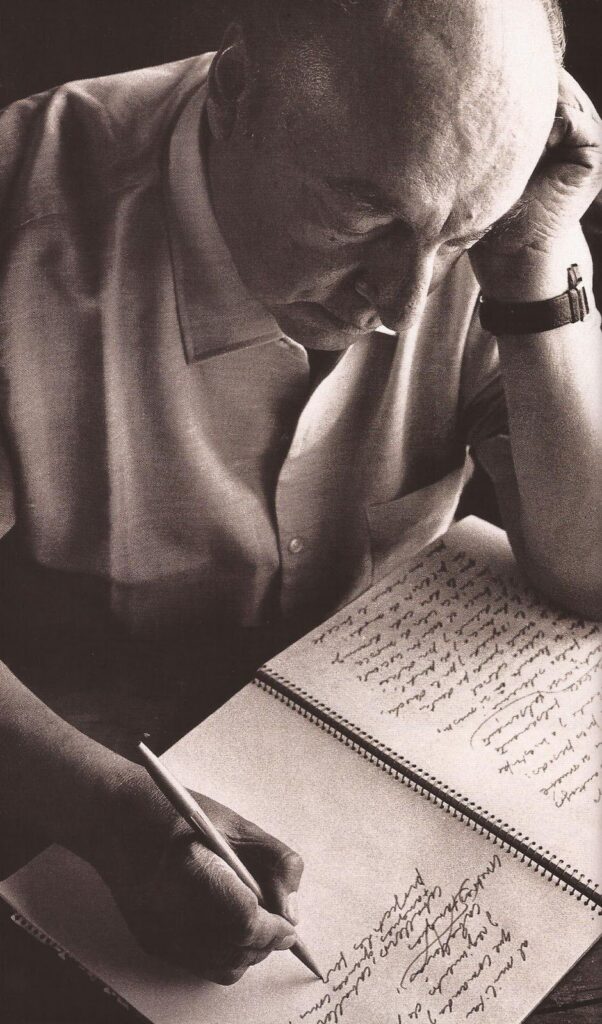

When thanking his friend, Neruda made him apart of a project he has in mind: the publication of a book of poems dedicated to Matilda, Los Versos del Capitan. Quiet and peace on the island were ideal in order to allow him to finish his work. This collection will be published anonymously later on, by Paolo Ricci in July 52, when the poet had already left for Chile. It was published only in 44 copies out of commerce, each with the name of a subscriber. Apart from Cerio, there were Quasimodo, Guttuso, Giorgio Napolitano, Vasco Pratolini Palmiro Togliatti, Luchino Visconti, Giulio Einaudi, Renato Caccioppoli. To go today through that list (included before colophon at the end of the volume), it is like to reading a chapter of the history of this country.

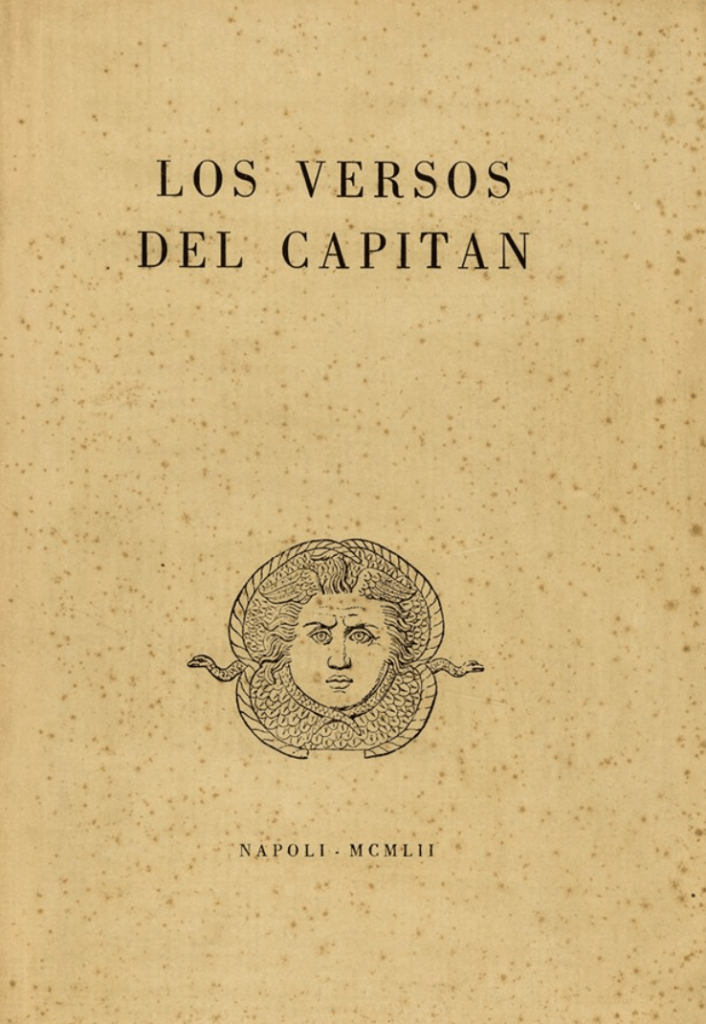

The last letter to Edwin and Claretta, the one written when the poet was already sailing back to Chile on the motor ship Giulio Cesare, after Scelba had not renewed his residence permit, expresses the gratitude of Pablo and Matilde and their affectionate greetings to their friends in Capri. Friends that were not going to be forgotten after the return in Chile and were going to be the recipients of kind presents even thereafter.

Bibliography:

[Pablo Neruda], Los Versos del Capitan, Napoli, Arte Tipografica, 1952

Pablo Neruda, Confesso che ho vissuto, Milano, SugarCo, 1974

Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Neruda a Capri, sogno di un’isola, Capri, Edizioni La Conchiglia, 2001

Teresa Cirillo Sirri (a cura di), Matilde Urrutia: La mia vita con Pablo Neruda, Firenze, Passigli, 2002

Pablo Neruda, L’uva e il vento: poesie italiane, a cura di Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Bagno a Ripoli, Passigli, 2004.

Bibliografía:

- [Pablo Neruda], Los Versos del Capitán, Napoli, Arte tipográfica, 1952.

- Pablo Neruda, Confesso che ho vissuto, Milano, SugarCo, 1974.

- Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Neruda a Capri, sogno di un’isola, Capri, Edizioni La Conchiglia, 2001.

- Teresa Cirillo Sirri (a cura di), Matilde Urrutia: La mia vita con Pablo Neruda, Firenze, Passigli, 2002.

- Pablo Neruda, L’uva e il vento: poesie italiane, a cura di Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Bagno a Ripoli, Passigli, 2004.

Cover of Los Versos del Capitán, Napoli, 1952.

First edition of the Captain’s verses: list of the 44 original subscribers

| 1 | Matilde Urrutia | 23 | Paolo Ricci |

| 2 | Neruda Urrutia | 24 | Antonello Trombadori |

| 3 | Pablo Neruda | 25 | Giuseppe De Santis |

| 4 | Biblioteca Caprense | 26 | Ivette Joie |

| 5 | Claretta Cerio | 27 | Vittorio Vidali |

| 6 | Ilya Ehremburg | 28 | Luigi Cosenza |

| 7 | Elsa Morante | 29 | Carlo Bernari |

| 8 | Vasco Pratolini | 30 | Pietro Ingrao |

| 9 | Giulio Einaudi | 31 | Armando Pizzinato |

| 10 | Jorge Amado | 32 | Mario Montagnana |

| 11 | Mario Alicata | 33 | Gaetano Macchiaroli |

| 12 | Editore Gaspare Casella | 34 | Ernesto Treccani |

| 13 | Nazim Hikmet | 35 | Francesco De Martino |

| 14 | Palmiro Togliatti | 36 | Alessandro Vescia |

| 15 | Luchino Visconti | 37 | Angelo Rossi |

| 16 | Renato Caccioppoli | 38 | Giuseppe Zigaina |

| 17 | Stephen Hermlin | 39 | Gianzio Sacripante |

| 18 | Elvira Pajetta Berrini | 40 | Massimo Caprara |

| 19 | Salvatore Quasimodo | 41 | Clemente Maglietta |

| 20 | Bruno Molajoli | 42 | Lino Mezzacane |

| 21 | Carlo Levi | 43 | Gerardo Chiaromonte |

| 22 | Renato Guttuso | 44 | Giorgio Napolitano |

Los Versos del Capitán, digitized

Letter from Pablo Neruda to Edwin and Claretta Cerio (July 6, 1962).

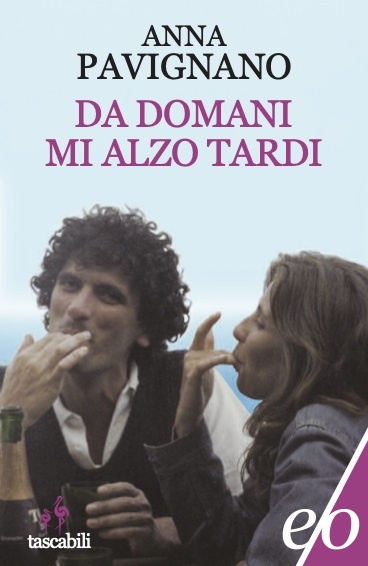

Writer and screenwriter. With Massimo Troisi, she writes several four-handed film scripts. The film “Neruda’s Postman” (1994), was nominated for an Academy Award, in various categories. As a writer, she has published ten novels, one of the most widely read by the public is “Da domani mi alzo tardi” (2009).

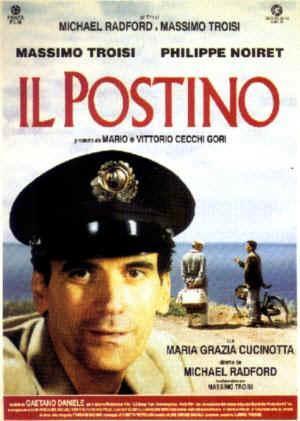

Neruda in the Italian cinema: The Postman (1994)

Antonio Skármeta wrote “Neruda’s Postman” in 1986 and in 1994 Michael Radford directed a film based on the book starring Massimo Troisi. This film had 5 Oscar nominations: Best Direction, Best Leading Actor, Best Non-original Screenplay, Best Production, and the statuette was won by Luis Bacalov for Best Soundtrack.

I had the opportunity to meet Antonio Skármeta in Italy, at the Turin Book Fair, after having first met him in the pages of his novel, when I made – together with Massimo Troisi and Michael Radford – the film adaptation. I kept the memory of a kind, gentle person and it seemed to me that the man corresponded perfectly to the artist, that the book belonged to him like his serenity, his smile, his lively gaze and the wonderful language in which he spoke, but which I did not understand. In this way, it was a meeting of sensitivity, of assumptions, of facial expressions that, however, left an unforgettable mark on me.

Nobody better than him could have narrated the private Neruda, nobody could have taken us to his house in Isla Negra, show it while he dances with Matilde or cooks with an onion in one hand and a knife in the other, transforming everything into poetry. And follow him later in his disenchantment at the news of the Nobel Prize, appreciated, but received with modesty, without self-celebration or vanity. He restored us to the man capable of listening to the forgotten, the same man who carried with painful empathy the voice of the miner, “a faceless creature, a mask of sweat, dust and blood” that he himself saw emerge from the viscera of the Chilean land. A simple postman, not very cultured, but with a keen sensitivity and many ideals, thanks to Skàrmeta’s pen he becomes the poet’s best confidant, the one who asks for consolation in exile, begging him to send him the sounds of the island. I have always wondered if that postman ever existed and, if not, in what fold of reality the author was inspired to invent such a true and credible character.

Massimo Troisi had an acute sensitivity, was a poetic soul, an author, a director, a talented Neapolitan actor, who in Italy is considered heir to the genius of Eduardo de Filippo. Troisi reads the book and falls in love with him. Precisely the idea of peering into the less obvious aspects of the soul of the Poet, being able to give reality to the life that hides behind a verse and, even more, to the beautiful but blinding light of the most prestigious prize in the world, the Nobel, led Troisi to the desire to make it the masterpiece of his own artistic and personal life. Of course, he could not foresee that the film would have wings so strong that it would fly abroad and reach the Oscars, but he put all the ingredients to make it exceptional: talent, passion, professionalism to which fate added a cross that Massimo embraced with courage and determination.

In the film we see everything, not only the artistic product, but the soul, which appears naked on the screen, as if the image, the hollow face, the slim body, were only the material medium of the impregnable interiority that permeates the character. “The Postman” was Massimo Troisi’s last film: he shot with the last force that a heart gave him awaiting a transplant. He stubbornly refused to postpone filming, to interrupt when he felt tired. One Friday in June he finished his work, greeted everyone, took the classic photo at the end of filming and said, “Don’t forget me.” On Saturday afternoon he fell asleep and left.

“The Postman” seems to unconsciously contain his own future, he has a sense of pain and the end of things that starts from the fiction of the story and the film to continue in real life in a resounding way. Fiction is painfully confused with reality. But in the film there is not only sadness, it is also governed by smiles and poetry, the same ingredients of the book, although the adaptation required many changes. A change of time, from 1973 to 1952, of the environment, from Chile to Italy, from the age of the protagonist who, from being a seventeen-year-old youth, becomes an ageless adult, but with dreams and aspirations intact and pure. Adapting the novel was fascinating. While the Postman, a character born of the writer’s creativity, allowed more freedom, Neruda asked for a job that had to be respectful of the greatness known to all. It was not always possible to make use of the novel’s dialogues, because many of the elements that make the character great on paper are narrated and not dialogued. How to make the poet speak in the film while still being at his height? The solution was “I confess that I have lived”, written by Neruda himself in first person.

Deepening in the words expressed by the Poet it was possible to build his dialogues. The character of Mario Jiménez, who in Italy becomes Mario Ruoppolo, in the novel has the freshness of youth, but finds its vivacity in the talent of Massimo Troisi. There are many licenses that must be taken to transform a good book into a good movie, such as inserting more than one fictional narrator in the story and forgiving yourself. However, there was an element in ‘Neruda’s Postman’ that really needed to be respected, the poem that in the end is saddened by the death of Pablo Neruda, which occurred during the Pinochet coup.

Yes, it was a fictional storyteller, but the poet certainly could not die twenty years in advance. Thus, to preserve the sense of loss that permeates the end of the story, it was inevitable that the Postman would die and that the condolences that are his in the novel would be instead of the Poet: Pablo Neruda, returning to the island where all the events had taken place, he discovers that his friend and confidant is gone forever. But there is his son, who was orphaned before he was born and who bears his name, Pablito. Unfortunately, that sense of death came out of fiction and into reality, with the death of Massimo Troisi a truly unfathomable void was created for all of us who knew him and for the public who loved him. Seeing this movie comforts us and at the same time it still hurts us to this day.

Editor.

As testimony of the bond between Neruda and the publisher, we have selected the transcription of the speech with which the Poet, on November 12, 1970, inaugurated the exhibition “Tribute to the Book and Alberto Tallone”, at the Italian Library of Santiago de Chile.

Homage to the book and to Alberto Tallone (1970)

When speaking of Gutenberg and the invention of printing, Lamartine coined this beautiful expression: “The printing press is the telescope of the soul …”. A telescope that communicates us the secret thought of the past, the present incessant work, and the future’s unknown.

Those so-called “luxury” books, which we often have the inclination to condemn, because they seem to be only accessible to few, do not hinder the popularization of the book which is produced in millions of copies, which crosses all the alleys and reaches all the houses, reflecting in its way the great errant work of the thought.

But a tradition of making beautiful book does exist, which aims at the same perfection once reached in painting and sculpture. This is the work of man to whom many wonderful artists have dedicated their lives. Among them was Tallone.

Tallone from Italy for many of you is just a name, while it means so much to me. I had admired his work even before I met him: his beautiful books, his immaculate typeface designed by himself. And I never thought that life would do me the great honor of having my books printed by him.

It happened one day, that I received an invitation from him. He lived near Turin, “presso Torino”, in Alpignano, and there we went, Matilde and I, by train. Yes, I knew where the house was, the printer had told me: the house is on this side of the railway. And we got there, but suddenly I felt disorientated; it seemed impossible, there was a steam locomotive with carriages, and the locomotive was smoking. I told Matilde: “We took the wrong way”.

No, sir! Among other things, Tallone was a collector of locomotives and he had one started so that the smoke would announce his house to me from afar.

I went through the bright room where there was people at work, the large workshop: an almost exact duplicate of Gutenberg’s printing press. The large tables, the metal letters set one by one, the shelves full of reams of wonderful Italian paper.

And then the conversation, the pleasantness of the wine – a white wine produced in the surroundings of Turin. But most of all it was his love for typography, his immense vocation as a printer, his absolute dedication to every page of his books, that illuminated him and beamed from his soul.

That European light went out, that humanist passed away, it is not long, leaving the book I wrote for him unfinished, “La Copa de Sangre”.

Bianca Tallone wrote me: “Alberto has left us, but I will finish the book and I will keep the Press alive; I feel responsible for this workshop and the great quality it is committed to”.

Tallone, among so many masters of typography, was the most rigorous, the most demanding. The slightest fault was a sin for him, a wound hat stood out from each printed line.

For instance, some of my books required six months of work, because a single accent was slanted in a different way than it should have, and he had to bring it back to its correct position.

The commitment, the decorum, the supreme beauty of his books are something to behold. He printed all the Italian classics and many great French poets, such as Ronsard. But it was in printing the most eminent Italian ones, from Dante to Machiavelli, from all the branches of Italian literature, that he achieved absolute excellence.

Here, then, I entrust you with a name which is, to me, unforgettable, and which shall enlighten us through his work.

PABLO NERUDA

Santiago, Chile, November 12, 1970

Interview with Alberto Tallone (1966).

Enrico Tallone (2021)

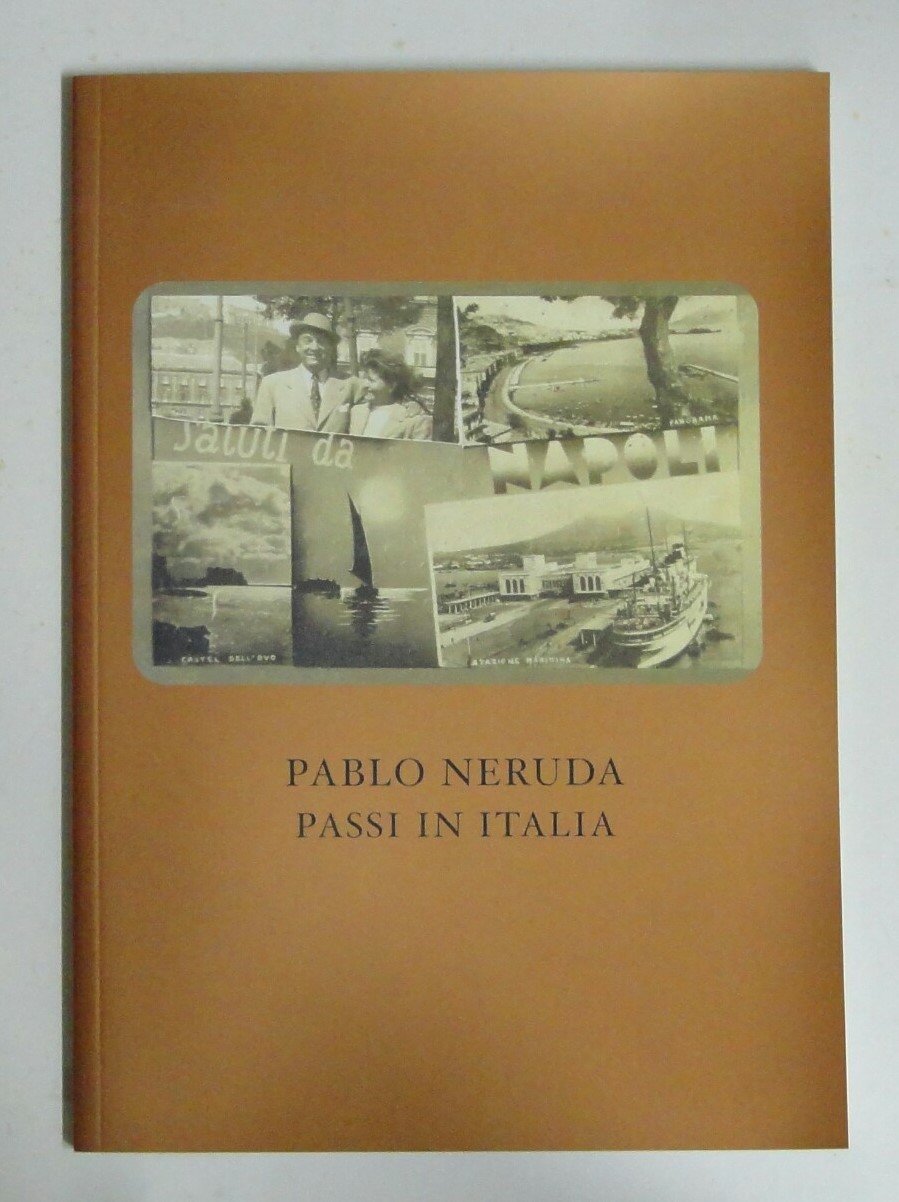

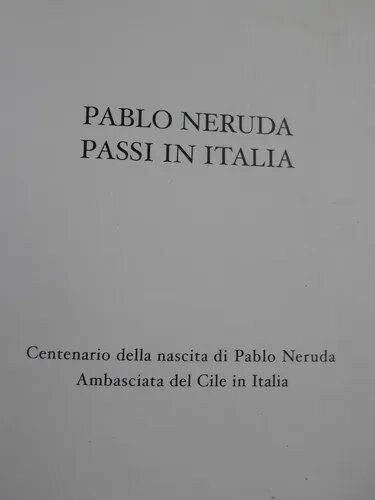

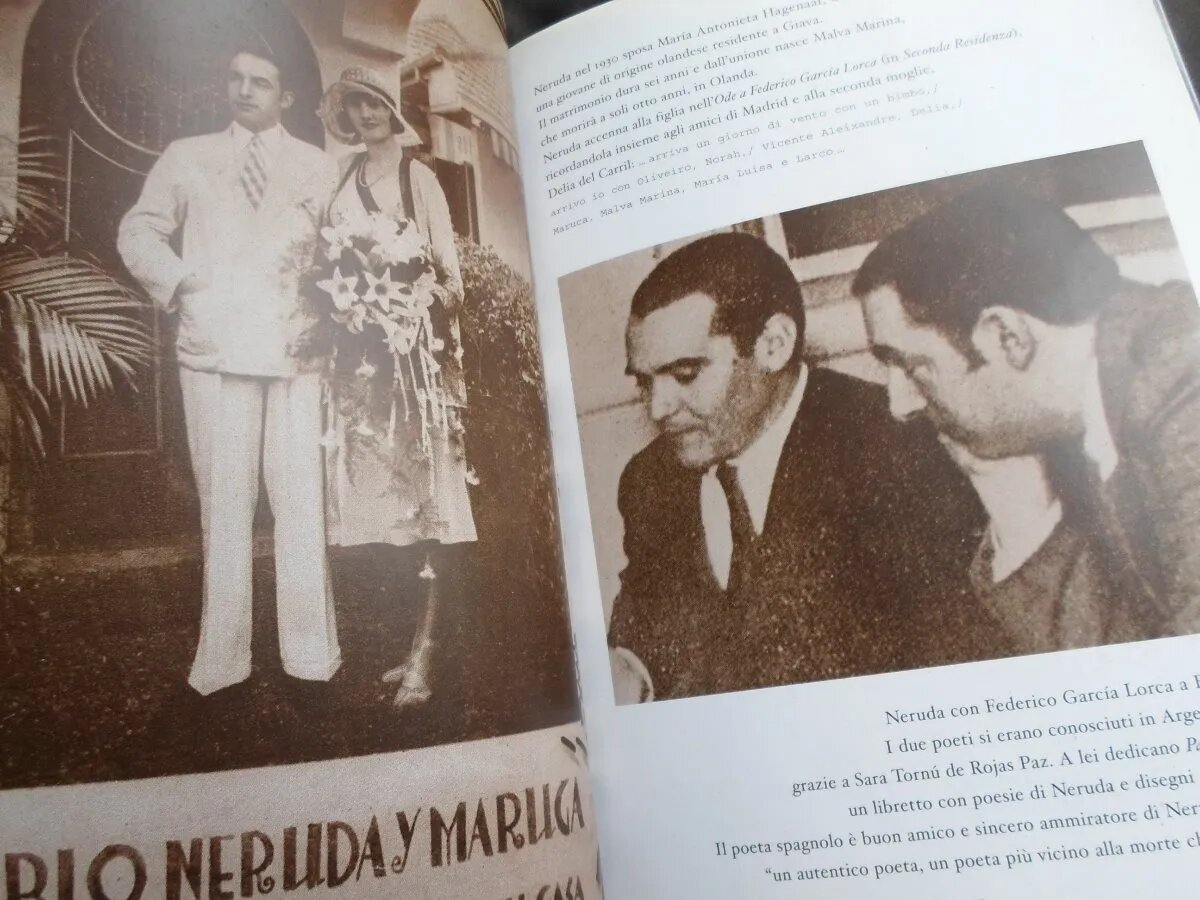

Libro Pablo Neruda. Passi in Italia.

Visit Enrico Tallone and his mother, Bianca Bianconi.

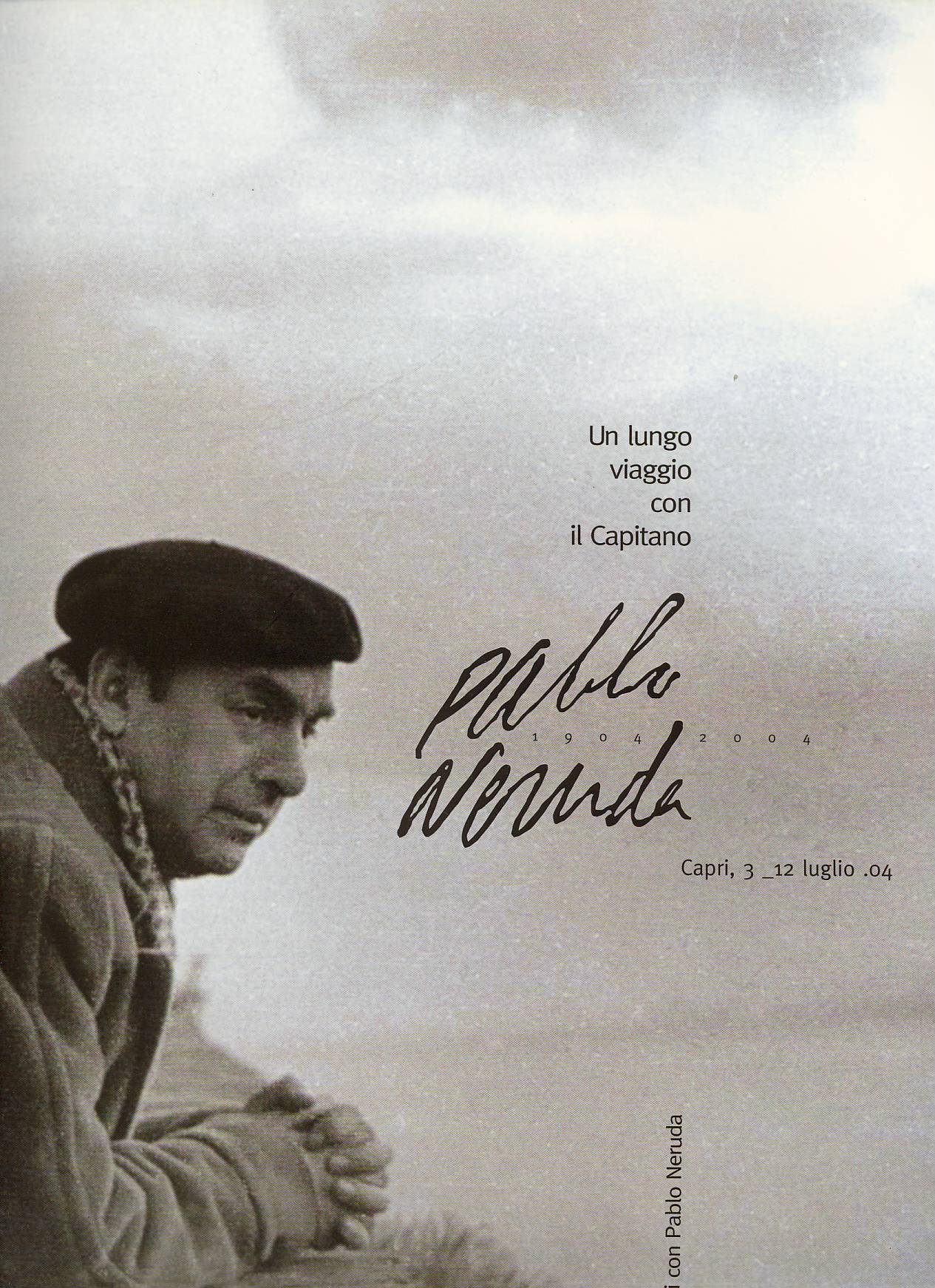

Un largo viaje con el Capitán. Capri, 2004.