Darío Oses

Journalist and Master in Latin American Studies (University of Chile). Director of the Pablo Neruda Foundation Library.

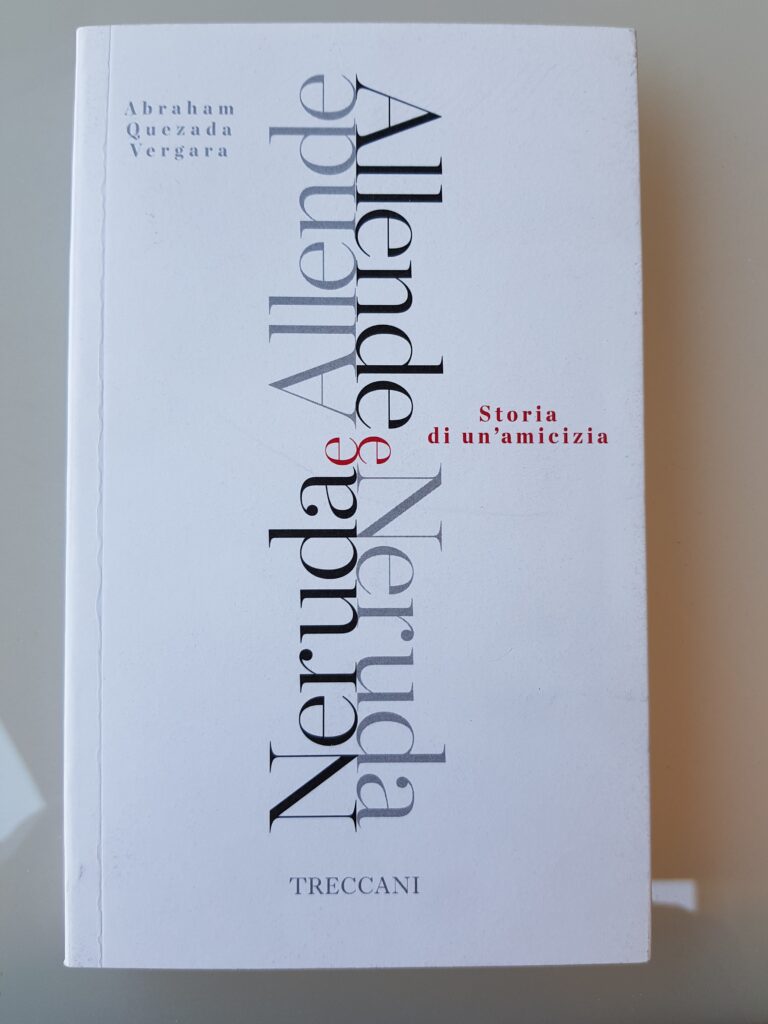

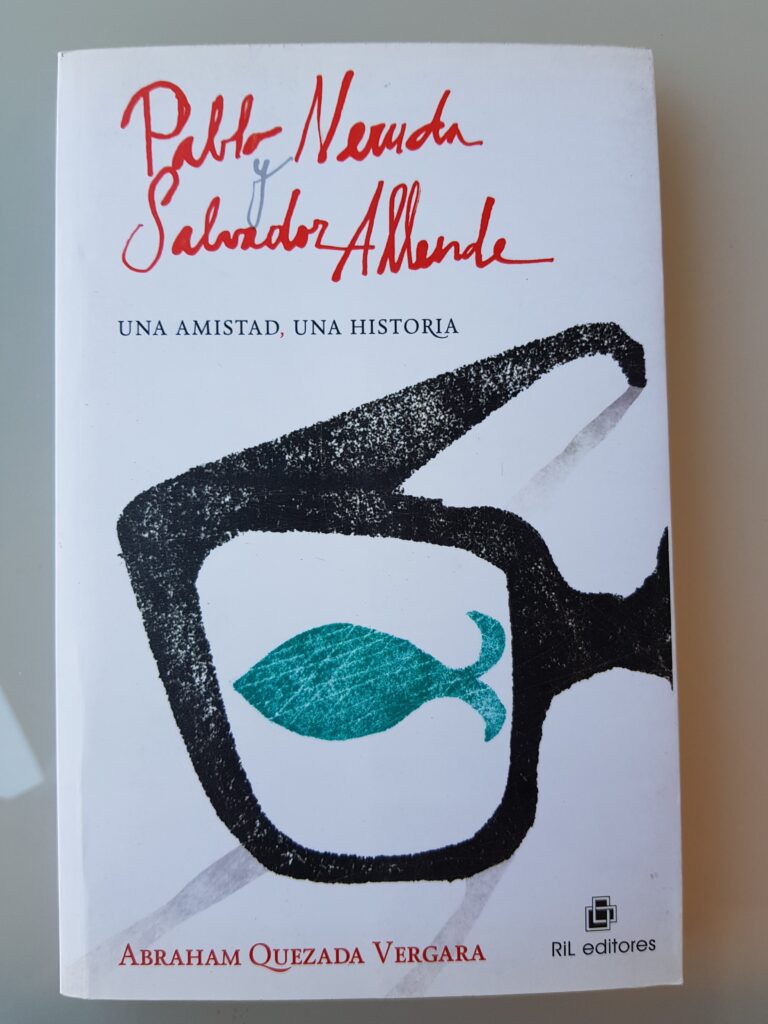

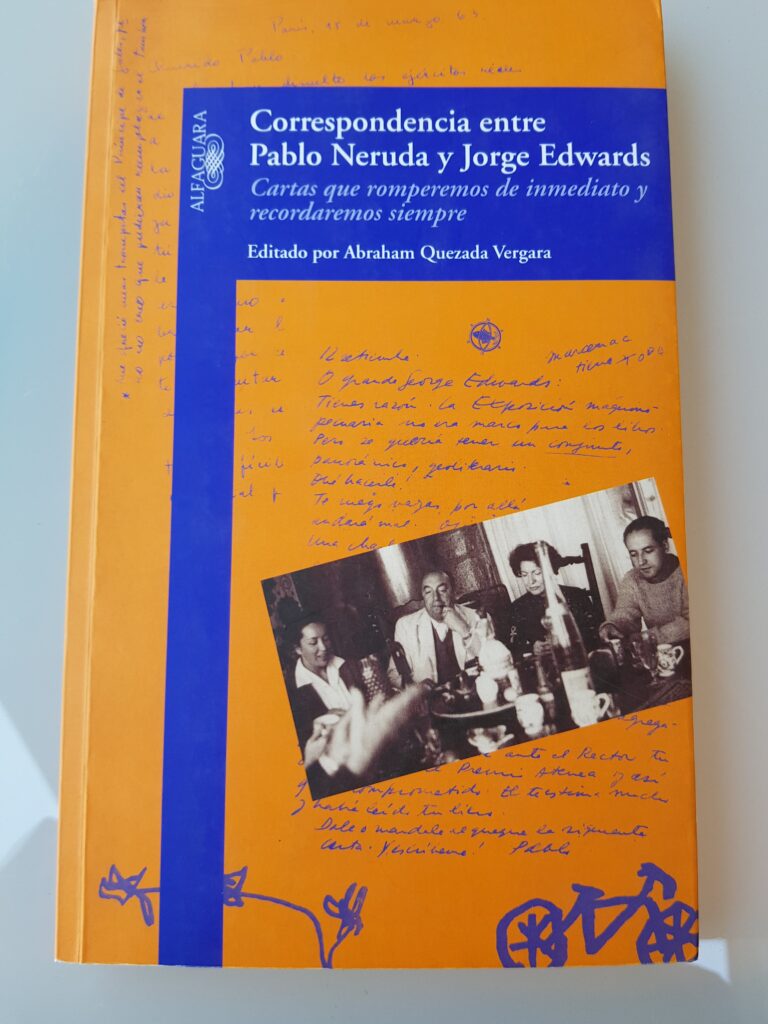

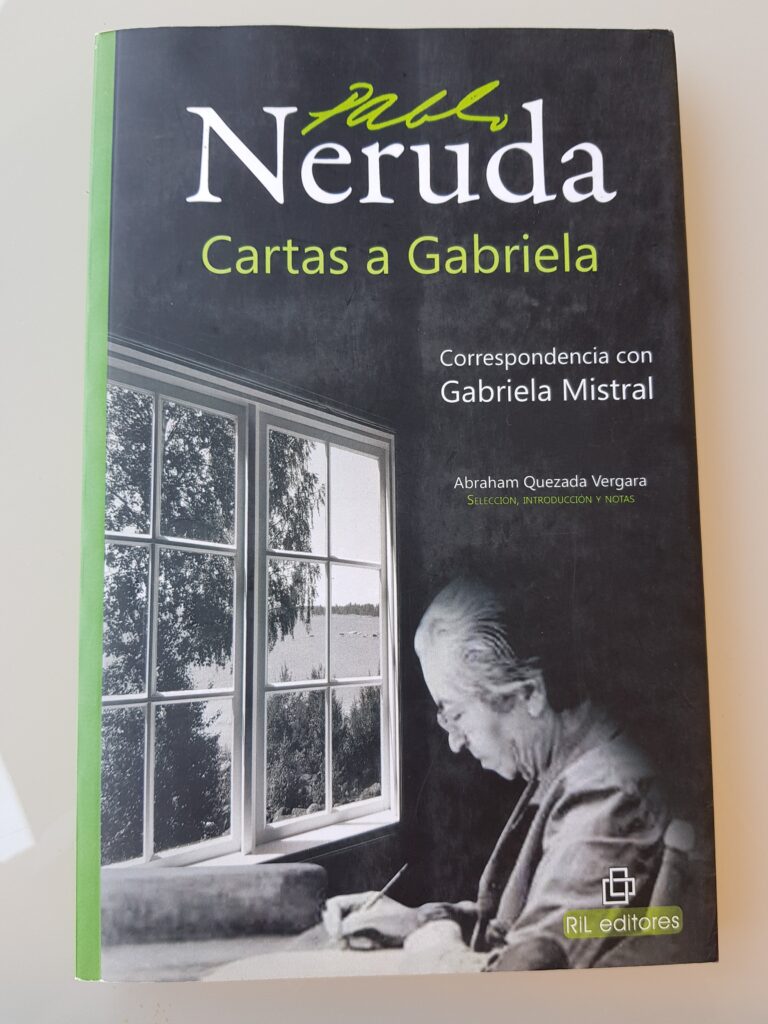

Writer and diplomat (Antofagasta, 1961). Professor of History and Geography graduated in Diplomacy. Master in International Relations and Doctor in American Studies. Researcher specialized in the biographical dimension of Pablo Neruda with important articles and books published both in national and foreign media. One of them, Allende – Neruda, a friendship, a story, with several editions in Spanish and translated into Italian by Treccani, one of the most prestigious publishers in Italy. A Chinese edition is also in preparation. A British publication has considered it as The world’s leading authority on the letters of Pablo Neruda (Cantalao N ° 1, London, Septembre, 2013).

Video transcription Abraham Quezada

Good afternoon, my friends. From the viceroyalty capital, from Lima, from Peru, I would like to extend an affectionate greeting to the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and the Tuscan Bibliographic Society of Italy, who have organized this magnificent exhibition, the first Chilean-Italian virtual exhibition “Pablo Neruda: 50 years Nobel Prize in Literature 1971-2021 “. And in that sense, I take the opportunity to greet and also thank the institutions that have contributed to this: the General Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile stands out, the place where I work, and in Italy, the Library from the Ignazio Cerio Caprense Center, a place that I visited a few years ago.

Undoubtedly, this exhibition is a relevant, extraordinary and, I would say, even endearing exhibition of Neruda, because it shows us the bibliophile Neruda, one of his great passions. Neruda and his collections in Chile and, finally, Neruda in Italy. These three spaces are spaces much loved by the poet and that he developed to the full.

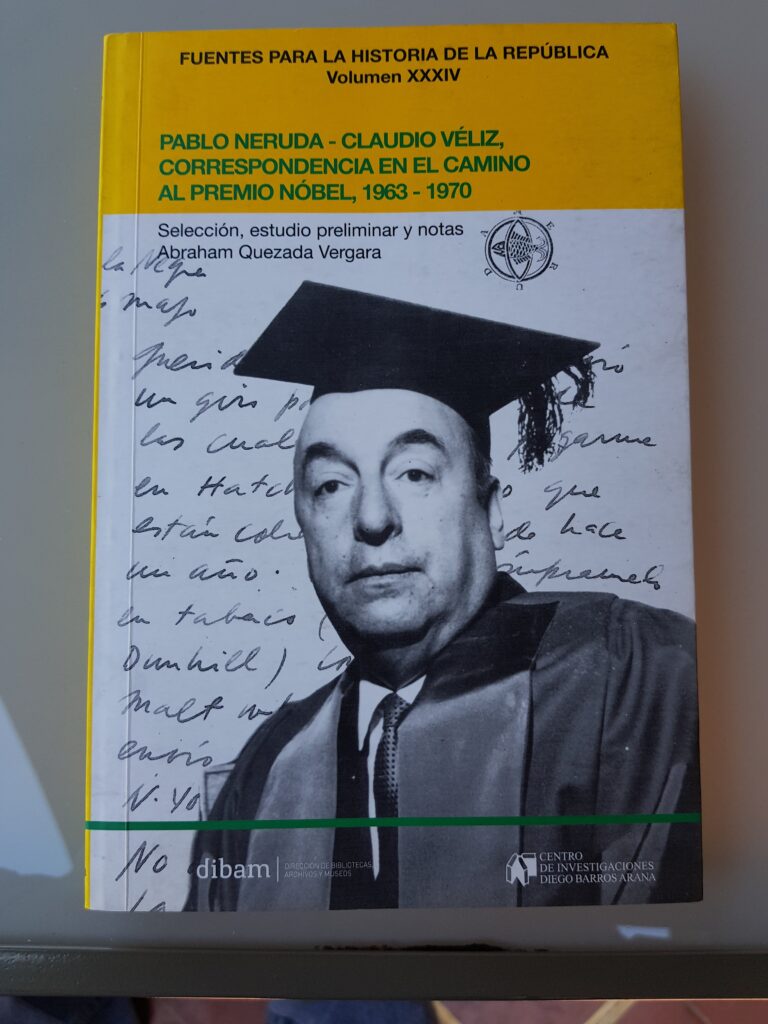

In his role as a bibliophile, for example, I just want to tell you two anecdotes that I had the privilege of bringing to light in some of my published works. One of them is the intense correspondence that the poet carries out with the Chilean academic Claudio Veliz so he can get for him in London an old and very valuable book entitled Travels whose author is Amasa Delano, where in August of 1963 he tells him that he is willing to pay “whatever they ask of him” and in November of that same year, that is to say, a few months later, he adds: “I burn with the desire to see and feel that book.” This was an acquisition that ultimately came to fruition and the poet received the book. When he received it, he held a reception in Isla Negra with all his friends and he was immensely happy.

Another similar anecdote is his desperate and insistent attempts, through his Peruvian friends, to acquire an original copy of Flora Tristán’s book, Peregrinaciones de una Paria, that book from 1838, in its original edition, in French. There were other editions in Chile. Even Ercilla Press, in the 1940s, had published one edition and there were another two more published that the poet could perfectly read. But no, he wanted the original French edition, and why did he want it so much? Because apart from the taste of the old book, of smelling, touching, feeling, as he says in one of his letters, Flora Tristán recounted her passage through Valparaíso and the lies and anecdotes that were circulating in our historic port at that time. Therefore, the poet wanted it in its original edition.

Therefore, this documentary contribution that you are making, with so much care, with so much love, comes, I believe, to justly celebrate Neruda’s intellectual effort and his love for books, while giving an account of his intense poetic world where there is still much to discover.

Luckily for us researchers and scholars, the Neruda`s universe is an expanding universe and the contribution that the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles is making of exposing it very professionally and sharing it, which is the ultimate goal that all people and institutions should have, who are dedicated to it, it is a truly remarkable effort.

If the poet were alive, without a doubt, he would be happy with this initiative, hopefully it will have a second, a third, a fourth and successive versions from now on.

To finish, just a reflection on Neruda and the Nobel Prize.

You well know that Neruda’s Nobel Prize was the second Nobel Prize for Chile and the third for Latin America, after Mistral’s in 1945 and Miguel Ángel Asturias’s in 1967. But Neruda had been a candidate for this recognition since late from the 40s.

In 1964, the poet was deeply moved when he learned of the resignation of the prize that Jean Paul Sartre had made. In the letter that this French philosopher sends to Stockholm, among other arguments, he says “I am not worthy of winning this award until it is given to poets like Neruda.”

Finally, the poet got it. And why did you get it? He got it, without a doubt, because of his talent and his career. But he also got it because of his persistence, because he was tenacious, and he believed and was convinced that he deserved it. So it is with these types of samples, I believe that they account for such a rich expanding universe, I repeat, that Neruda, luckily for all of us, continues to offer us these joys.

Thank you very much for the work done, I send you a warm greeting from Lima. Thank you.

Pablo Neruda, socio número 80 de la Sociedad de Bibliófilos Chilenos, en la cual participó desde sus inicios, fue un bibliófilo en todo el sentido de la palabra. En su biblioteca personal, había más de 11.500 libros, además de cartas, manuscritos de gran valor histórico y cultural, que actualmente se conservan tanto en la Fundación Pablo Neruda, como en la Universidad de Chile, su Alma Mater, donde estudió Pedagogía en Francés y a la cual donó parte de sus colecciones en 1954.

Desde muy joven, fue un ávido lector y buscador de obras literarias antiguas, únicas, raras y valiosas, pasión que se vio facilitada debido a sus numerosos viajes y estadías en diferentes países.

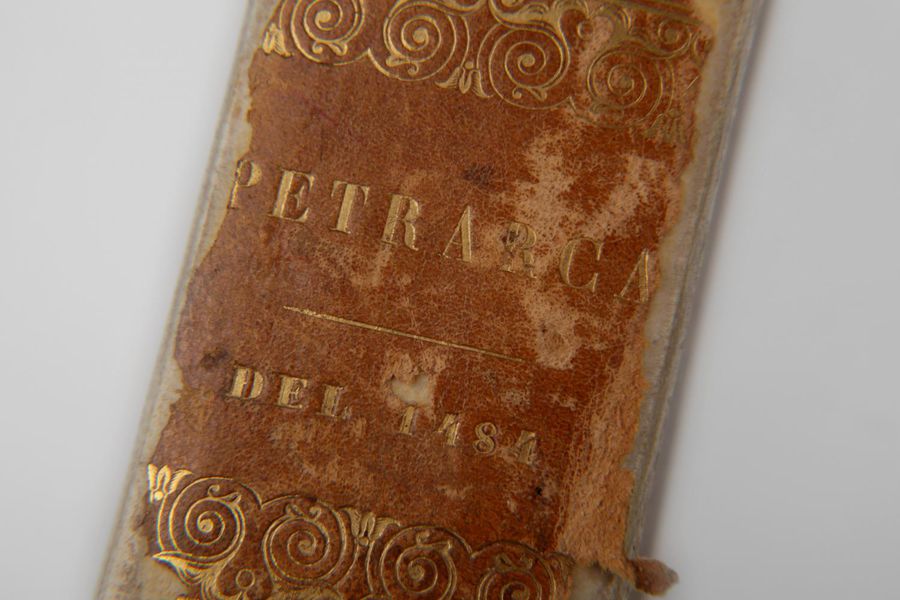

De literatura chilena, poseía un ejemplar de La Araucana, de 1632 (la primera edición, es de 1569). Como sabemos, Neruda además sentía especial predilección por Francia e Italia. Con respecto a obras italianas, tenía una copia de Orlando Furioso, de Ludovico Ariosto, de 1561 (la 1° edición es de 1532) y un ejemplar de La Divina Comedia de Dante Alighieri, del año 1529. Así también, una edición de Triunfos de Petrarca, edición de 1484 (1° ed. original: entre 1351 y 1374. Editio prínceps: Venecia, Vindelino da Spira, 1470). De obras francesas, poseía la Enciclopedia de Diderot y D’Alembert, de 1751. También era propietario de las pruebas de imprenta de Los trabajadores del mar (1866), de Víctor Hugo, con correcciones en los bordes, escritas de puño y letra por su autor.

En referencia a España, país que también era uno de sus predilectos, poseía una edición del Quijote de la Mancha, de 1617. Además, de literatura norteamericana, era dueño de las Obras Completas de Edgar Allan Poe, publicadas en New York, en 1895.

Poco a poco, Neruda formó su amada biblioteca con especial cuidado y dedicación. Era exquisito en los detalles de edición, papel, costuras. Le gustaban los tirajes cortos, como Los Versos del Capitán, con solo 44 ejemplares, porque concebía sus libros en términos de colección. Así también, varios de sus libros unen literatura y pintura, al presentar poemas con obras de Mario Toral de Chile, Guayasamín de Ecuador y Picasso de España. En definitiva, como todo bibliófilo refinado, atesoraba los libros tanto por el valor de las ideas transmitidas, como por la forma. En este sentido, consideraba al libro como un objeto de arte en sí mismo.

Colección Neruda. Archivo Central Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

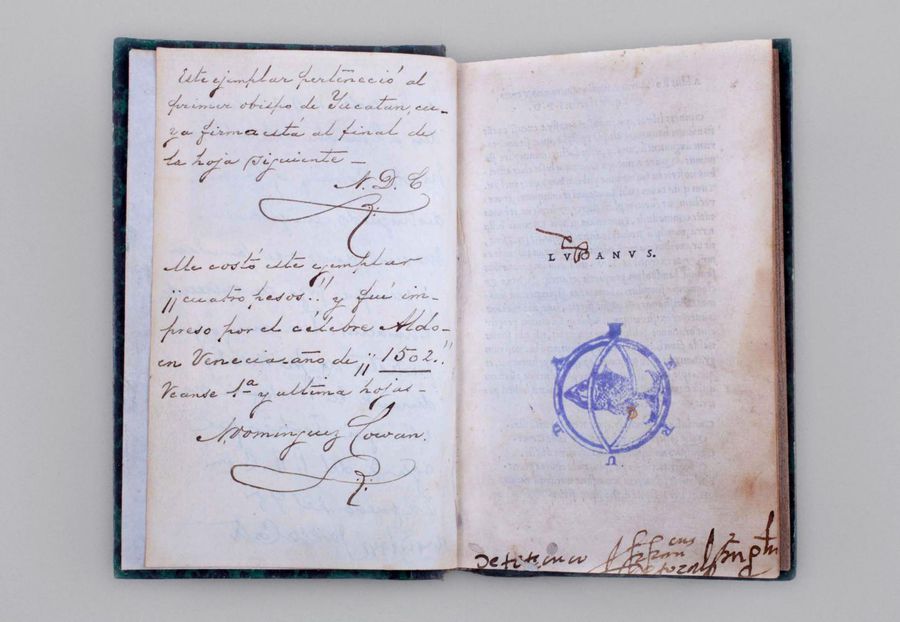

Libro incunable. “La palabra incunable (del latín incunabulae, en la cuna) se utiliza para designar a todos los libros impresos en Europa occidental desde que el orfebre alemán Johannes Gensfleisch -más conocido como Johannes Zum Gutemberg (1400-1468)- inventa la imprenta con tipos móviles en Maguncia el año 1440, inspirado en las prensas utilizadas para exprimir uvas en el proceso de elaboración del vino. La denominación “incunable” rige conceptualmente hasta 1501, fecha en que esta tecnología se masificó. Para entonces, en cientos de ciudades europeas había prensas dedicadas a reproducir textos.”

Colección Neruda. Archivo Central Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

“Pharsalia (también conocida como Bellum civile), es un poema inacabado en diez cantos, el cual narra la guerra civil entre Julio César y Pompeyo, corresponde a un texto escrito en latín por el célebre poeta romano Marco Anneo Lucano (39- 65 d.c). Pertenece a la colección de 5.107 volúmenes donados por el poeta Pablo Neruda el año 1954 a la Universidad de Chile.

Se trata de una epopeya concebida en orden cronológico y considerada un clásico dentro del canon de la literatura antigua.

El libro fue compuesto en el siglo XVI por la imprenta del humanista e impresor italiano Aldus Manutius (1450-1515), quien fuera reconocido como el más grande tipógrafo de su tiempo, por haber dado forma a criterios importantes de edición, tales como la puntuación, la invención del punto y coma, de los caracteres cursivos, la numeración de las páginas y el formato en octavo.”

Colección Neruda. Archivo Central Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

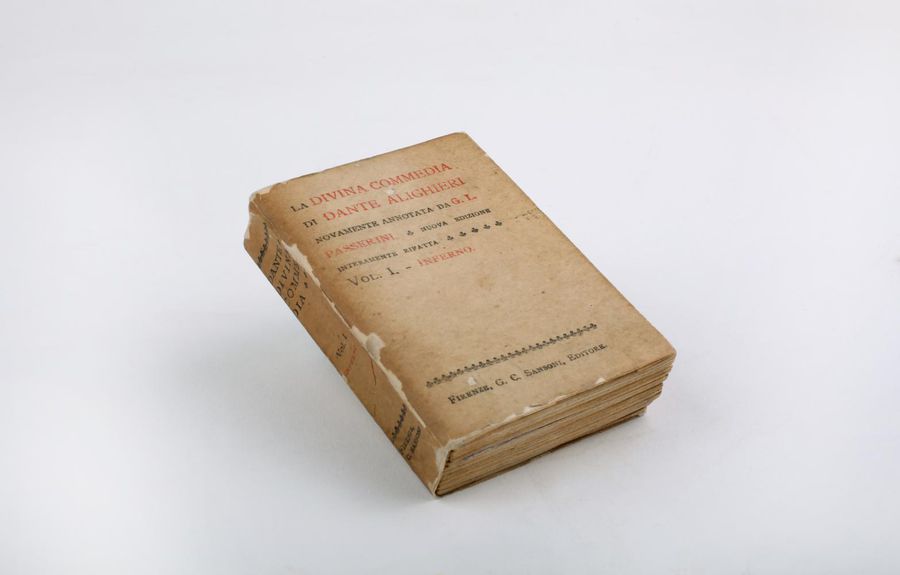

“Edición en pequeño formato de la obra del poeta Dante Alighieri (c. 1265-1321), publicada en italiano, en la ciudad de Florencia el año 1915. Fue compuesta por G. C Sansoni Editore. Incluye antecedentes biográficos del autor y anotaciones página a página. Pertenece a la Colección donada en 1954 por Pablo Neruda a la Universidad de Chile, conjunto que fue declarado Monumento Histórico Nacional en 2009.”

![Víctor Hugo, Les travailleurs de la mer [maquette], Librairie Internationale A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et C. Editeurs, Paris, 1866, 2 vólumenes.](https://pabloneruda.bibliofilos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/thumb-3.jpg)

Colección Neruda. Archivo Central Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

“Pruebas de imprenta de la primera edición del libro Les travailleurs de la mer, texto escrito por Víctor Hugo (1802- 1885), poeta, novelista y dramaturgo francés considerado como uno de los mayores exponentes literarios del siglo XIX. “

Colección Neruda. Archivo Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

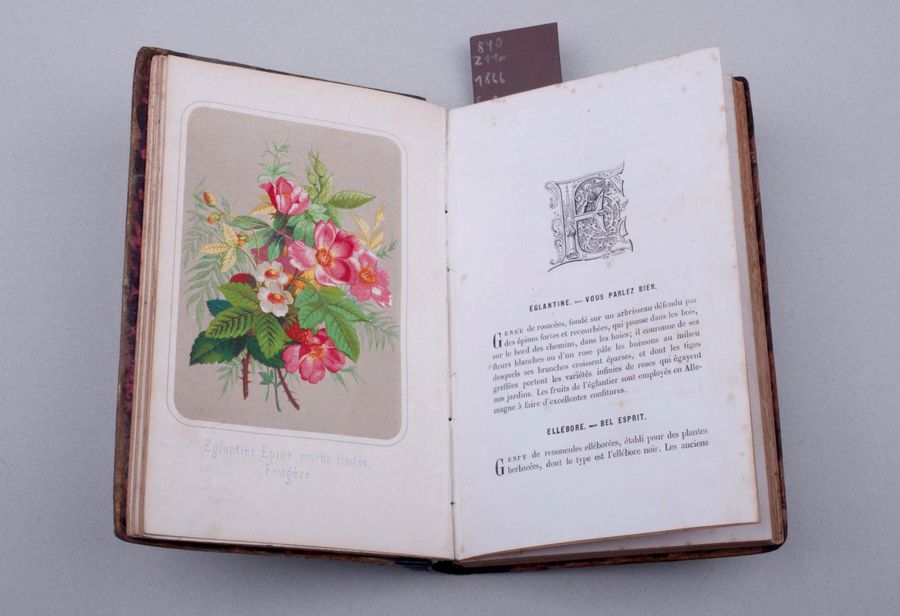

Nouveau langage des fleurs es un libro único en Chile. “El texto, sin autor preciso, tiene tres objetivos: identificar conceptualmente el lenguaje existente de manera implícita en cada una de las flores ordenadas por tipos y nomenclaturas precisas; interpretar el valor simbólico de las mismas; y ejemplificar el uso literario, novelesco y poético que las flores han tenido, considerando el trabajo de múltiples escritores europeos, entre los que se encuentra el eminente Honoré de Balzac. Al final del libro encontramos poesías y narraciones al respecto.”

Colección Neruda. Archivo Central Andrés Bello, Universidad de Chile.

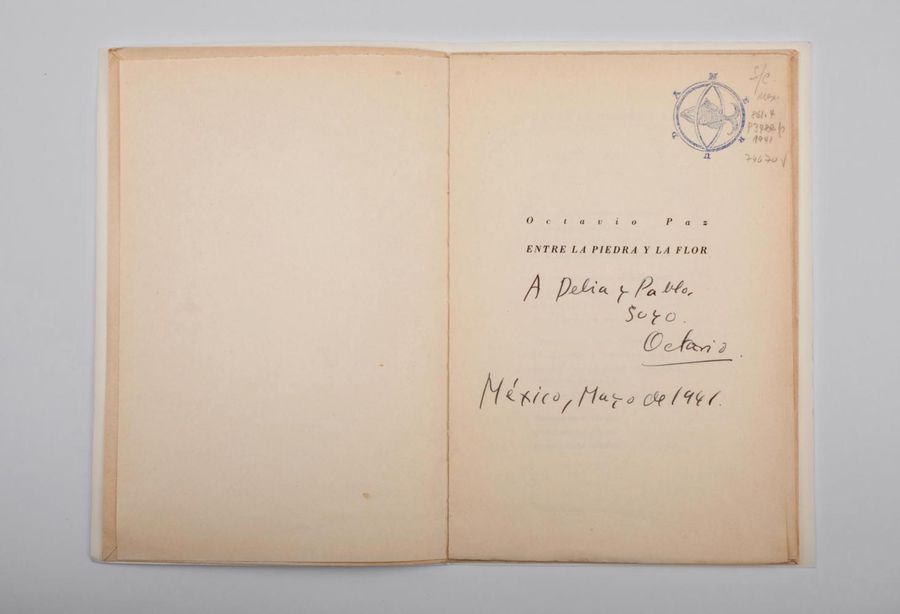

“Libro editado por el sello mexicano Nueva Voz en 1941, dedicado por su autor a Pablo Neruda y a su entonces esposa Delia del Carril el mismo año de la publicación. Octavio Paz (1914-1998), poeta, ensayista, traductor y destacado intelectual mexicano trabó amistad con Pablo Neruda en el contexto del II Congreso Internacional de Escritores en Defensa de la Cultura, España, 1937.” Más tarde, en 1990, Octavio Paz obtuvo el Premio Nobel de Literatura.

Investigation: Norma Alcamán

Pablo Neruda, 80th member of the Chilean Bibliophile Society, in which he participated from the beginning, was a bibliophile in every sense of the word. In his personal library, there were more than 11,500 books, in addition to letters, manuscripts of great historical and cultural value, which are currently preserved both at the Pablo Neruda Foundation and at the University of Chile, his Alma Mater, where he studied French Pedagogy. and to which he donated part of his collections in 1954.

From a very young age, he was an avid reader and seeker of ancient, unique, rare and valuable literary works, a passion that was facilitated by his many trips and stays in different countries.

Of Chilean literature, he owned a copy of La Araucana, from 1632 (the first edition is from 1569). As we know, Neruda also had a special predilection for France and Italy. With regard to Italian works, he had a copy of Orlando Furioso, by Ludovico Ariosto, from 1561 (the 1st edition is from 1532) and a copy of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, from the year 1529. Also, an edition of Triumphs de Petrarca, edition of 1484 (1st ed. original: between 1351 and 1374. Editio princes: Venice, Vindelino da Spira, 1470). Of French works, he owned the Encyclopedia of Diderot and D’Alembert, of 1751. He also owned the proofs of the workers of the sea (1866), by Victor Hugo, with corrections around the edges, handwritten by its author.

With reference to Spain, a country that was also one of his favorites, he had an edition of Don Quixote de la Mancha, from 1617. In addition, of North American literature, he owned the Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, published in New York in 1895.

Little by little, Neruda built his beloved library with special care and dedication. It was exquisite in the details of editing, paper, stitching. He liked short runs, such as Los Versos del Capitán, with only 44 copies, because he conceived of his books in terms of collections. Also, several of his books unite literature and painting, presenting poems with works by Mario Toral from Chile, Guayasamín from Ecuador and Picasso from Spain. Ultimately, like any refined bibliophile, he treasured books as much for the value of the ideas conveyed as for the form. In this sense, he considered the book as an art object in itself.