Pablo Neruda Foundation

Darío Oses

Journalist and Master in Latin American Studies (University of Chile). Director of the Pablo Neruda Foundation Library.

The Society of Chilean Bibliophiles, together with the Società Bibliografica Toscana, from Italy, are pleased to invite you to visit this virtual exhibition.

We thank, the Pablo Neruda Foundation in Chile, the Cultural Heritage Corporation, and the General Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In Italy we thank to Alberto Tallone Editore and the Ignazio Cerio Capri Center Library.

The historian Ricardo Couyoumdjian, President of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles, greets you and welcomes you.

The lawyer Paolo Tiezzi Mazzoni della Stella Maestri, President of the la Società Bibliografica Toscana, greets you and welcomes you.

The Society of Chilean Bibliophiles, founded in 1945, aims to preserve the “culture of the book”. For this reason, it brings together collectors, promotes research and publishes old editions of Chilean heritage value in the fields of Literature, Law, History, Arts and Sciences.

On August 12, 2019, our Chilean-Italian international phase began, both for the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and for the Società Bibliografica Toscana. That day, we signed an International Cultural Cooperation Protocol, with the aim of carrying out together various exhibition projects, book publications and other activities of common interest to the public.

This year 2020, to celebrate 75 years of activity, we honour our most outstanding member: Pablo Neruda, who on December 10, 1971 received the Nobel Prize for Literature. With this inspiration, we have prepared, together with the Italian friends of the Società Bibliografica Toscana, our first virtual exhibition, which consists of the following parts:

(I) Neruda Bibliophile

(II) Neruda and the collectors in Chile

(III) Neruda in Italy

In all three, we will find texts little known by the public, which will provide us with new points of view about their creative richness that, in itself, configures a poetic world where there is still much to discover.

All of us who work on this project are certain that culture is a bridge that unites countries. In this particular case, the great poetic work of Pablo Neruda - recognized and valued throughout the world - is a bridge that unites Chile and Italy, two countries that are geographically far apart, but close due to our common Latin base, by our great affinity and solid friendship.

Due to the pandemic, we are offering you a virtual exhibition that, we hope, will be a beautiful bibliophile and poetic experience for you.

Norma Alcaman Riffo

Master in Literature and Diploma in Cultural Administration. Writer.

Director of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and Member of the Società Bibliografica Toscana, in Italy. Director of this virtual exhibition.

Enrique Inda, Architect. Director de la Society Of Chileans Bibliophiles y Vice President of the Foundation Pablo Neruda. Collector of Neruda`s work.

Ignacio Swett, Civil Engineer. Treasurer of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles. Collector of Neruda`s work.

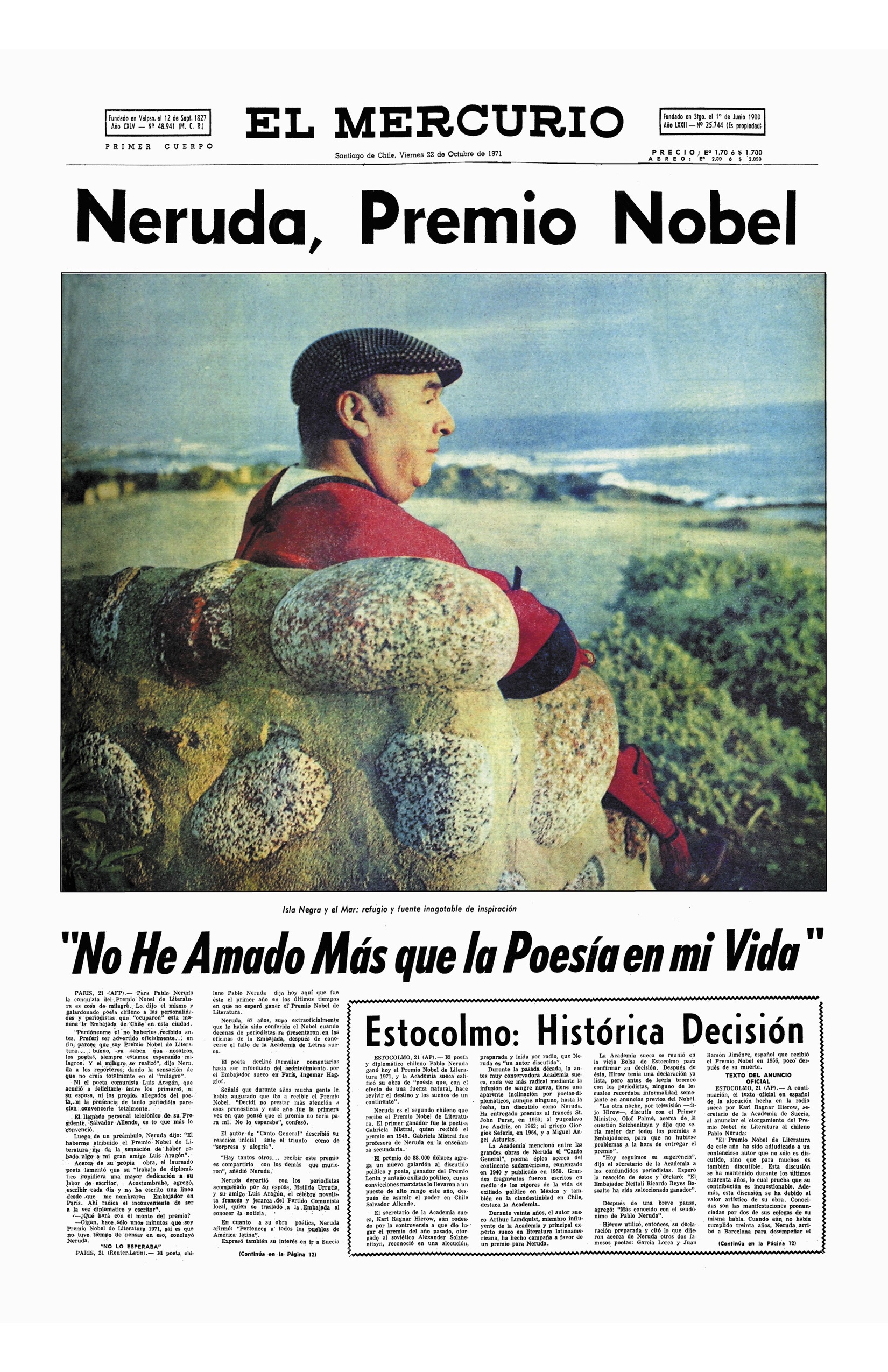

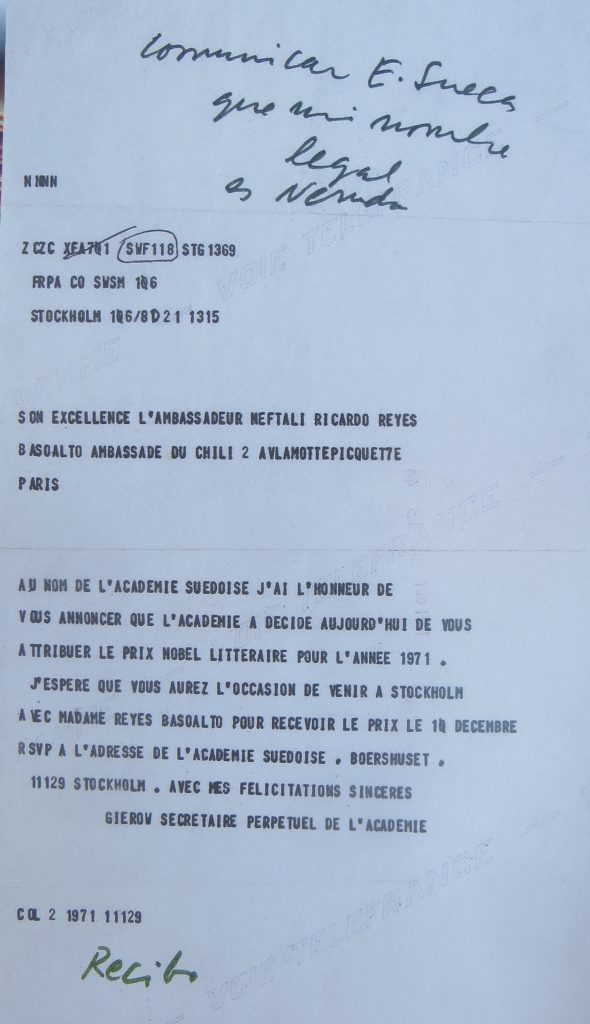

Cover of the newspaper El Mercurio, the most important in the country, with the news of Pablo Neruda, winner of the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. Santiago de Chile, Friday October 22, 1971.

News from El Mercurio, referring to the 75 years of the Chilean Bibliophile Society (1945-2020). Wednesday, August 12, 2020, page A-7.

Journalist and Master in Latin American Studies (University of Chile). Director of the Pablo Neruda Foundation Library.

Writer and diplomat (Antofagasta, 1961). Professor of History and Geography graduated in Diplomacy. Master in International Relations and Doctor in American Studies. Researcher specialized in the biographical dimension of Pablo Neruda with important articles and books published both in national and foreign media. One of them, Allende – Neruda, a friendship, a story, with several editions in Spanish and translated into Italian by Treccani, one of the most prestigious publishers in Italy. A Chinese edition is also in preparation. A British publication has considered it as The world’s leading authority on the letters of Pablo Neruda (Cantalao N ° 1, London, Septembre, 2013).

Video transcription Abraham Quezada

Good afternoon, my friends. From the viceroyalty capital, from Lima, from Peru, I would like to extend an affectionate greeting to the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and the Tuscan Bibliographic Society of Italy, who have organized this magnificent exhibition, the first Chilean-Italian virtual exhibition “Pablo Neruda: 50 years Nobel Prize in Literature 1971-2021 “. And in that sense, I take the opportunity to greet and also thank the institutions that have contributed to this: the General Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile stands out, the place where I work, and in Italy, the Library from the Ignazio Cerio Caprense Center, a place that I visited a few years ago.

Undoubtedly, this exhibition is a relevant, extraordinary and, I would say, even endearing exhibition of Neruda, because it shows us the bibliophile Neruda, one of his great passions. Neruda and his collections in Chile and, finally, Neruda in Italy. These three spaces are spaces much loved by the poet and that he developed to the full.

In his role as a bibliophile, for example, I just want to tell you two anecdotes that I had the privilege of bringing to light in some of my published works. One of them is the intense correspondence that the poet carries out with the Chilean academic Claudio Veliz so he can get for him in London an old and very valuable book entitled Travels whose author is Amasa Delano, where in August of 1963 he tells him that he is willing to pay “whatever they ask of him” and in November of that same year, that is to say, a few months later, he adds: “I burn with the desire to see and feel that book.” This was an acquisition that ultimately came to fruition and the poet received the book. When he received it, he held a reception in Isla Negra with all his friends and he was immensely happy.

Another similar anecdote is his desperate and insistent attempts, through his Peruvian friends, to acquire an original copy of Flora Tristán’s book, Peregrinaciones de una Paria, that book from 1838, in its original edition, in French. There were other editions in Chile. Even Ercilla Press, in the 1940s, had published one edition and there were another two more published that the poet could perfectly read. But no, he wanted the original French edition, and why did he want it so much? Because apart from the taste of the old book, of smelling, touching, feeling, as he says in one of his letters, Flora Tristán recounted her passage through Valparaíso and the lies and anecdotes that were circulating in our historic port at that time. Therefore, the poet wanted it in its original edition.

Therefore, this documentary contribution that you are making, with so much care, with so much love, comes, I believe, to justly celebrate Neruda’s intellectual effort and his love for books, while giving an account of his intense poetic world where there is still much to discover.

Luckily for us researchers and scholars, the Neruda`s universe is an expanding universe and the contribution that the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles is making of exposing it very professionally and sharing it, which is the ultimate goal that all people and institutions should have, who are dedicated to it, it is a truly remarkable effort.

If the poet were alive, without a doubt, he would be happy with this initiative, hopefully it will have a second, a third, a fourth and successive versions from now on.

To finish, just a reflection on Neruda and the Nobel Prize.

You well know that Neruda’s Nobel Prize was the second Nobel Prize for Chile and the third for Latin America, after Mistral’s in 1945 and Miguel Ángel Asturias’s in 1967. But Neruda had been a candidate for this recognition since late from the 40s.

In 1964, the poet was deeply moved when he learned of the resignation of the prize that Jean Paul Sartre had made. In the letter that this French philosopher sends to Stockholm, among other arguments, he says “I am not worthy of winning this award until it is given to poets like Neruda.”

Finally, the poet got it. And why did you get it? He got it, without a doubt, because of his talent and his career. But he also got it because of his persistence, because he was tenacious, and he believed and was convinced that he deserved it. So it is with these types of samples, I believe that they account for such a rich expanding universe, I repeat, that Neruda, luckily for all of us, continues to offer us these joys.

Thank you very much for the work done, I send you a warm greeting from Lima. Thank you.

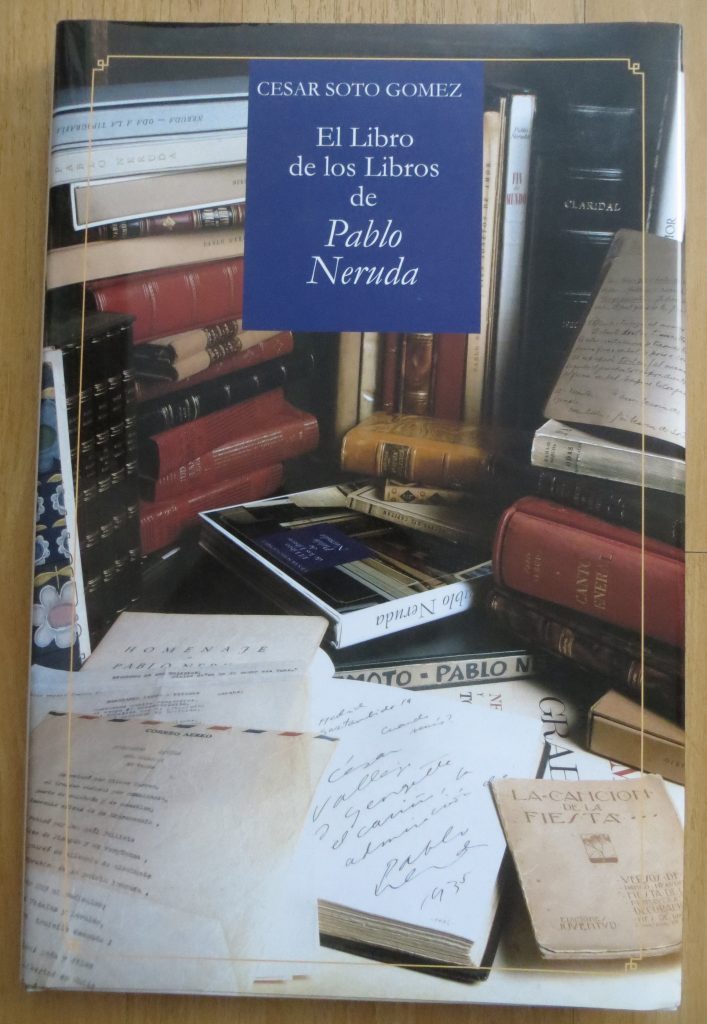

Pablo Neruda, socio número 80 de la Sociedad de Bibliófilos Chilenos, en la cual participó desde sus inicios, fue un bibliófilo en todo el sentido de la palabra. En su biblioteca personal, había más de 11.500 libros, además de cartas, manuscritos de gran valor histórico y cultural, que actualmente se conservan tanto en la Fundación Pablo Neruda, como en la Universidad de Chile, su Alma Mater, donde estudió Pedagogía en Francés y a la cual donó parte de sus colecciones en 1954.

Desde muy joven, fue un ávido lector y buscador de obras literarias antiguas, únicas, raras y valiosas, pasión que se vio facilitada debido a sus numerosos viajes y estadías en diferentes países.

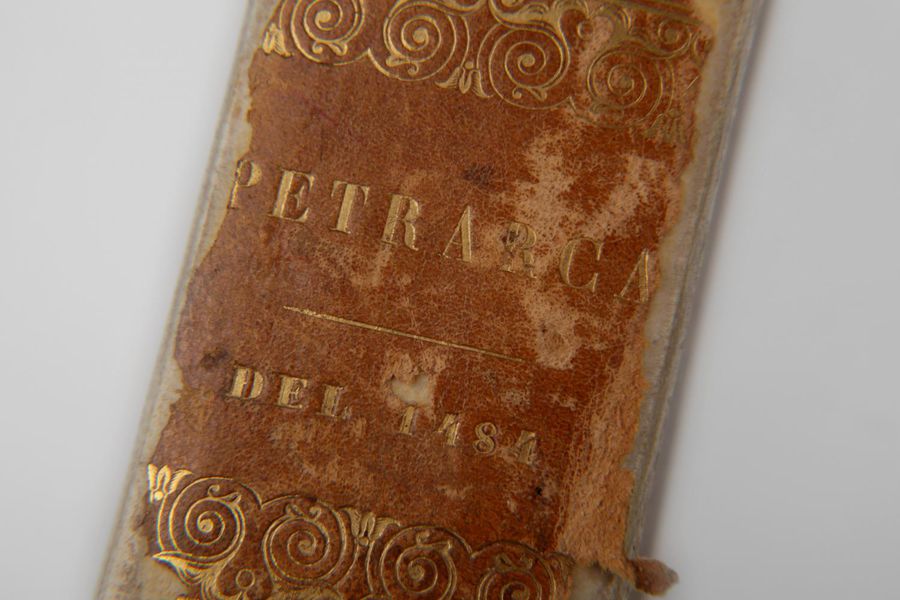

De literatura chilena, poseía un ejemplar de La Araucana, de 1632 (la primera edición, es de 1569). Como sabemos, Neruda además sentía especial predilección por Francia e Italia. Con respecto a obras italianas, tenía una copia de Orlando Furioso, de Ludovico Ariosto, de 1561 (la 1° edición es de 1532) y un ejemplar de La Divina Comedia de Dante Alighieri, del año 1529. Así también, una edición de Triunfos de Petrarca, edición de 1484 (1° ed. original: entre 1351 y 1374. Editio prínceps: Venecia, Vindelino da Spira, 1470). De obras francesas, poseía la Enciclopedia de Diderot y D’Alembert, de 1751. También era propietario de las pruebas de imprenta de Los trabajadores del mar (1866), de Víctor Hugo, con correcciones en los bordes, escritas de puño y letra por su autor.

En referencia a España, país que también era uno de sus predilectos, poseía una edición del Quijote de la Mancha, de 1617. Además, de literatura norteamericana, era dueño de las Obras Completas de Edgar Allan Poe, publicadas en New York, en 1895.

Poco a poco, Neruda formó su amada biblioteca con especial cuidado y dedicación. Era exquisito en los detalles de edición, papel, costuras. Le gustaban los tirajes cortos, como Los Versos del Capitán, con solo 44 ejemplares, porque concebía sus libros en términos de colección. Así también, varios de sus libros unen literatura y pintura, al presentar poemas con obras de Mario Toral de Chile, Guayasamín de Ecuador y Picasso de España. En definitiva, como todo bibliófilo refinado, atesoraba los libros tanto por el valor de las ideas transmitidas, como por la forma. En este sentido, consideraba al libro como un objeto de arte en sí mismo.

Libro incunable. “La palabra incunable (del latín incunabulae, en la cuna) se utiliza para designar a todos los libros impresos en Europa occidental desde que el orfebre alemán Johannes Gensfleisch -más conocido como Johannes Zum Gutemberg (1400-1468)- inventa la imprenta con tipos móviles en Maguncia el año 1440, inspirado en las prensas utilizadas para exprimir uvas en el proceso de elaboración del vino. La denominación “incunable” rige conceptualmente hasta 1501, fecha en que esta tecnología se masificó. Para entonces, en cientos de ciudades europeas había prensas dedicadas a reproducir textos.”

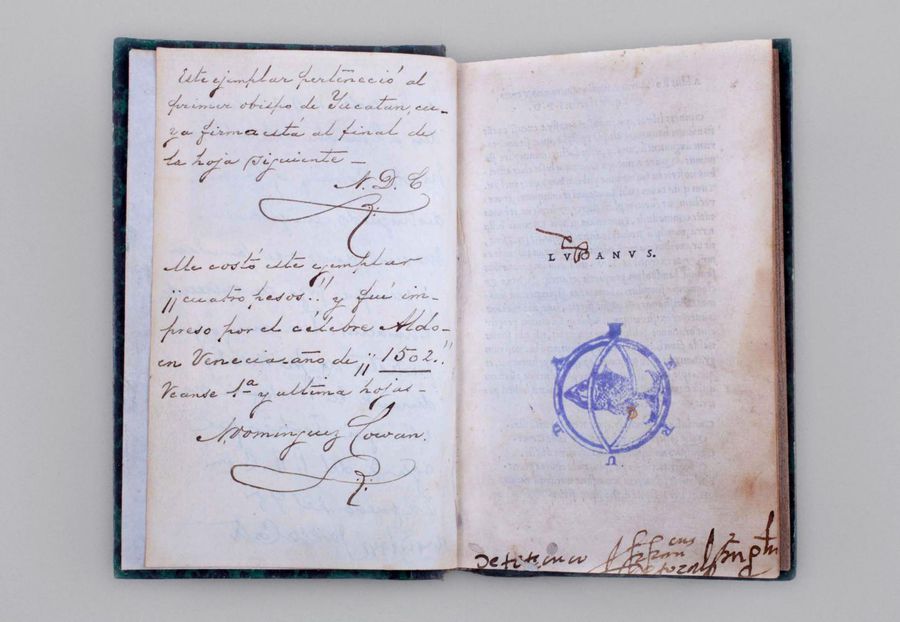

“Pharsalia (también conocida como Bellum civile), es un poema inacabado en diez cantos, el cual narra la guerra civil entre Julio César y Pompeyo, corresponde a un texto escrito en latín por el célebre poeta romano Marco Anneo Lucano (39- 65 d.c). Pertenece a la colección de 5.107 volúmenes donados por el poeta Pablo Neruda el año 1954 a la Universidad de Chile.

Se trata de una epopeya concebida en orden cronológico y considerada un clásico dentro del canon de la literatura antigua.

El libro fue compuesto en el siglo XVI por la imprenta del humanista e impresor italiano Aldus Manutius (1450-1515), quien fuera reconocido como el más grande tipógrafo de su tiempo, por haber dado forma a criterios importantes de edición, tales como la puntuación, la invención del punto y coma, de los caracteres cursivos, la numeración de las páginas y el formato en octavo.”

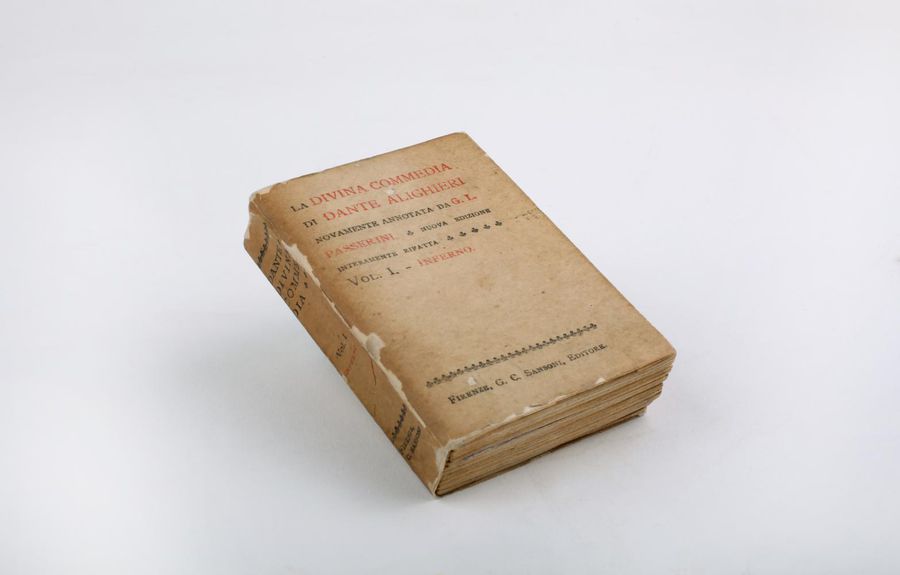

“Edición en pequeño formato de la obra del poeta Dante Alighieri (c. 1265-1321), publicada en italiano, en la ciudad de Florencia el año 1915. Fue compuesta por G. C Sansoni Editore. Incluye antecedentes biográficos del autor y anotaciones página a página. Pertenece a la Colección donada en 1954 por Pablo Neruda a la Universidad de Chile, conjunto que fue declarado Monumento Histórico Nacional en 2009.”

![Víctor Hugo, Les travailleurs de la mer [maquette], Librairie Internationale A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et C. Editeurs, Paris, 1866, 2 vólumenes.](https://pabloneruda.bibliofilos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/thumb-3.jpg)

“Pruebas de imprenta de la primera edición del libro Les travailleurs de la mer, texto escrito por Víctor Hugo (1802- 1885), poeta, novelista y dramaturgo francés considerado como uno de los mayores exponentes literarios del siglo XIX. “

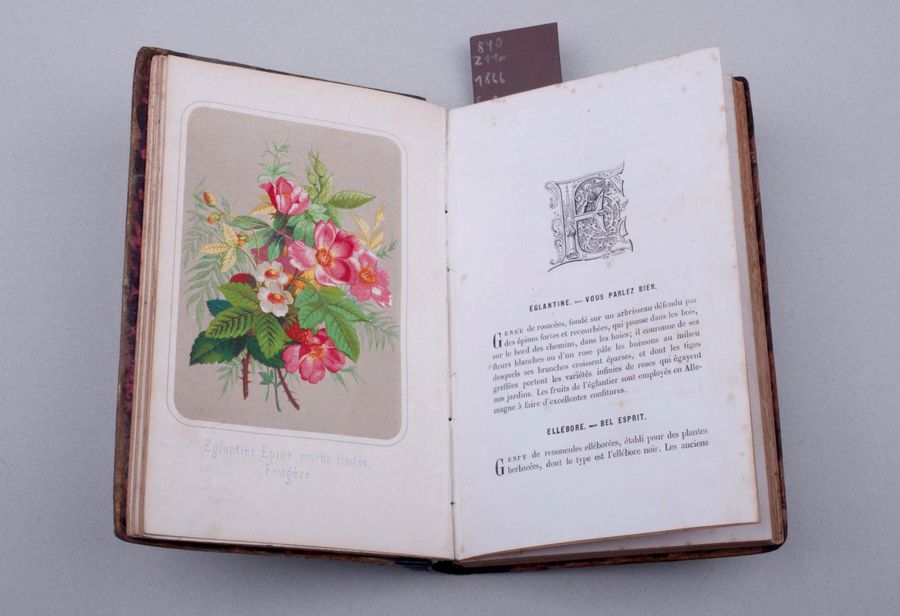

Nouveau langage des fleurs es un libro único en Chile. “El texto, sin autor preciso, tiene tres objetivos: identificar conceptualmente el lenguaje existente de manera implícita en cada una de las flores ordenadas por tipos y nomenclaturas precisas; interpretar el valor simbólico de las mismas; y ejemplificar el uso literario, novelesco y poético que las flores han tenido, considerando el trabajo de múltiples escritores europeos, entre los que se encuentra el eminente Honoré de Balzac. Al final del libro encontramos poesías y narraciones al respecto.”

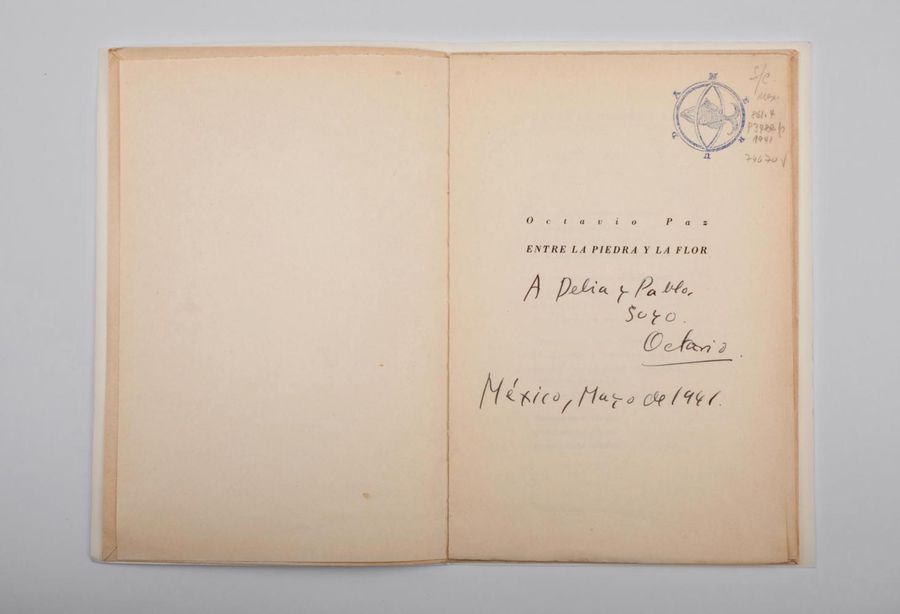

“Libro editado por el sello mexicano Nueva Voz en 1941, dedicado por su autor a Pablo Neruda y a su entonces esposa Delia del Carril el mismo año de la publicación. Octavio Paz (1914-1998), poeta, ensayista, traductor y destacado intelectual mexicano trabó amistad con Pablo Neruda en el contexto del II Congreso Internacional de Escritores en Defensa de la Cultura, España, 1937.” Más tarde, en 1990, Octavio Paz obtuvo el Premio Nobel de Literatura.

Lawyer. Partner of the Chilean Bibliophile Society.

My name is Franco Brzovic, a member of number of the Society of Chilean bibliophiles. I am pleased to tell you about an interesting book by Neruda titled “All the Love”, which is a personal anthology. It is a first edition that also has some special characteristics. In this document, you will be able to appreciate the letter by the author in which he entrusts Guiseppe Bellini to edit this book in 1968, in Spanish and Italian. The book, unlike some others, has retained the first page and the dedication page. The book was acquired in Catania, Sicily, some time ago after I toured numerous bookstores.

Degree in History and Master in History and Management of Cultural Heritage. Director of the Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile.

Interview

When was the Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs created and what are its objectives?

The Ministry of Foreign Relations was created in 1871 and the first record of the operation of its archive is a circular dated November 23, 1901, which aims to organise the internal system of archives.

Later provisions separated the Historic Archive from the Registry Office and designated it as the General Historical Archive, with the sole function of preserving and ordering all the documents of the Chancellery. At present, the archive is a Department that depends on the Undersecretariat of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, whose structure and objectives have become more complex.

Nowadays, its main functions are related to an integral archival management and its main objectives are focused on describing, preserving, and giving access, according to international and national standards, to the documentation originated and received by this Ministry. In addition, his function is to contribute to the transparency of information by attending to requests for transparency and inquiries from users, both in person and by email. This has become an important part of the work of our archive.

The main topics that can be investigated from our documents are diplomatic and consular management, bilateral relations with neighbouring countries, colonization and immigration, foreign trade, participation in international organizations and institutional history itself, among others.

What emblematic projects have you carried out in the Historical Archive?

Since 1994, the General Historical Archive has carried out important projects that have been financed with private or state funds, which have focused mainly on the organization, description and cataloguing of some of our documents collections, and on digitization and conservation of photographs belonging to our photographic archive.

• During 1994 and 1995, the Project for the Installation and Equipment of the Conservation Laboratory Restoration of the Paper Laboratory was carried out, with funds provided by Fundación Andes.

• Between 1998 and 2002, the Border Countries Archive Conservation and Cataloguing Project was carried out.

• In 2005 the Conservation and Cataloguing Project of the Photographic Collection of the Chancellery was carried out, with funds contributed by Harvard University.

• Between 2012 and 2013, 3,500 photographs were digitized for displaying the Photographic Archive in our catalogue on the website, which was financed by the Heritage Trust Project of the EMC Company.

• Between 2014 and 2016, the project “Enhancement of the Immigration Fund: Organization, Assessment and Description of Documentation” was carried out, stages 1 and 2, with funds from RADI.

• Between 2018 and 2020, the two phases of the project “Cataloguing the International Organizations Fund: First Stage (1983 – 1990) and Second Stage (1990 – 1992)” were carried out, also with funds contributed from RADI.

• Between 2019 and 2020, thanks to funds granted by RADI, the project “Conservation and Digitization of the Albums of the Chilean Chancellery Archive” was executed.

The photos of Neruda from the trip to the USSR, what year are they and for what reason?

The photographs of Pablo Neruda in the USSR correspond to a trip carried out in 1950 from Mexico, aboard the “steam Argentina”, which made a brief stop in Cuba.

In Moscow, he attended a meeting with communist representatives from around the world, in which was discussed the organization of a communist resistance army in each of the Latin American countries.

What were the diplomatic positions held by Pablo Neruda?

Starting his first diplomatic stage, Pablo Neruda was appointed in 1927 as Consul of Chile in Rangoon, Burma. In the period from that year to 1933, he also served as Consul in Colombo, Batavia and Buenos Aires.

In 1934 he assumed the position of Consul of Chile in Barcelona and the following year in Madrid. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 meant a hiatus in his diplomatic work, causing his return to Chile in 1937.

In 1939 he settled as Consul of Chile in Paris, from where he managed one of his greatest contributions as a representative of our country abroad. He organised the Winnipeg ship trip, which brought more than 2,000 Spaniards who chose Chile as the country of asylum.

Finally, in 1940 he was assigned as Consul to Mexico and between March 1971 and the end of 1972 he served as Ambassador in Paris.

1927: Consul of Rangoon, Burma.

1930: Consul in Batavia, Java.

1933: Consul in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

1934: Consul in Barcelona, Spain.

1935: Consul in Madrid, Spain.

1939: Consul in Paris, France, for Spanish immigration.

1940-1943: Consul in Mexico City.

1971-1972: Ambassador to Paris, France.

Doctor of Literature. Professor, University of Chile. Poet.

Reading of a fragment of “Heights of Machu Picchu”

Good afternoon, here I am with the first edition of Song of the Americas, edited by Edición América. It is not the first, but the first edition at least in Chile. And I want to read you a fragment of “Heights of Machu Picchu” written by our great Pablo Neruda and comment on, at least, some of the most important things that in my view are in the text.

The first thing I would like to say before reading it is about the position of the speaker. The speaker or the poet expresses himself in a way of saying things so that he resembles the voice of America. In some way, it is the wonder of being the prophet poet, the Promethean poet, that somehow it tells us that he foresees the future of our America.

Obviously, I am not going to read this text in full, but it links, let us put it this way, the concept of being, and as it says in a verse: the great poet or the great speaker or the great voice that comes to speak through your dead mouth.

Obviously, these verses that were musicalized by “Los Jaivas”, are verses that, in the tone of a song or Venezuelan rhythm, immediately come to our ears:

Arise with me, American love.

Arise to birth with me, my brother.

Give me your hand out of the depths

sown by your sorrows.

You will not return from these stone fastnesses.

You will not emerge from subterranean time.

But I would like to stop at another text that, perhaps, people do not remember as so crucial within this same poem. I am referring to part IX, the fragment IX of this wonderful text, which I insist, comes to take the entire American origin and link it with our own current destiny. I am referring to this text, which I want to highlight and underline, that uses the adjective and the noun in an extraordinary way.

Listen to a wonderful fragment of the “Heights of Machu Picchu”:

Sidereal eagle, vineyard of mist.

Bulwark lost, blind scimitar.

Starred belt, sacred bread.

Torrential ladder, giant eyelid.

Triangled tunic, pollen of stone.

Granite lamp, bread of stone,

Mineral serpent, rose of stone.

Buried ship, wellspring of stone.

Lunar horse, light of stone.

Equinox square, vapor of stone.

Final geometry, book of stone.

Iceberg carved by the squalls.

Coral of sunken time.

Rampart smoothed by fingers.

Rood struck by feathers.

Branching of mirrors, ground of tempests.

Thrones overturned by twining weeds.

Rule of ravenous claw.

Gale sustained on the slope.

Immobile turquoise cataract.

Sleepers’ patriarchal bell.

Collar of subjected snows,

Iron lying on its statues.

Inaccessible storm sealed off.

Puma hands, bloodthirsty rock.

Shading tower, dispute of snow.

Night raised in fingers and roots.

Window in the mist, hardened dove.

Nocturnal plant, statue of thunder.

Root of the cordillera, roof of the sea.

Architecture of lost eagles.

Cord of the sky, bee of the heights.

Bloodstained level, constructed star.

Mineral bubble, moon of quartz.

Andean serpent, brow of amaranth.

Dome of silence, purebred homeland.

Bride of the sea, cathedral tree.

Salt branch, blackwinged cherry tree.

Snowswept teeth, cold thunder.

Scraped moon, menacing stone.

Crest of the cold, pull of the air.

Volcano of hands, dark cataract.

Silver wave, direction of time.

(This poem was translated by John Felstiner in Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu, John Felstiner, Stanford University Press, 1980).

I believe that this small fragment, fragment IX of the Canto General is, without a doubt, one of the finest proofs that a poet can provide of greatness.

I believe, as Pablo Neruda – who was “the enemy” of Vicente Huidobro – said the adjective kills when it does not give life. And here, precisely, is where the adjective gives the greatest life and builds, through the word, a universe that may be lost, but that returns to us in one way or another.

Third Residence Reading (1947)

How are you? Perhaps this is one of Pablo Neruda’s texts that most stirs the conscience of all of us, as it is a text that implies the change from the surrealist writing to the socialist realism writing style. It happens without falling excessively to the communist or the partisan side.

In this book, Neruda draws our attention to the tragedy of a war, the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War. A war that, without a doubt, has a profound significance for me, given that I am the son of one of the exiles who arrived on the ship Winnipeg. This was possible thanks to Pablo Neruda, the Government of Pedro Aguirre Cerda and the government of the Spanish Republic in exile.

And this poem, which many of you probably know, shows why his poetry changes, why he no longer writes in surrealist or in the avant-garde style. He moves forward, explores the condition of the people, the condition of suffering the wounds of the pain of others. The poem is part of “Third Residence”. Here I have the first edition “Editorial Losada” from 1947 and the fragment that I am going to read from this book, which is Spain in the Heart, the great poem that he writes about the Civil War, is the fragment “I explain some things”.

You are going to ask: and where are the lilacs?

and the poppy-petalled metaphysics?

and the rain repeatedly spattering

its words and drilling them full

of apertures and birds?’

I’ll tell you all the news.

I lived in a suburb,

a suburb of Madrid, with bells,

and clocks and trees.

From there you could look out

Over Castille’s dry face:

a leather ocean.

My house was called

the house of flowers, because in every cranny

geraniums burst: it was

a good-looking house

with its dogs and children.

Remember, Raúl?

Eh, Rafael?

Federico, do you remember

from under the ground

where the light of June drowned flowers in your mouth?

Brother, my brother!

Everything

loud with big voices, the salt of merchandises,

pile-ups of palpitating bread,

the stalls of my suburb of Argüelles with its statue

Like a drained inkwell in a swirl of hake:

oil flowed into spoons,

a deep baying

of feet and hands swelled in the streets,

metres, litres, the sharp

measure of life,

stacked-up fish,

the texture of roofs with a cold sun in which

the weather vane falters,

the fine, frenzied ivory of potatoes,

wave on wave of tomatoes rolling down to the sea.

And one morning all that was burning,

one morning the bonfires

leapt out of the earth

devouring human beings –

and from then on fire,

gunpowder from then on,

and from then on blood.

Bandits with planes and Moors,

Bandits with finger-rings and duchesses,

Bandits with black friars spattering blessings

came through the sky to kill children

and the blood of children ran through the streets

without fuss, like children’s blood.

Jackals that the jackals would despise,

stones that the dry thistle would bite on and spit out,

vipers that the vipers would abominate!

Face to face with you I have seen the blood

of Spain tower like a tide

to drown you in one wave

of pride and knives!

Treacherous

generals:

see my dead house,

look at broken Spain:

from every house burning metal flows

instead of flowers,

from every socket of Spain

Spain emerges

and from every dead child a rifle with eyes,

and from every crime bullets are born

which will one day find

the bull’s eye of your hearts.

And you will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

(This poem was translated by Nathaniel Tarn. From: Pablo Neruda Selected Poems: A Bilingual Edition, Houghton Mifflin / Seymour Lawrence, Boston, 1970)

This extraordinary poem by Neruda evokes the terrible tragedy that can touch us at any moment: Syria, Lebanon, Libya. Any place in the world can be the terrible place where we lose our children, where we lose the blood of our fellow men, where our home is destroyed. That is why the poet changes his style, changes his form, changes his saying to also enter once more into the absolute convulsion of deepest humanity. The terrible tragedy and the wonderful joy of being human.

Economist, academic, writer and member of the Chilean Bibliophile Society.

Obras Completas

Colección de las Obras Completas, publicadas por la Editorial Cruz del Sur, en 10 volúmenes muy pequeños en 1947. Se distribuyó por suscripción a un número limitado de personas (casi todos norteamericanos y europeos, muy pocos chilenos) y nunca salió a la venta en librerías.

Arriba, a la izquierda: primera edición de Canto General, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, Ciudad de México, 1950.

Arriba, a la derecha: primera edición de Las Uvas y el Viento. Editorial Nascimento, Santiago de Chile, 1954.

Abajo, se puede apreciar el pequeño tamaño de las Obras Completas

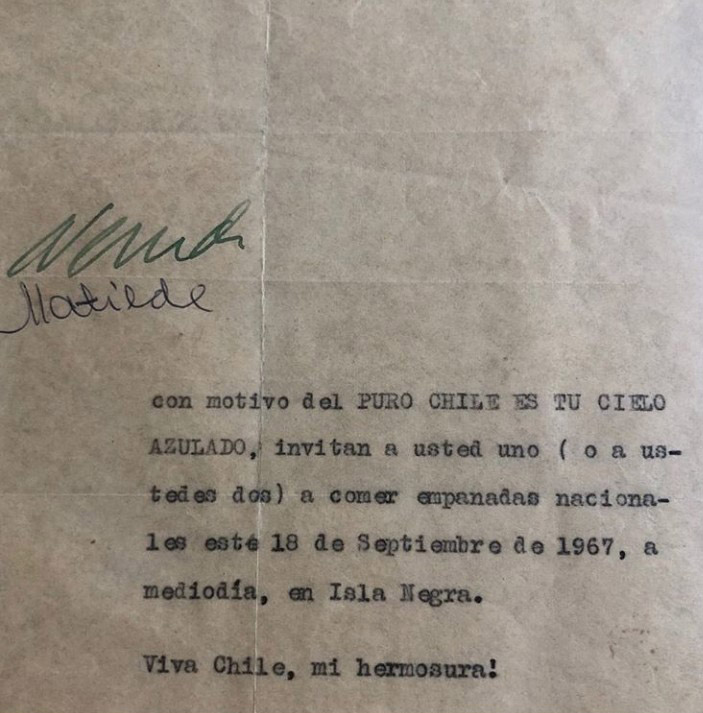

Cada ejemplar de esta colección fue autografiado por Pablo Neruda, con su característica tinta verde.

Norma Alcamán Riffo, Bachelor in Literature and Master in Literature. Diploma in Cultural Administration. Writer.

Director of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and Member of the Società Bibliografica Toscana, in Italy. Director of this virtual exhibition.

Splendor and death of Joaquín Murieta (1967): Neruda’s only dramatic work.

When a prominent person is commemorated, especially if he is a great writer, painter or musician, various activities are usually carried out and his work is reconsidered from new perspectives, which shed new light on his understanding and update his contribution to a discipline. Accordingly, the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Nobel Prize for Literature conferred to Pablo Neruda in 1971 is an invitation to reread, study and analyse his work, and to value those parts that merit it.

In the context of the extensive creation of Neruda’s, The Splendour and Death of Joaquin Murieta is particularly interesting: it is a dramatic work which has versions in theatre and opera. Pablo Neruda defined it as follows: “This is a tragic work, but also, in part, it is written as a joke. It would like to be a melodrama, an opera and a pantomime”. Although it is understandable that the study of his extensive and profound poetic work occupies almost all the academic articles and books dedicated to his literary creation, it is also fair to take this particular work into consideration as well.

In 1966, Pablo Neruda published this only dramatic work with Editorial Zig-Zag, which launched its first edition with 10,000 copies, of which my parents – great readers – acquired number 7,076, which they kept in their library. In 1967, it was presented as a theatrical work for the first time at the Antonio Varas Theatre. Then, Neruda commissioned the music by the composer Sergio Ortega, who worked developing the aesthetic ideas of the text. As an opera, it was premiered at the Municipal Theatre of Santiago in 1998.

The play, set in 1850 during the gold rush, begins in Valparaíso when Joaquín Murieta embarks for California, seeking a better future. On the way, he marries Teresa, a Chilean from the countryside. It is a love match, so the couple legitimately wants to start a family. However, upon reaching California, the “greyhounds” (North Americans) rape and kill Teresa. This experience causes unfathomable pain in Joaquín Murieta, who responds with fury, transforming himself into a famous bandit motivated by revenge, until he is killed.

From a dramatic perspective, first, we note that it is a work that responds to the traditional structure proposed by Aristotle in Poetics, so that its aesthetic codes (unity of action, presence of incidents, anagnorisis, etc.), are readable by an international educated public.

When studying the work with the method of analysis of dramatic situations, established by Etienne Souriau in Le 200.000 situations dramatiques, it fully responds with the oriented force, the object desired, desired subject, opponent, assistant, and referee, that is, the six abstract forces that participate in the dramatic tension which is resolved at the end, immediately after the climax.

Second, we address the level of symbols and motifs. As for the symbols, the sea is the main one, which is complemented by the ship. In this journey, which is a symbol of life, we find a gallery of diverse characters.

Regarding the literary motifs, as we know, they have two meanings: as elements that move the dramatic action (since the motive comes from the Latin muovere) and also as recurring elements of the play. Now, in this particular case, in its first sense, we find love, greed, destiny and, in its second sense, we find travel, friendship, and revenge. These and other elements are intertwined in such a way around a central axis, which ultimately determines the theme: the eternal struggle of good and evil, which are present throughout the whole story.

Third, the litmus test of any literary work is time. In this case, it is still valid in the tradition -innovation duality. Indeed, our poet and his playwright bring together elements of Greek theatre, such as the presence and role of the choir within the dramatic structure, as well as the tragic destiny of the protagonist and qualifies it with elements of the Noh theatre that he saw in Yokohama; all of this, set on the ship and later in the city of San Francisco, California in 1850. Certainly, the result is original and well achieved. More than 50 years have passed; however, this piece is still full of meaning, maintains its liveliness and carries an ever-living message.

Based on the foregoing, we can assert that Neruda’s only dramatic work, has several levels of meaning: literal, symbolic and mythical, because by turning Joaquín Murieta into a tragic hero and elevating him to the category of Chilean myth, placed it in an abstract and perennial setting.

This play is key to establishing that Neruda was a complete writer, as he cultivated the lyrical, narrative and dramatic genres, always with different nuances, talent and great sensitivity. He also possessed knowledge of the literary tradition and knew how to update it with his vision, which allowed him to be part of the pantheon of world literature.

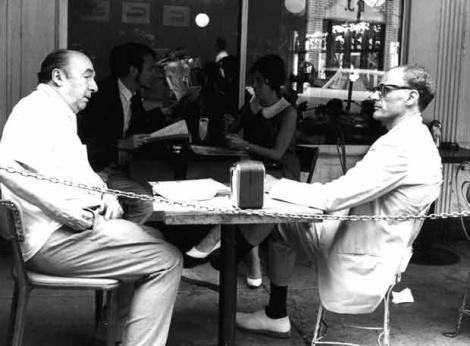

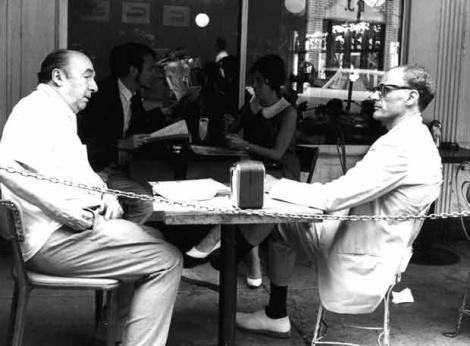

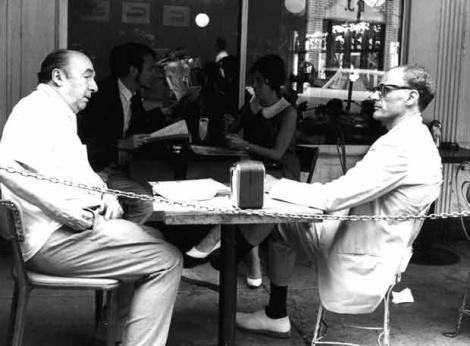

Pablo Neruda con el dramaturgo norteamericano Arthur Miller (New York, 1966).

Pablo Neruda with the playwright Arthur Miller (New York, 1966).

Gynecologist-obstetrician. Partner of the Chilean Bibliophile Society.

Edgardo Corral was born in 1954 in Rancagua, 10 kilometres south of Santiago. He is a gynaecological obstetrician, a specialist in foetal medicine. Currently, he is the Head of the GO Service and has been directing an intrauterine surgery program since 2012 at the Rancagua Hospital. He has published several articles in different international magazines, and he is the author of a couple of chapters in books on the area. He is also an academic at the Diego Portales University School of Medicine.

Edgardo grew up in the province and when he was a teenage student, he had the privilege of meeting Neruda personally, when Neruda visited his Lyceum around 1970. On that memorable day, his interest in Neruda’s universe was born, which he approached through an avid reading of his best known poetry. Later, he studied both the biography and the complete work of the poet, becoming a true cultist of Neruda.

Later, with time and travel, he realized that Neruda is the most universal character that Chile has. This was another motivation to passionately search for any document or memory that is related to his life and work. This is how, to this day, he is a recognized collector of first editions, letters, and some handwritten pieces by Neruda. In addition, he has dedicated himself to research and writing articles on unknown, but important, topics that belong to Neruda’s life. Among others, he published in the magazine of the Neruda Foundation a scientific analysis on the birth in Madrid of Neruda’s only daughter, Malva Marina. He also participated together with the Mayor, in the inauguration of Pablo Neruda Street in Saint-Avertin near Paris and he is working on a draft describing the friendly relationship between Neruda and Baltazar Castro, a politician and writer from Rancagua, his hometown.

Volodia Teiltelboim: friend, comrade and fellow poet

Volodia Teitelboim was a lawyer and an important Chilean politician during the 20th century. In addition, he stood out as a writer. He was part of the group known as The Literary Generation of 1938, and he received the National Prize for Literature in 2002. In this context, he was one of Pablo Neruda’s greatest friends, from 1937 until the poet’s death in 1973, and they were partners in political struggles and colleagues in the field of letters.

Volodia Teitelboim was born in Chillan in Chile in 1916, the same year that Rubén Darío died. During the 1930s, he participated as part of the revolutionary movement in art and socialism. He entered the Communist Youth Party and studied law at the University of Chile without losing his passion for poetry. In 1935, with Eduardo Anguita, he published the Anthology of New Chilean Poetry, a book that caused a long controversy, because it did not include Gabriela Mistral or other important writers.

In 1952, Teitelboim published Sons of Nitrate with a foreword by Neruda in the second edition, after which came difficult days including an exile to Pisagua in the north of Chile in 1956. In the 1960s, he was a member of parliament in the low chamber and later Senator for Valparaíso. In the political world, he was recognized for his eloquence and oratory. At the beginning of the ’70s, the Nascimento Press published a little-known book, The Trade of a Citizen, where Neruda once again wrote a foreword for him with true devotion to his qualities as a committed intellectual, and generating, according to Neruda, “a new dimension of politics”. Then came self-imposed exile in Moscow. Upon his return to the country after 15 years, he published during the ’80s and’ 90s biographies of Neruda, Mistral, Borges and Huidobro, written with great literary rigour.

His biography about Pablo Neruda is one of the most complete and unique, since in it he manages to reveal the poet in his human aspect. This book brings the virtues of a chronological essay, although it indicates that the true biography of Neruda is in his poetry, where he captured all the calls of life.

SIEMPRE

Antes de mí

no tengo celos.

Ven con un hombre

a la espalda,

ven con cien hombres en tu cabellera,

ven con mil hombres entre tu pecho y tus pies,

ven como un río

lleno de ahogados

que encuentra el mar furioso,

la espuma eterna, el tiempo!

Tráelos todos

adonde yo te espero:

siempre estaremos solos,

siempre estaremos tú y yo

solos sobre la tierra

para comenzar la vida!

Pablo Neruda

Poet. Partner of the Chilean Bibliophile Society.

Part of his Nerudian collection is contained in this book:

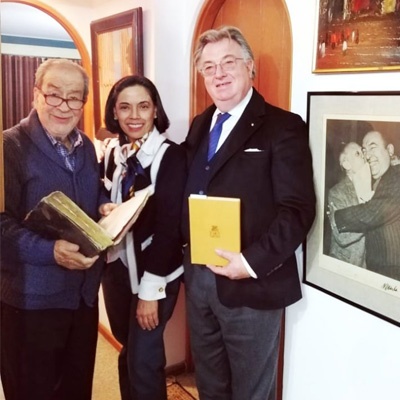

The lawyer Nurieldín Hermosilla, a member of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles, receives at his home a visit from Norma Alcamán Riffo and Paolo Tiezzi Mazzoni della Stella Maestri, President of the Società Bibliografica Toscana. Next to them, the photo of Picasso and Neruda in a friendly

The Book of Leaves, a unique hand-made copy.

“The Book of Leaves

by Pablo Neruda

Paris

November 1971

Unique specimen made for Ugne Karvelis.”

“The leaves are falling

from a

forgotten autumn.

Falling towards the

abyss of the

light.”

Ignacio Swett is a Civil Engineer and is currently a member of the Board of Directors of a steel company and of the Puente Foundation, which aims to help vulnerable young people. As a bibliophile, he is a recognized collector of first editions of Chilean history, of Gabriela Mistral (Nobel Prize in Literature 1945) and Pablo Neruda.

Video subtitled in Spanish and Italian

Vídeo subtitulado en español e italiano

In 1998, I received a telephone call from a person who knew about my bibliographic hobbies and about my interest for first editions of Pablo Neruda’s work. He told me he had a book that he thought might interest me because it was signed by Neruda and because in the colophon, it was established that the edition consisted of only 10 copies.

This person took it to my office and as soon as I saw it, I knew I would buy that copy. It was a book entitled Two Poems, of which I had no reference whatsoever.

I acquired the aforementioned book and, as soon as I could, I went to the Neruda Foundation to request information on those “Two Poems”. Talking to Tamara Waldspurger I learned the story that I comment on below.

The penultimate work of Pablo Neruda, published during the poet’s lifetime, was “Four Poems Written in France”. This work, as its name implies, consists of four poems, namely: The Ocean is Calling; Homer Arrived; The Bell Tower of Authenay and The Skin of the Birch.

As Neruda himself says in a “declaratory note” at the end of the book, these and other poems were written in 1972, during his car trips between the Chilean Embassy building and his house in Condé-Sur-Iton, in French Normandy.

The colophon of this work says verbatim:

“This work consists of 300 numbered copies, the first 100 from I to C, printed on special feather paper with a fantasy paper cover, plus 200 copies numbered from 101 to 300 on special feather paper with a printed cardboard cover. All copies bear the signature of the author. The printing was made in the workshops of Editorial Nascimento and finished on December 31, 1972 “

When this book was published, one of the printing workers took the first and the fourth of the aforementioned poems and, without the authorization or knowledge of the author, proceeded to print a book that he called “Two Poems.” This book consists of twenty-four unnumbered pages, where only the odd or right-hand pages are used, and has the same typeface and layout and the same printing date as the book “Four Poems Written in France”.

“This work consists of 300 numbered copies, the first 100 from I to C, printed on special feather paper with a fantasy paper cover, plus 200 copies numbered from 101 to 300 on special feather paper with a printed cardboard cover. All copies bear the signature of the author. The printing was made in the workshops of Editorial Nascimento and finished on December 31, 1972 “

When this book was published, one of the printing workers took the first and the fourth of the aforementioned poems and, without the authorization or knowledge of the author, proceeded to print a book that he called “Two Poems.” This book consists of twenty-four unnumbered pages, where only the odd or right-hand pages are used, and has the same typeface and layout and the same printing date as the book “Four Poems Written in France”.

“Esta edición consta de 10 ejemplares, impresos en cartón prensado, numerados de la letra A a la J y firmados por el autor. La impresión fue hecha en los talleres de la Editorial Nascimento y terminada el 31 de diciembre de 1972”

El operario que hizo estos 10 ejemplares fue un día a Isla Negra y le presentó a Pablo Neruda el resultado de “su atrevimiento”. Dicen que al poeta no le pareció bien el proceder de este operario pero que, finalmente, se rindió ante esta osadía y firmó los diez ejemplares que le presentó el personaje en cuestión.

No se sabe si Neruda se quedó con algún o algunos de estos ejemplares, aunque lo más probable es que así fuera, ni quienes puedan ser – actualmente – los poseedores o dueños de los restantes. El ejemplar de “Dos poemas” que cayó en mis manos es el Ejemplar letra J de esta particular y poco conocida edición.

Cabe hacer mención que “Dos poemas” no aparece mencionado en la bibliografía de Neruda hecha por Horacio J. Becco, la que incluyó “Cuatro poemas escritos en Francia”. En las Obras Completas editadas por Hernán Loyola no se menciona la obra “Cuatro poemas escritos en Francia” y, por lo tanto, tampoco se hace mención a “Dos poemas”.

It is also worth mentioning that of the poems in the book “Four Poems Written in France”, only the one entitled “The Bell Tower of Authenay” was published before the aforementioned book. Indeed, it appears in “Unfruitful Geography”, a book published in Buenos Aires by Editorial Losada, printed in May 1972.

The poems “The Skin of the Birch” and “Flame the Ocean” were included in the work “Winter Garden”, published in Buenos Aires by Editorial Losada, printed on January 8, 1974.

Finally, the poem “Homer Arrived” was included in the book “Chosen Defects”, also published in Buenos Aires by Editorial Losada and was printed on July 28, 1974.

Enrique is an architect and a writer. He is currently the Director of the Society of Chilean Bibliophiles and is also a music producer. In Chile, he has produced “My Fair Lady”, “Cabaret”, “The Sound of Music”, “Chicago”, “Cats” and “A Chorus Line”. In 2008, thanks to his management, Ennio Morricone performed for the first time in Chile with huge success, accompanied by the Symphony Orchestra of Rome and he also performed with the Choir of the University of Chile. Enrique is the First Vice President of the Pablo Neruda Foundation and a collector of his work, and during his youth he met the poet.

Vídeo subtitulado en español e italiano

Italian singer-songwriter, very loved by the Chilean public. He won the popular music competition at the LVI Viña del Mar International Song Festival in 2015.

Poem 20

Hello friends, I am Franco Simone and I am a singer-songwriter, but I am also a huge admirer of Pablo Neruda’s poetry. In addition, I would add that Pablo Neruda is, absolutely, my favourite poet.

Exactly 50 years have passed since the Nobel Prize was awarded to this great poet. I invite you all to visit the Italo-Chilean virtual exhibition “Pablo Neruda: 50 Years of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1971-2021)”.

What would you say about this poet? I have always admired his originality, his great spirituality, which became something carnal. He always knew how to unite spirit with eroticism. At times, he seemed not very modest, but without ever being indecent or transgressive. There is always something to learn when reading Neruda. Today I wanted to read some verses from his beautiful Poem 20:

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

Write, for example,’ The night is shattered

and the blue stars shiver in the distance.’

The night wind revolves in the sky and sings.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.

Through nights like this one I held her in my arms

I kissed her again and again under the endless sky.

She loved me sometimes, and I loved her too.

How could one not have loved her great still eyes.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines.

To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the immense night, still more immense without her.

And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture.

What does it matter that my love could not keep her.

The night is shattered and she is not with me.

This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance.

My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

My sight searches for her as though to go to her.

My heart looks for her, and she is not with me.

The same night whitening the same trees.

We, of that time, are no longer the same.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her.

My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing.

Another’s. She will be another’s. Like my kisses before.

This is Pablo Neruda

Poet from Capri, Italy.

Annalena is a poet who was born in and lives in Capri. She has always been passionate about art and literature. In 2012, she began her poetic and literary career. She has participated in numerous national and international poetry and literature competitions, receiving prestigious awards. One such award was presented in 2017, when she won the Prize for Culture in the “Luca Romano International Literature Prize” (Chieti). Annalena has participated in and organized art exhibitions and poetry events and also, she has authored prologues and reviews and been on the jury for literary competitions. In addition, she has published four books of poetry and her works are in numerous anthologies.

Libri pubblicati dalla poetessa caprese Annalena Cimino: L’amante della luna. Poesie e aforismi (2015), Fragile come un fiore di cristallo. Poesie e aforismi (2016), Rapsodie d’autunno. Poesie (2017) e Ali di un sogno. Poesie (2020). Tutti i libri, pubblicati da Intermedia Edizioni, Orvieto (Terni, Umbria).

Presencia de Neruda en Capri

Since 1990, she has been a librarian at the Ignazio Cerio Capri Centre. Carmelina graduated in Modern Foreign Languages and Literature from the Oriental University Institute of Naples. She has researched the subject of English writers and travellers on Capri, also publishing numerous articles on the subject. For the Capri Centre she has been the Curator of the exhibitions “History of an Island and a Library”, “The Pagano Hostel: a family, their house, their guests”, “Three Centuries of Travellers in Capri”, and “Capri and the World in Drawings by Laetitia Cerio “.

Capri, reina de roca

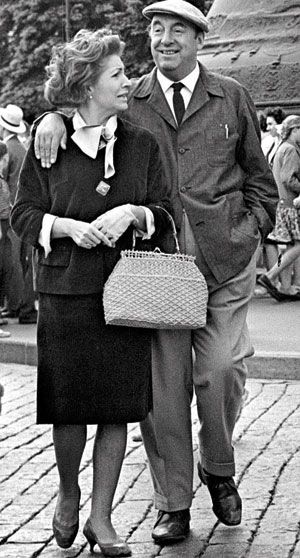

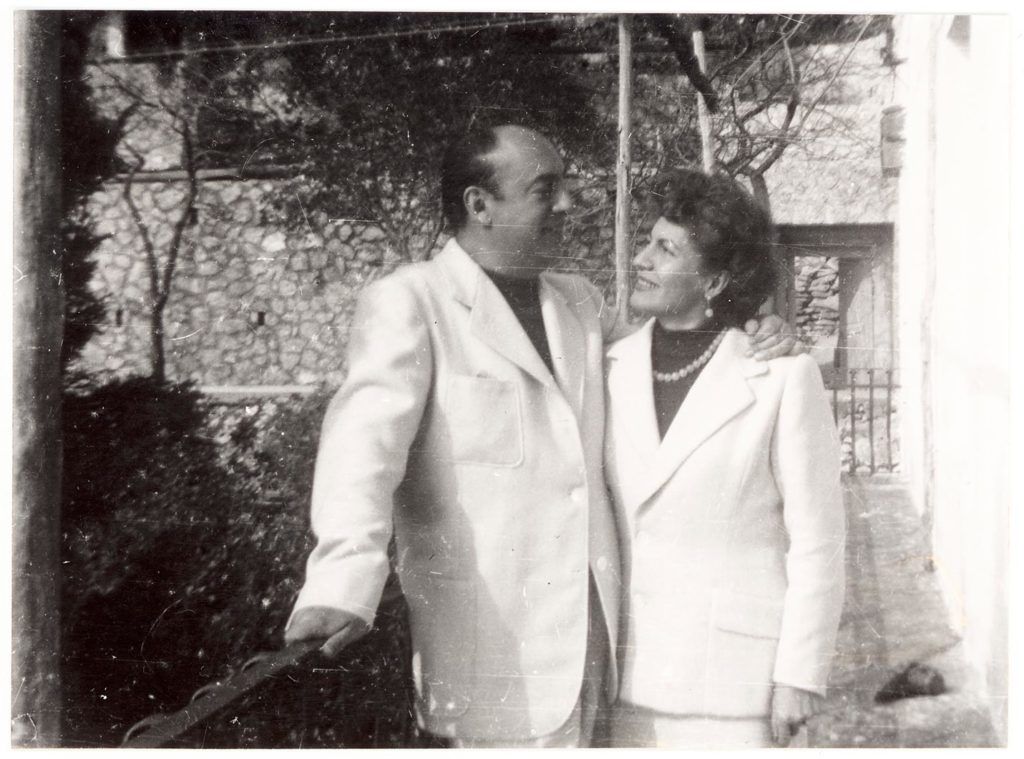

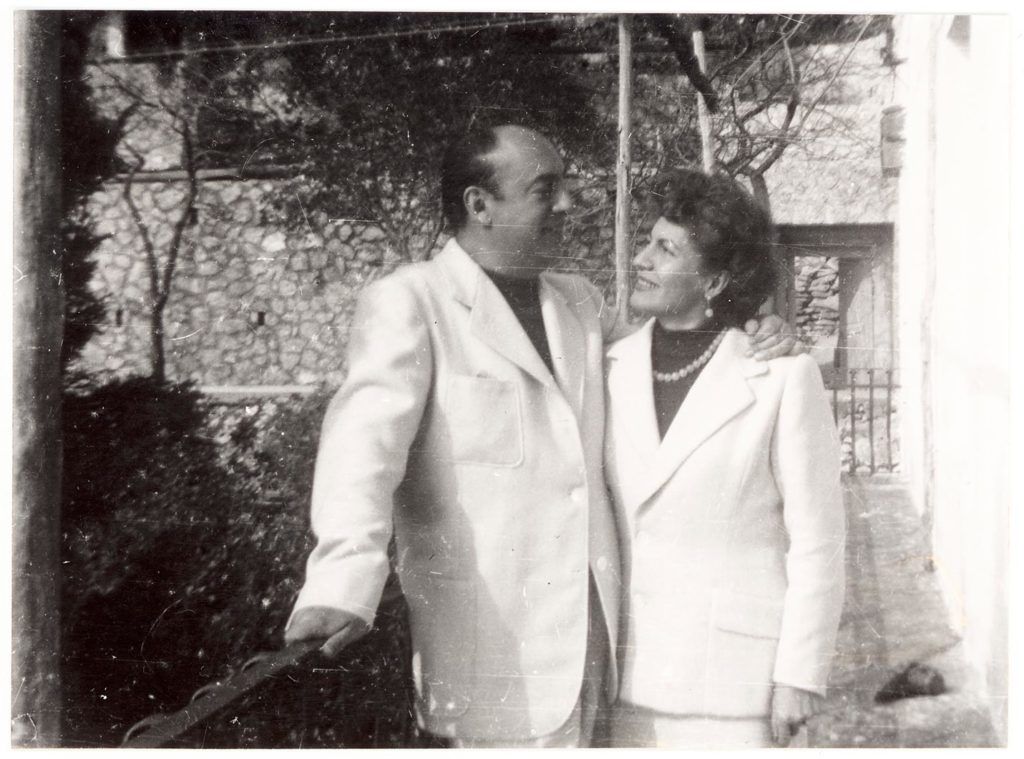

It was a dark winter evening when Pablo Neruda and Matilde Urrutia arrived at “Arturo’s Casetta” in Capri. Edwin Cerio, who had made the house available for them, welcomed them at the light of the fireplace. A few days before, on 8 January 1952, the member of the Italian parliament Mario Alicata had written a heartfelt letter to Cerio, asking him to host the poet: “The great poet Pablo Neruda is in Naples and wishes to spend three months in Capri in order to finish his book on Italy (…) He would prefer living in a house, even a very tiny one, and not in a hotel or guesthouse (…) Perhaps I hope not to dare too much, could you see if you have one or two rooms available, somewhere?”

Edwin replied directly to Neruda, with a simple invitation telegram: “Come, I’m waiting for you in Capri. There is a villa, “Arturo’s Casetta”, ready to host you. There you will be undisturbed and you will have the possibility to finish your book and to rest”.

The six months they spent in La isla clandestina, as Neruda calls Capri, are documented by the epistolary between Edwin and Pablo, now preserved in Capri at the library of the “Ignazio Cerio” Centre. Such correspondence consists of 14 documentary units, mainly letters from Neruda, but also letters from Mario Alicata, as well as the minutes of some letters from Edwin, and an article celebrating the poet’s arrival on the island: “looking forward to your landing in a place where no curtain- of whatever metal- could be seen, and that has its borders only in the horizons of poetry and beauty” . Also there was an extraordinary invitation card “a beber una copa …” in tissue paper with Edwin’s face stylized on it, that was delivered on 25 March1952 to the owners of “Arturo’s Casetta”, invitation card that they luckily preserved. Most of the letters are written on rice paper bought in China and adorned with elegant designs of dragonflies, flowers and an ideogram: “it is my signature, in Chinese it means ‘three ears'”.

Edwin and Claretta Cerio were living across the road from Pablo and Matilde; the former lived in Villa Lo Studio, located right in front of “Arturo’s Casetta”, both were on via Tragara. They wrote to each other and the maid of both, Amelia, acted as “post woman”. They continued to write to each other also when Neruda and Urrutia moved to Via Li Campi, in a small house closer to the historic centre but certainly without the breathtaking view they had enjoyed in Marina Piccola. Apart from dealing with day to day issues and sometimes requesting advice, those letters clearly show the sense of hospitality, the commonality of interests, the curiosity for Edwin’s shell collections, the serenity that pervaded the couple and the inspiration that Neruda finds in the island’s natural beauties.

The letters between the two also reveal an incident that risked to undermine the relationship of esteem established between the guest and his landlord. Cerio, in making his home available, had established the condition that the poet – during his island stay – left apart his role as a communist militant. However, when he received a phone call from a Chilean who, arriving in Naples, asked him to speak with Neruda, he became worried and wrote to the poet: “I was very happy to make “Arturo’s Casetta”, available for you… it is in the tradition of Capri, of my family and of my small cultural centre to honour people of genius and intellectuals without asking them for any passports other than their work (…) as far as I am concerned, I have the shortcoming of disliking all sorts of politics (…) therefore, as I do not wish to sail under a false flag, I do beg you and your friends not to ascribe any political intention or manifestation to the hospitality I offered you”. The poet apologized for the inconvenience and assured that no political activity had taken place “as for your flag, I already knew it, a flag that rises with the colours and scents of your island” and promised him that there would be no more problems. And so it was.

On the island there was no reason for secret encounters with Matilda, as Delia del Carril was on the other side of the planet: they felt finally free to love each other, to do long walks to Anacapri climbing up the Phoenician Scale and to organize parties with their friends from of Rome and Naples. Pablo also devised a peculiar ceremony so that the love that bound them would be blessed by Capri’s moonlight.

Cerio – among other things – was fond of the island’s nature and Neruda was for him an interested interlocutor. For this he wanted to present the poet with a booklet of his, dealing with the blue lizard from Faraglioni, that had been printed on “Amalfi paper” and was at the time out of print. The present was extremely welcomed by Neruda..

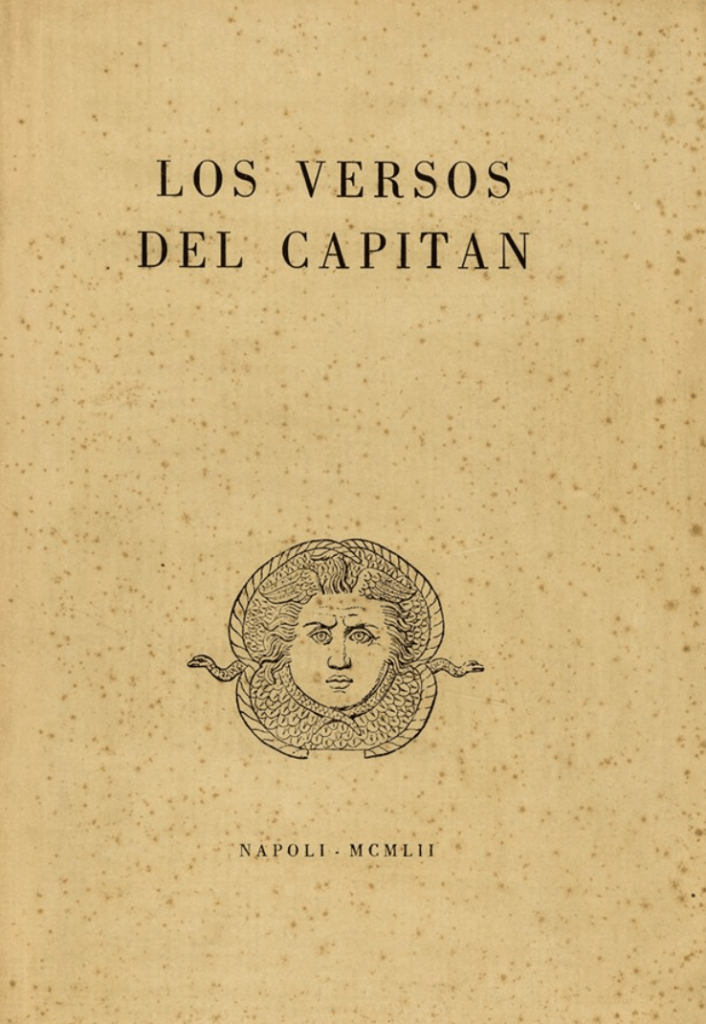

When thanking his friend, Neruda made him apart of a project he has in mind: the publication of a book of poems dedicated to Matilda, Los Versos del Capitan. Quiet and peace on the island were ideal in order to allow him to finish his work. This collection will be published anonymously later on, by Paolo Ricci in July 52, when the poet had already left for Chile. It was published only in 44 copies out of commerce, each with the name of a subscriber. Apart from Cerio, there were Quasimodo, Guttuso, Giorgio Napolitano, Vasco Pratolini Palmiro Togliatti, Luchino Visconti, Giulio Einaudi, Renato Caccioppoli. To go today through that list (included before colophon at the end of the volume), it is like to reading a chapter of the history of this country.

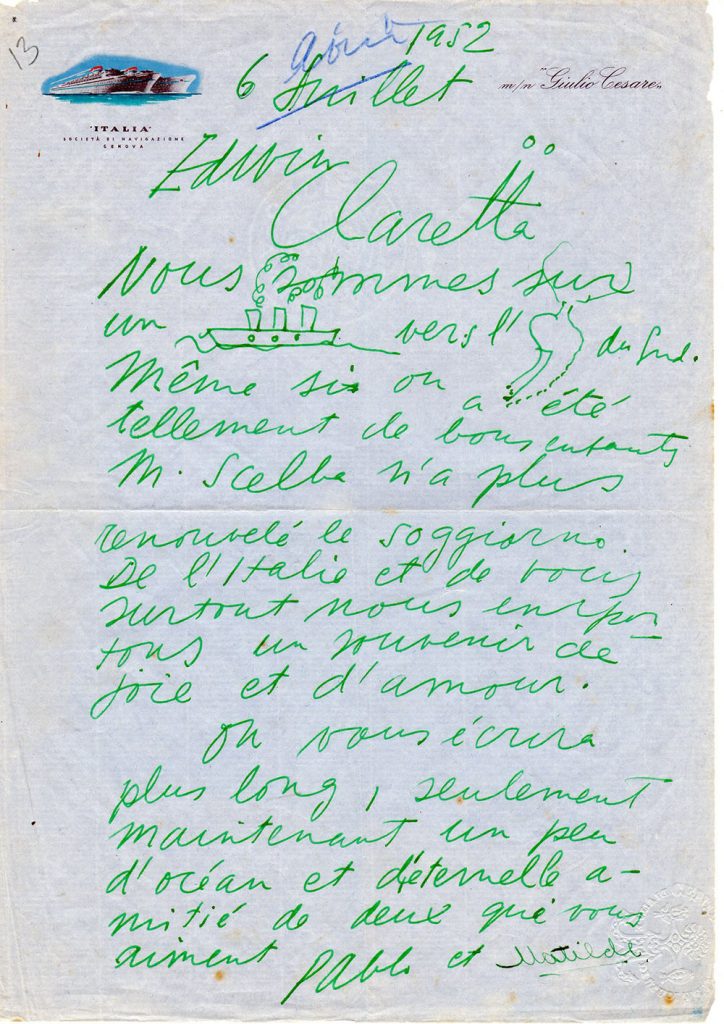

The last letter to Edwin and Claretta, the one written when the poet was already sailing back to Chile on the motor ship Giulio Cesare, after Scelba had not renewed his residence permit, expresses the gratitude of Pablo and Matilde and their affectionate greetings to their friends in Capri. Friends that were not going to be forgotten after the return in Chile and were going to be the recipients of kind presents even thereafter.

Bibliography:

[Pablo Neruda], Los Versos del Capitan, Napoli, Arte Tipografica, 1952

Pablo Neruda, Confesso che ho vissuto, Milano, SugarCo, 1974

Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Neruda a Capri, sogno di un’isola, Capri, Edizioni La Conchiglia, 2001

Teresa Cirillo Sirri (a cura di), Matilde Urrutia: La mia vita con Pablo Neruda, Firenze, Passigli, 2002

Pablo Neruda, L’uva e il vento: poesie italiane, a cura di Teresa Cirillo Sirri, Bagno a Ripoli, Passigli, 2004.

Bibliografía:

Cover of Los Versos del Capitán, Napoli, 1952.

| 1 | Matilde Urrutia | 23 | Paolo Ricci |

| 2 | Neruda Urrutia | 24 | Antonello Trombadori |

| 3 | Pablo Neruda | 25 | Giuseppe De Santis |

| 4 | Biblioteca Caprense | 26 | Ivette Joie |

| 5 | Claretta Cerio | 27 | Vittorio Vidali |

| 6 | Ilya Ehremburg | 28 | Luigi Cosenza |

| 7 | Elsa Morante | 29 | Carlo Bernari |

| 8 | Vasco Pratolini | 30 | Pietro Ingrao |

| 9 | Giulio Einaudi | 31 | Armando Pizzinato |

| 10 | Jorge Amado | 32 | Mario Montagnana |

| 11 | Mario Alicata | 33 | Gaetano Macchiaroli |

| 12 | Editore Gaspare Casella | 34 | Ernesto Treccani |

| 13 | Nazim Hikmet | 35 | Francesco De Martino |

| 14 | Palmiro Togliatti | 36 | Alessandro Vescia |

| 15 | Luchino Visconti | 37 | Angelo Rossi |

| 16 | Renato Caccioppoli | 38 | Giuseppe Zigaina |

| 17 | Stephen Hermlin | 39 | Gianzio Sacripante |

| 18 | Elvira Pajetta Berrini | 40 | Massimo Caprara |

| 19 | Salvatore Quasimodo | 41 | Clemente Maglietta |

| 20 | Bruno Molajoli | 42 | Lino Mezzacane |

| 21 | Carlo Levi | 43 | Gerardo Chiaromonte |

| 22 | Renato Guttuso | 44 | Giorgio Napolitano |

Los Versos del Capitán, digitized

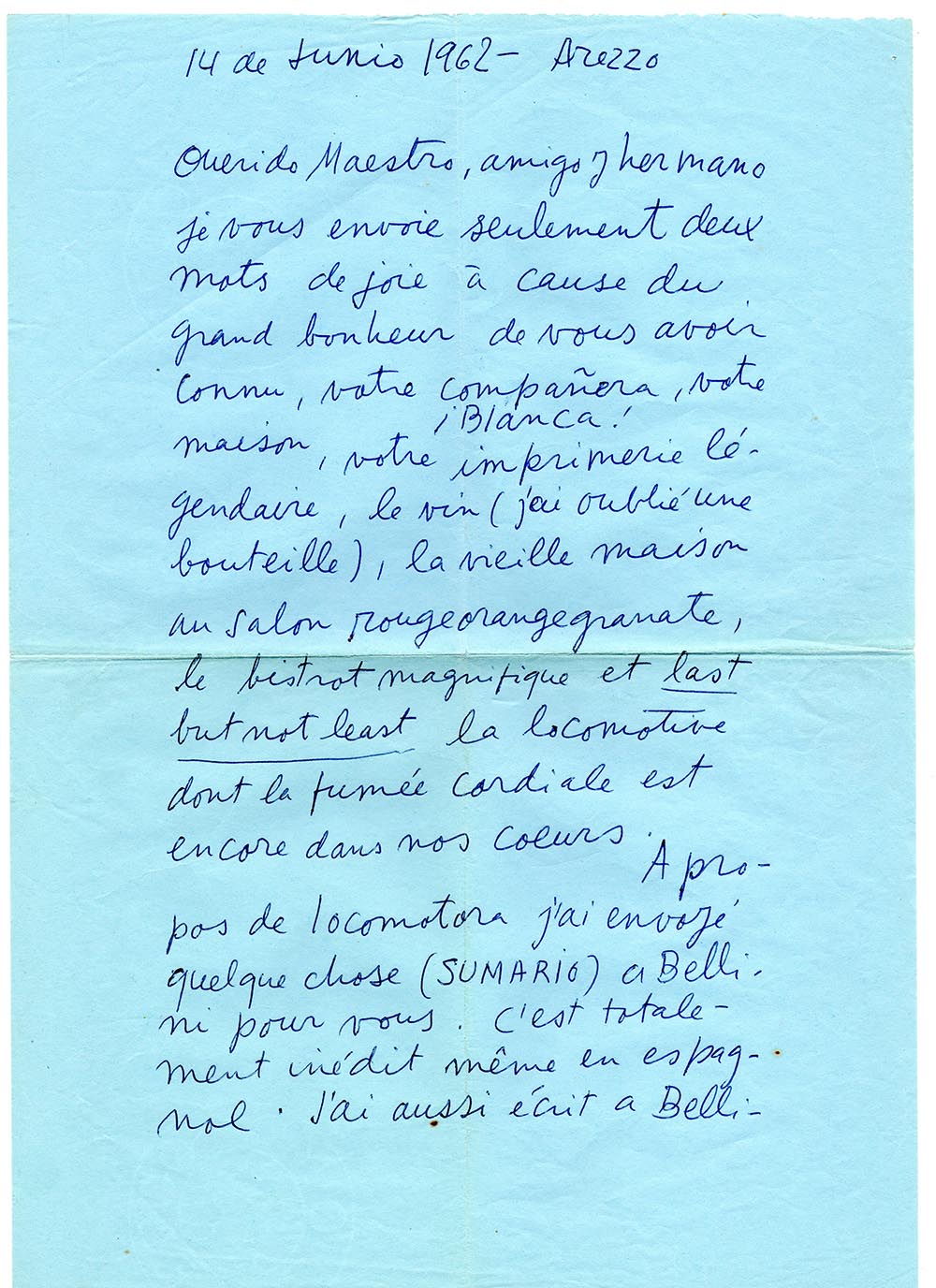

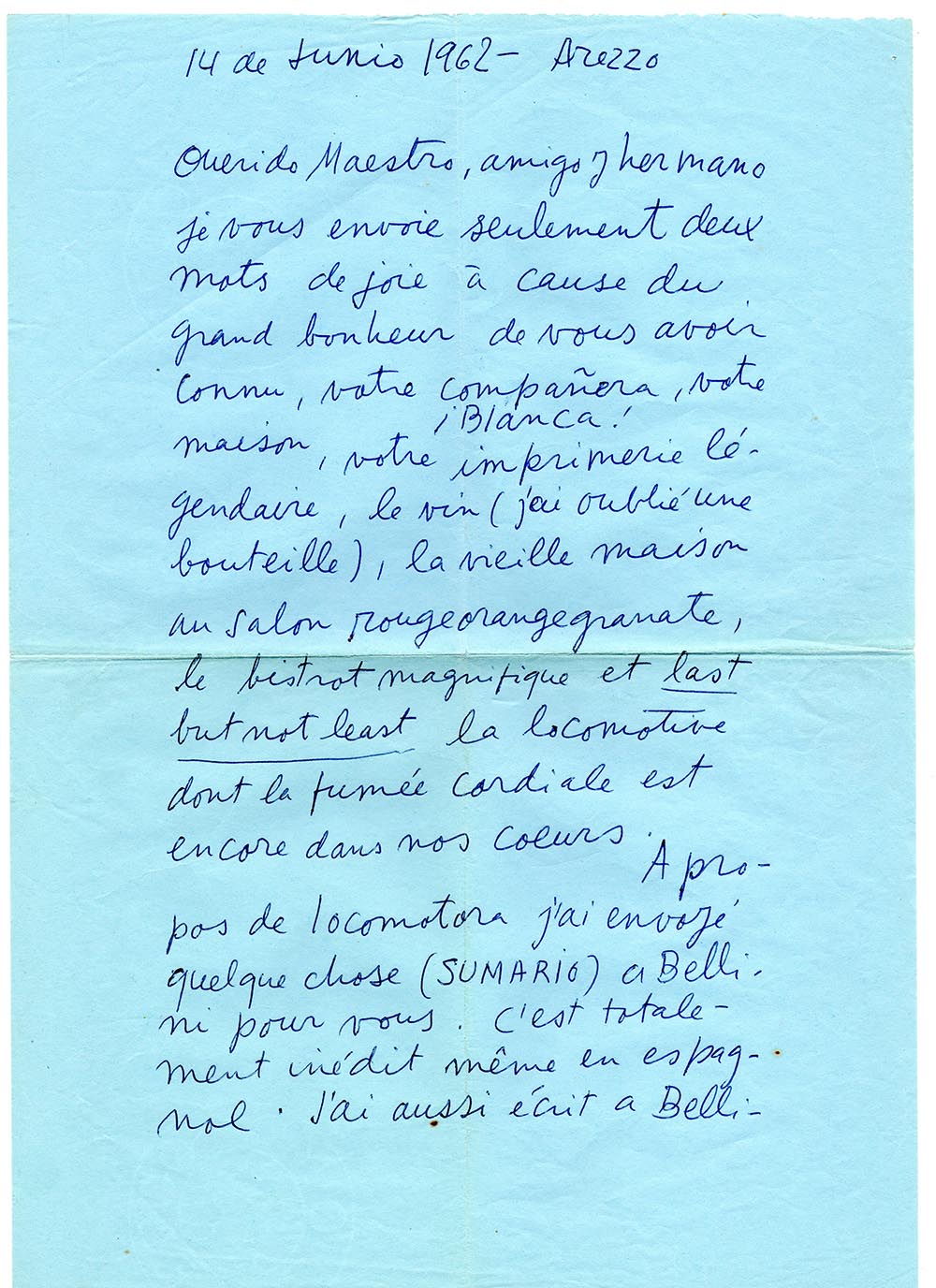

Letter from Pablo Neruda to Edwin and Claretta Cerio (July 6, 1962).

Economist, university professor, Ambassador of Chile in Italy (2000-2004), writer.

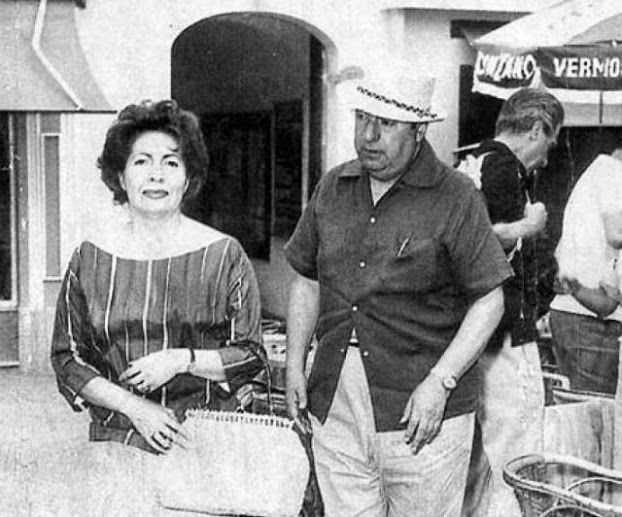

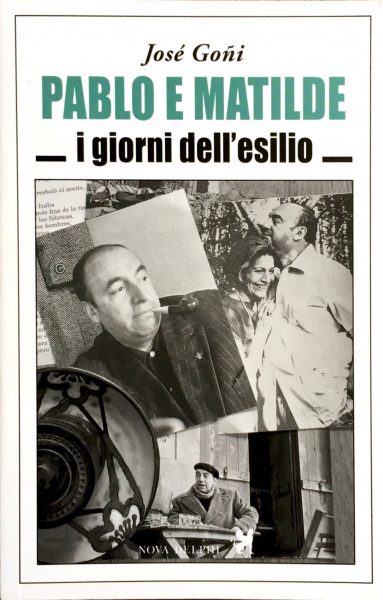

Pablo and Matilde, the days of exile. Nova Delphi Libri, Rome, Italy, 2018, 310 pages.

Pablo Neruda en Italy

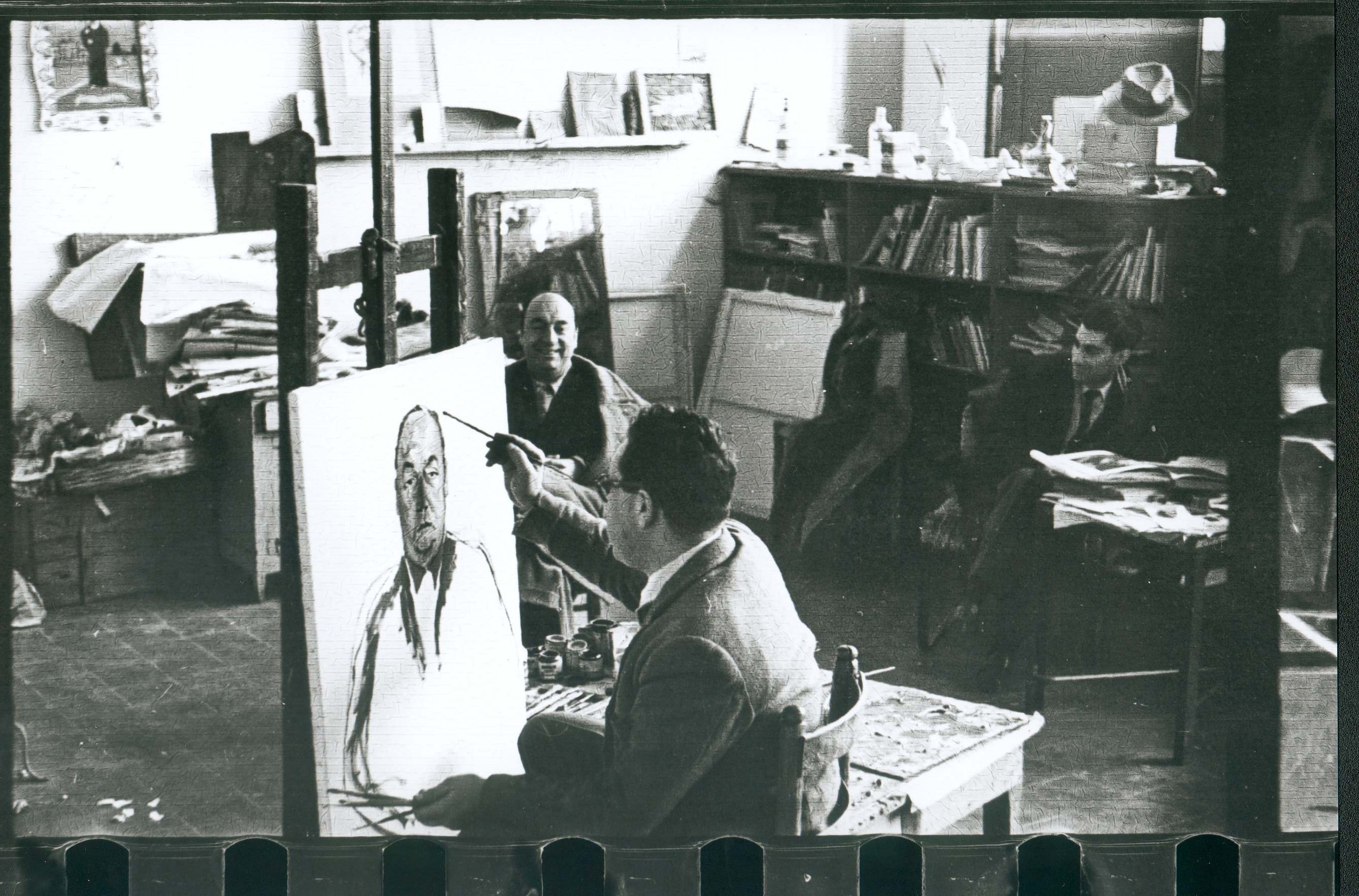

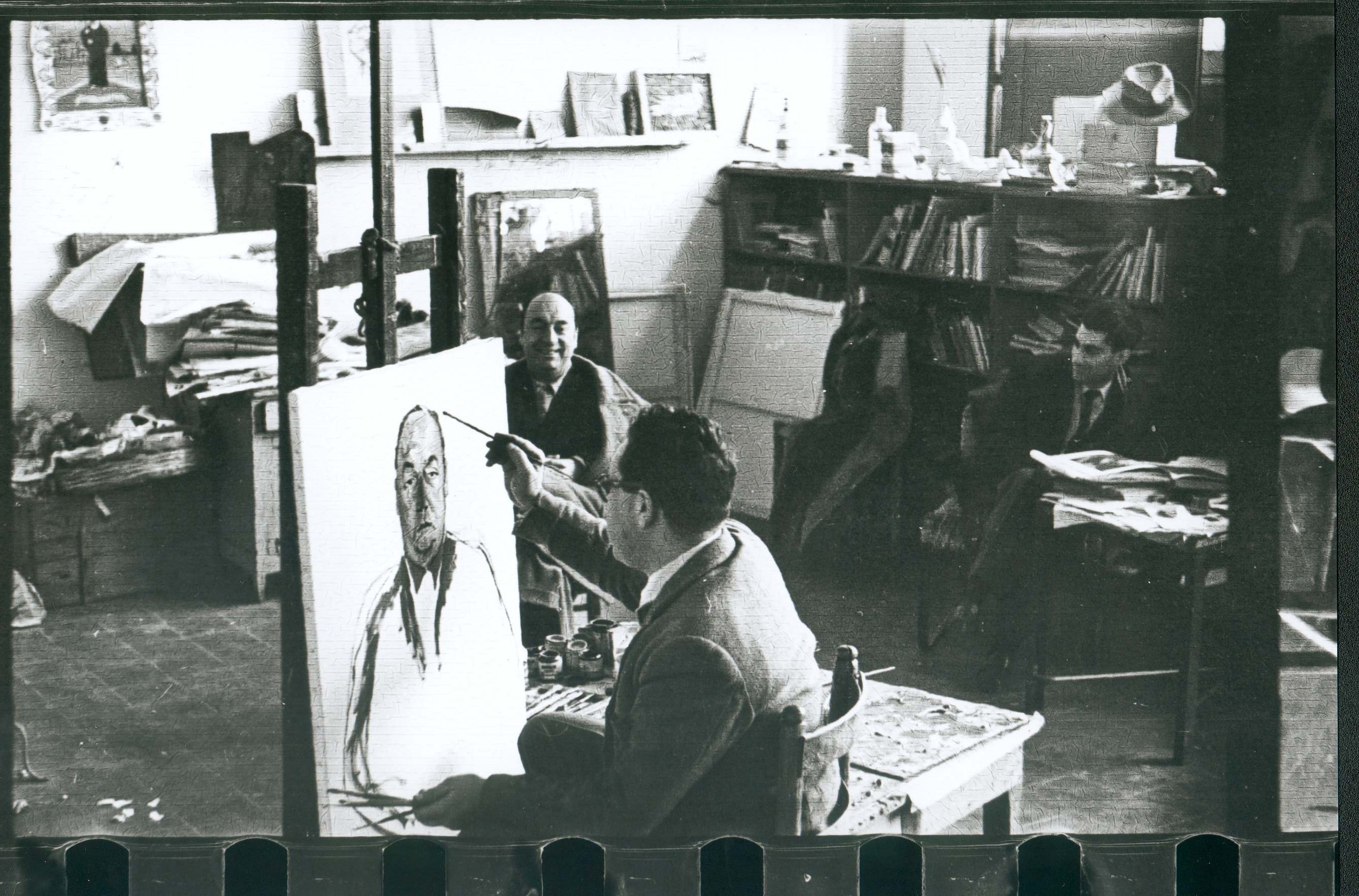

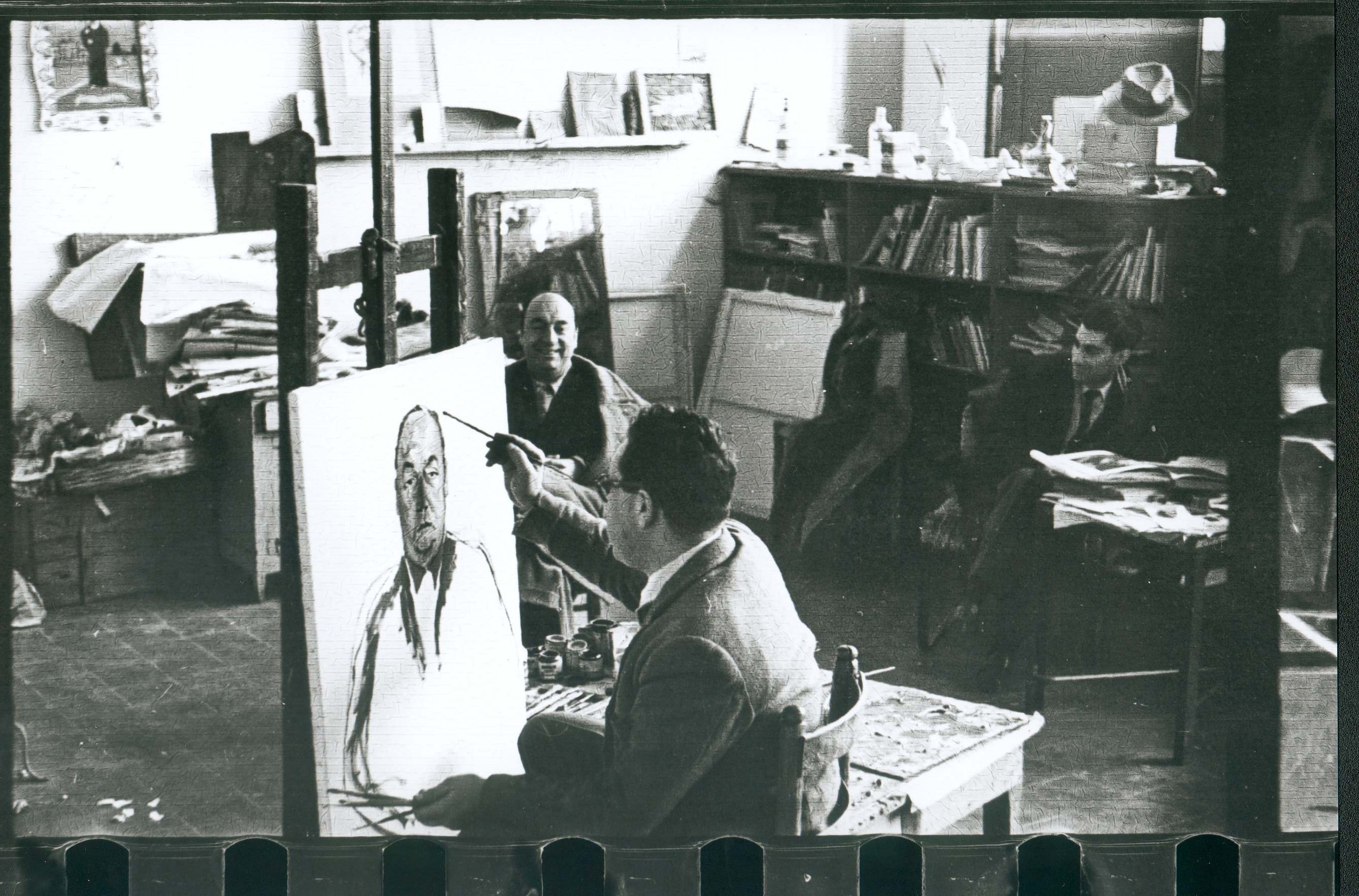

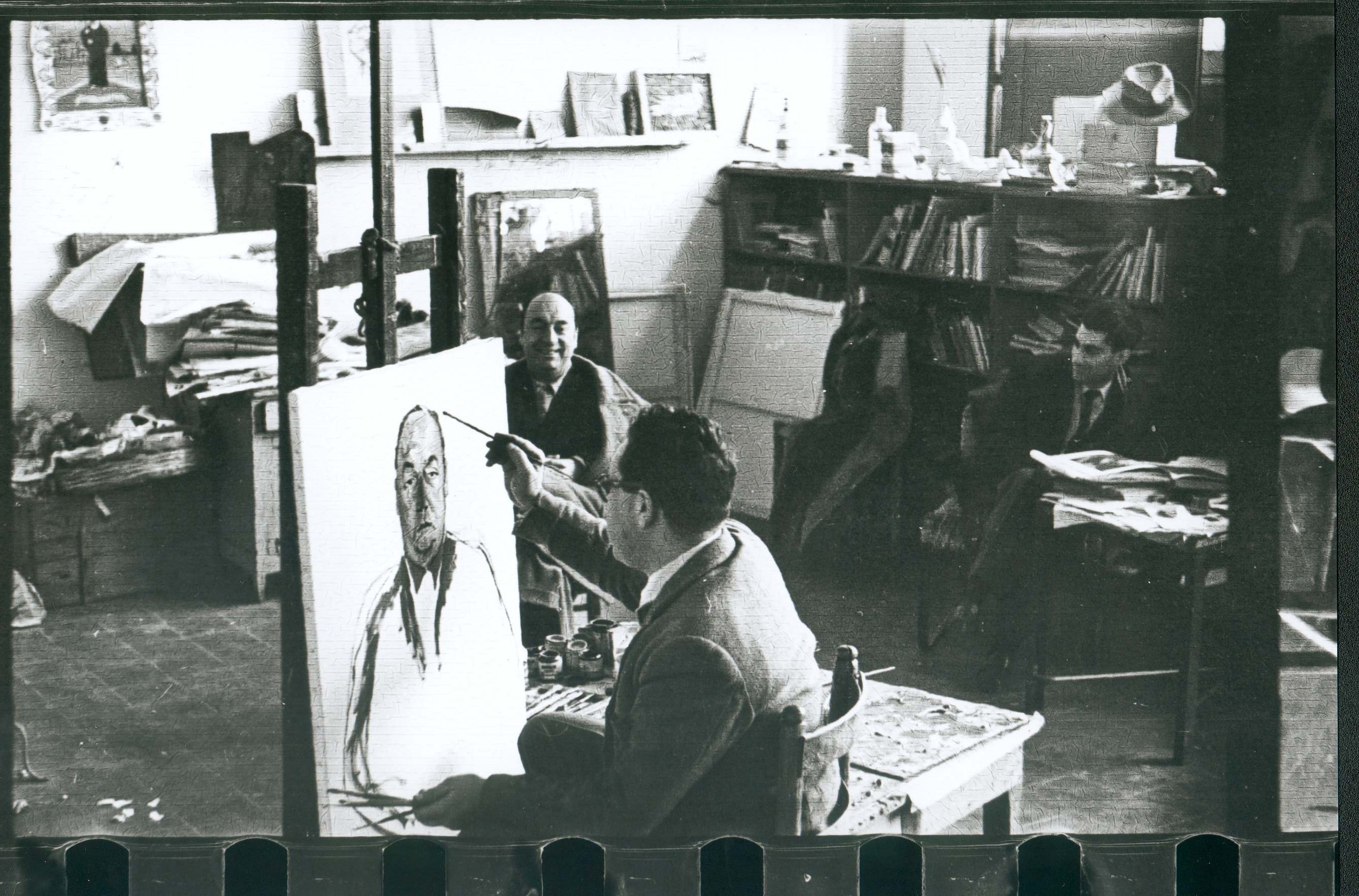

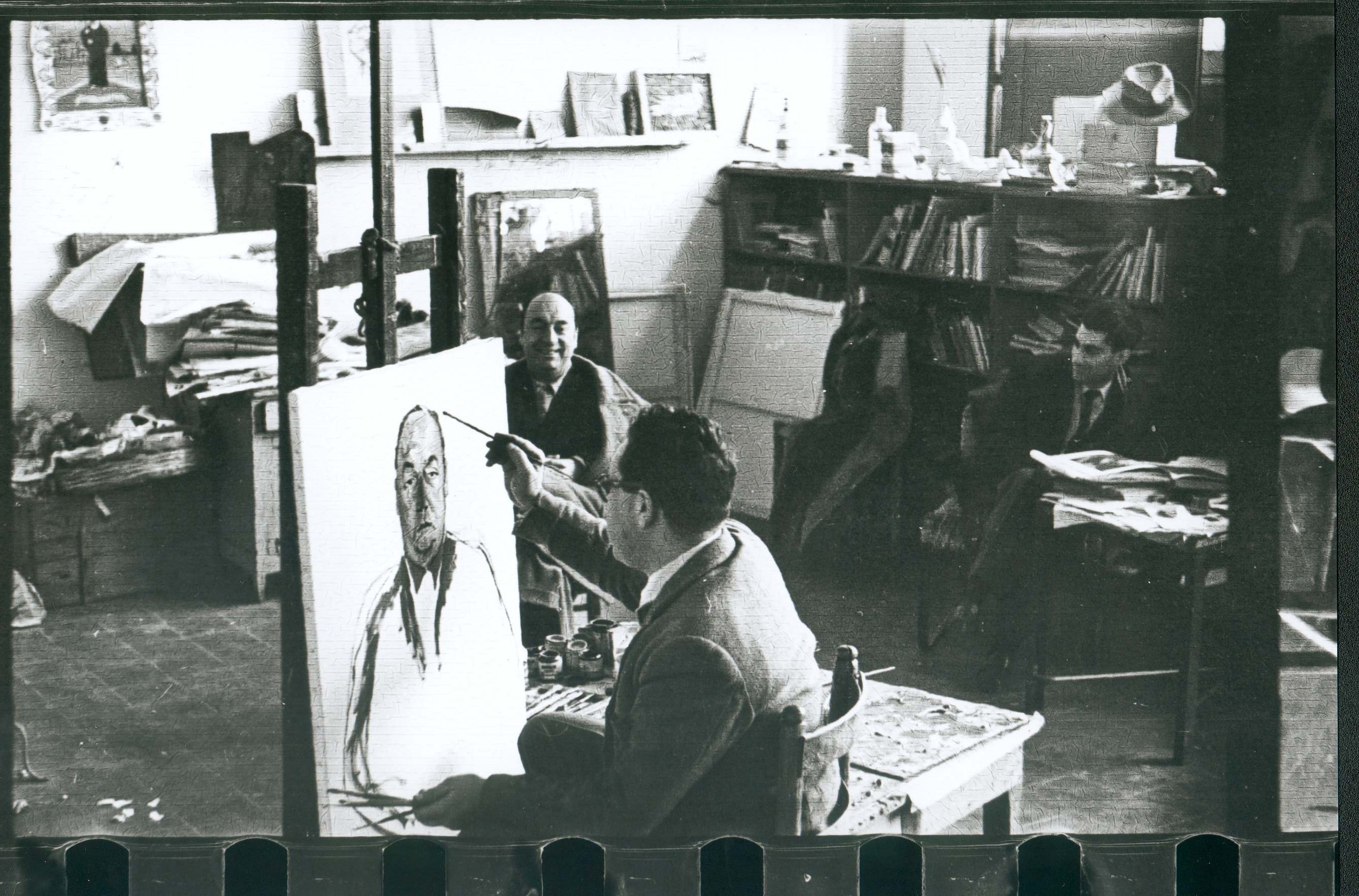

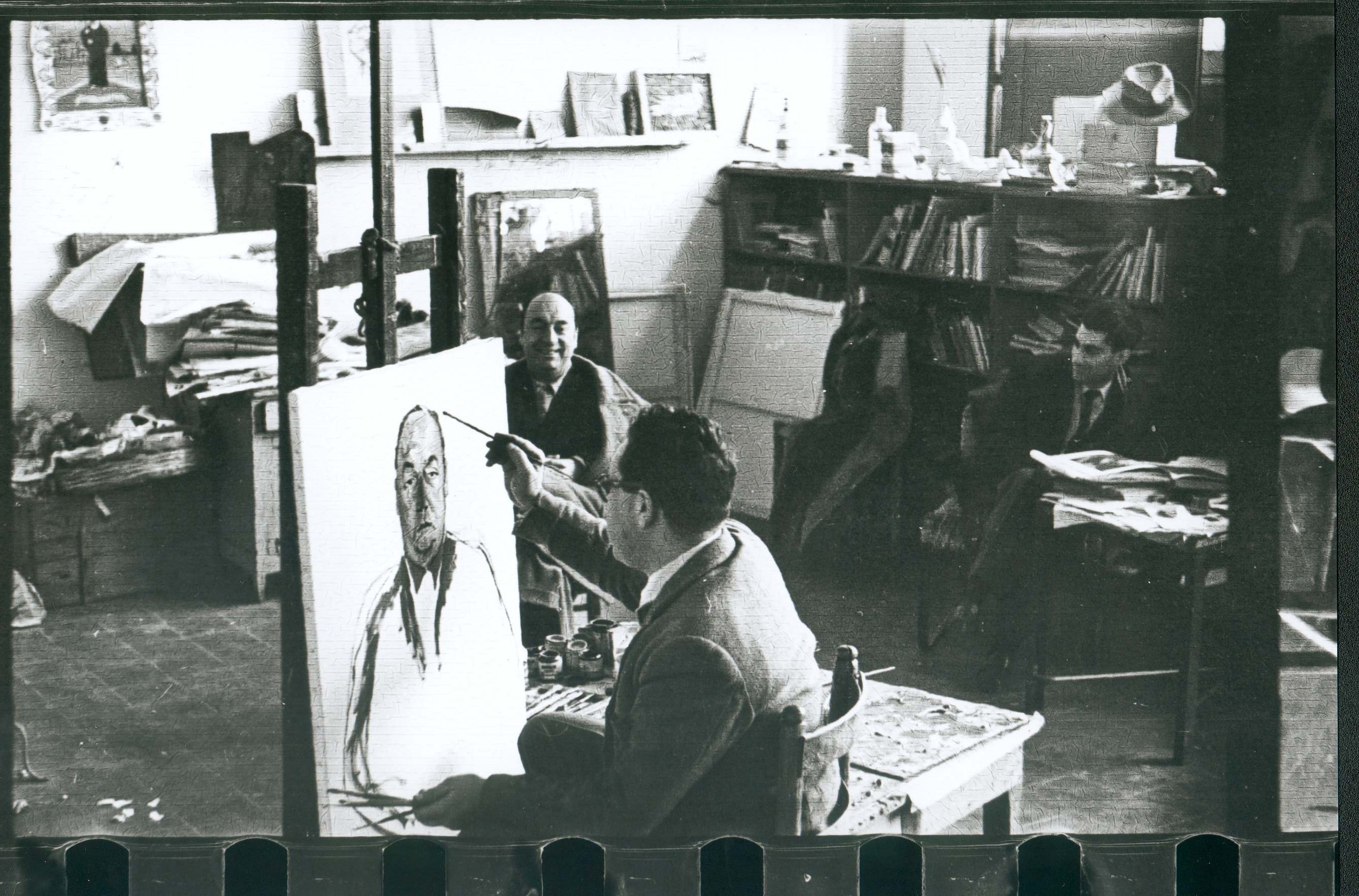

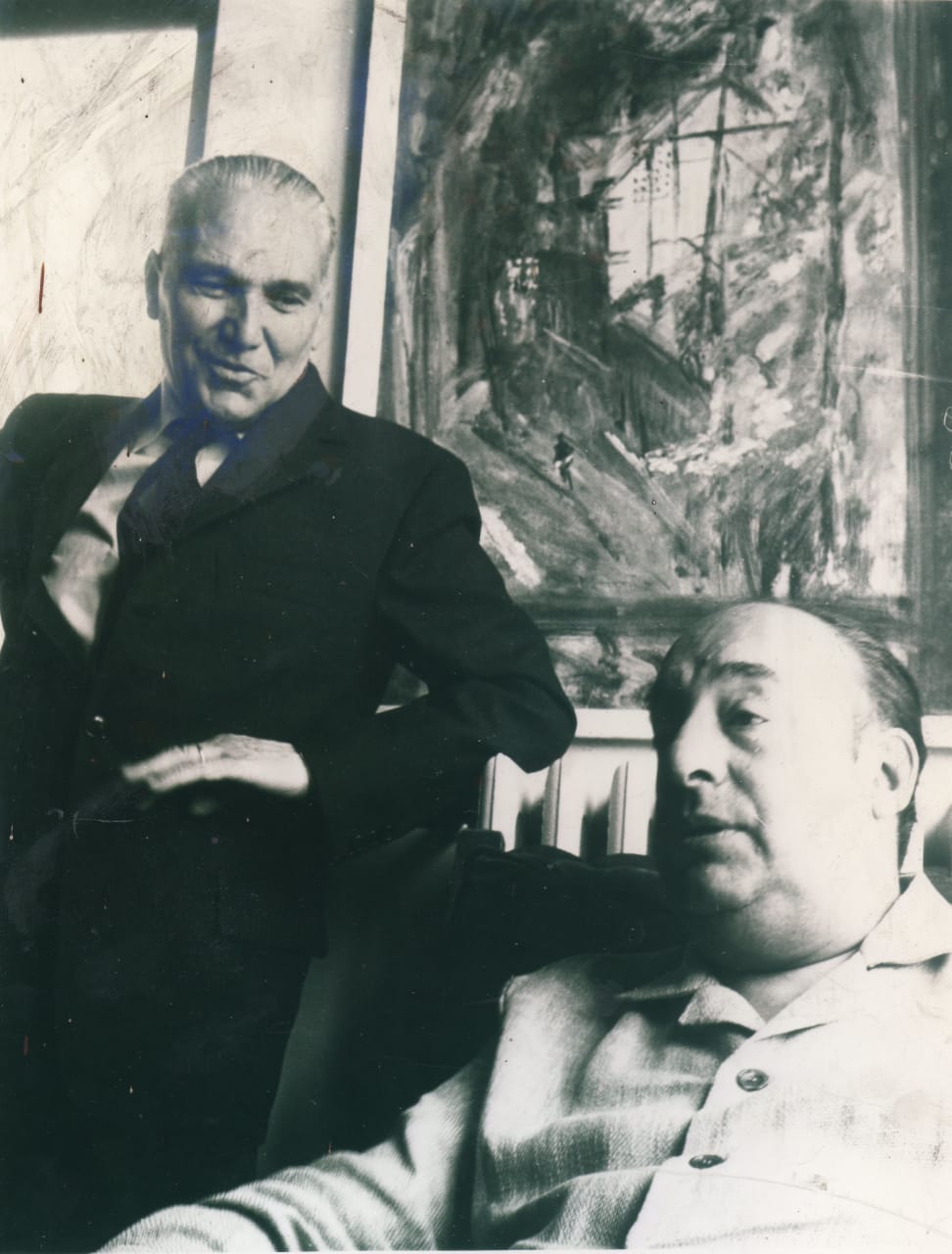

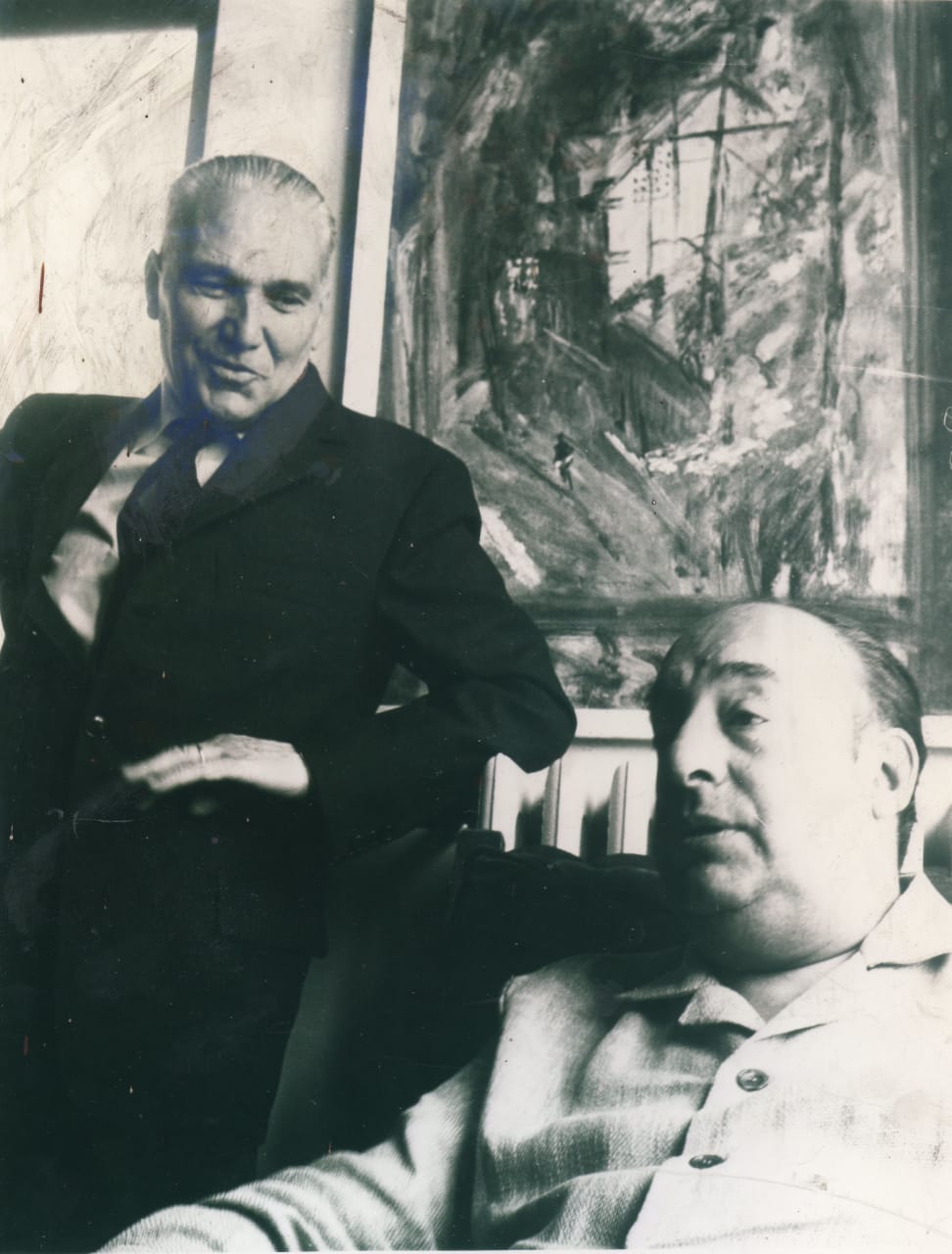

El pintor Renato Guttuso retrata en su taller a Pablo Neruda. Foto: Antonello Trombadori, periodista, crítico de arte y político, gran amigo del poeta, casado con Fulvia Trozzi (hija de Mario Trozzi, abogado y Diputado).

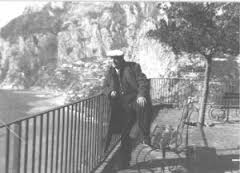

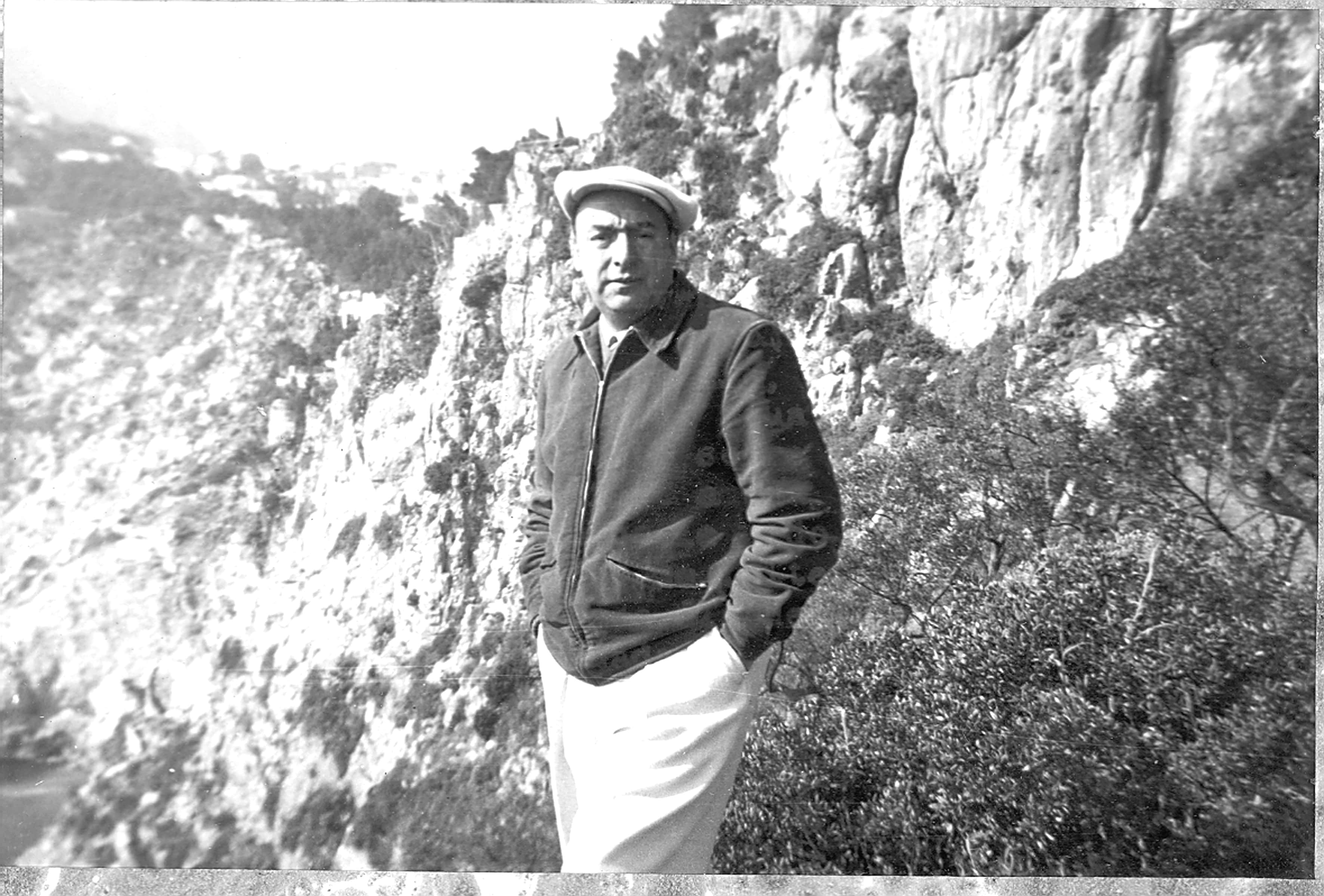

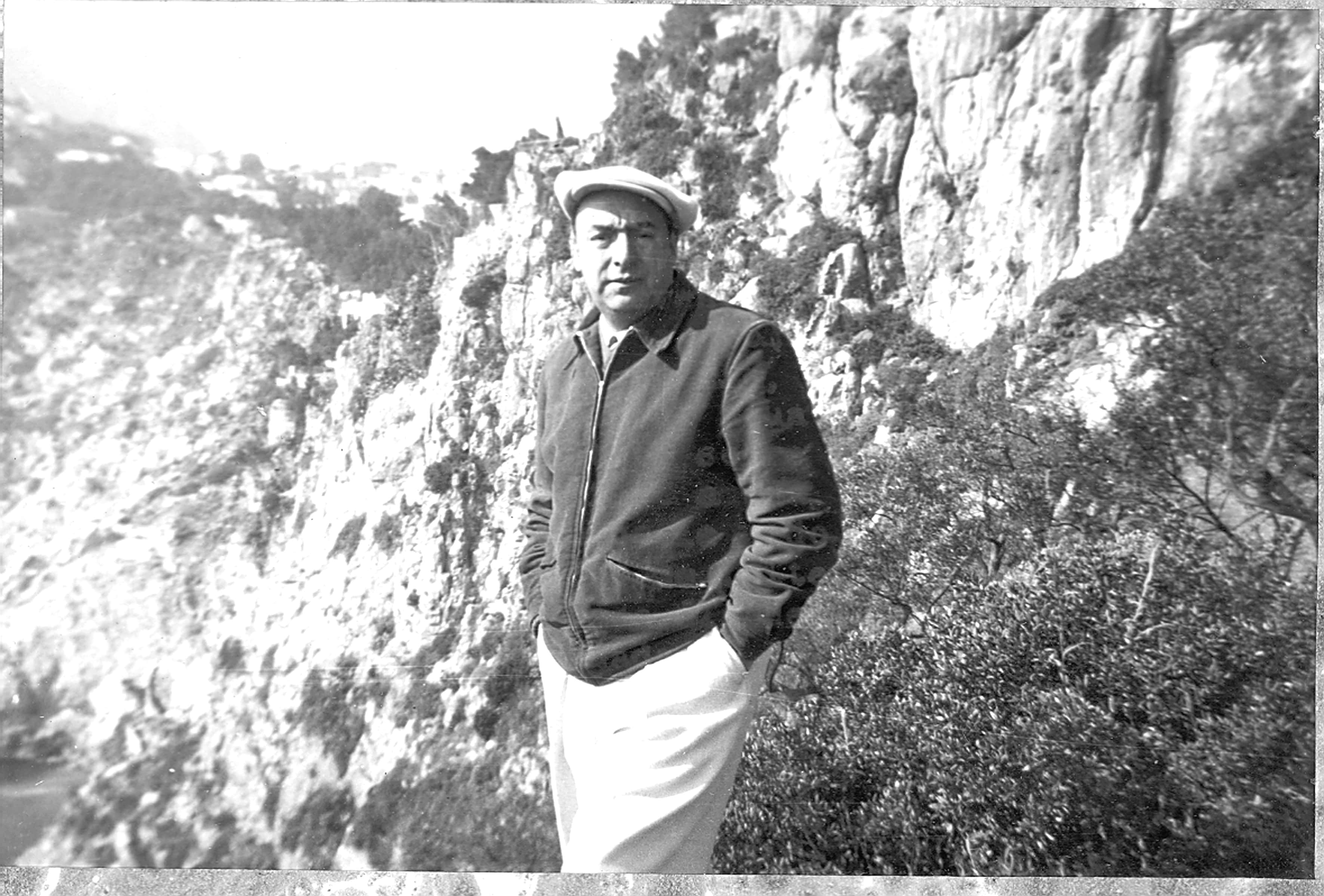

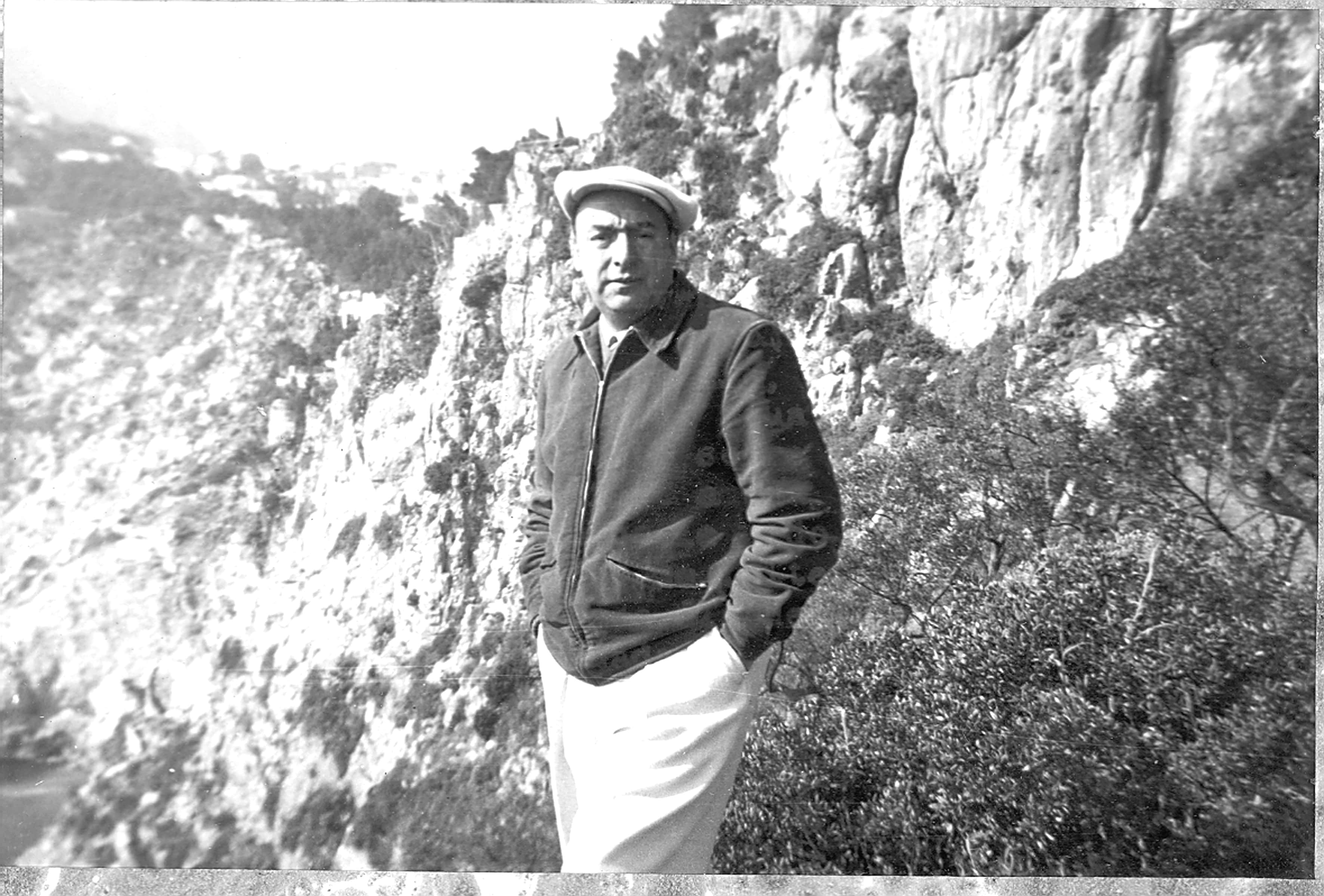

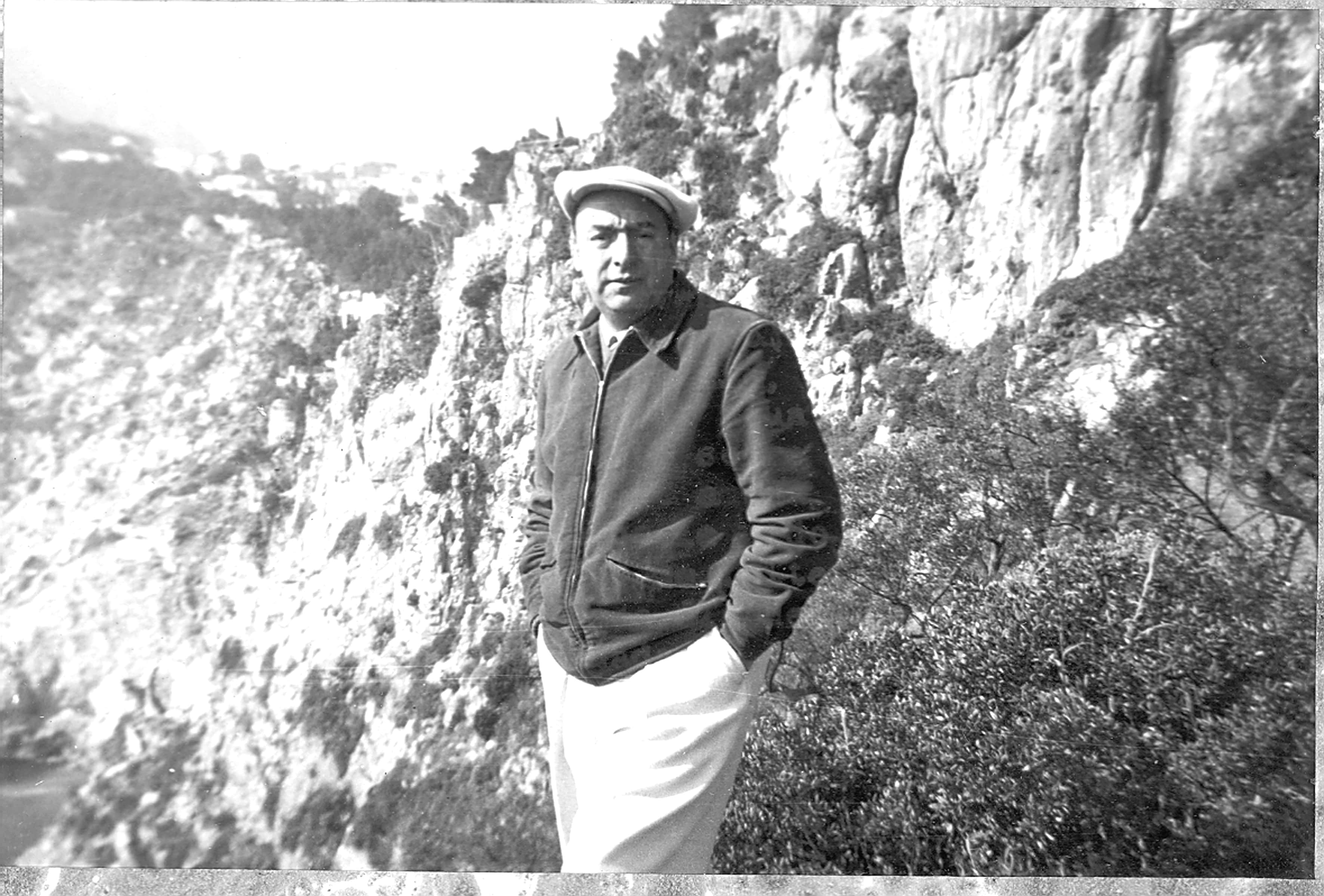

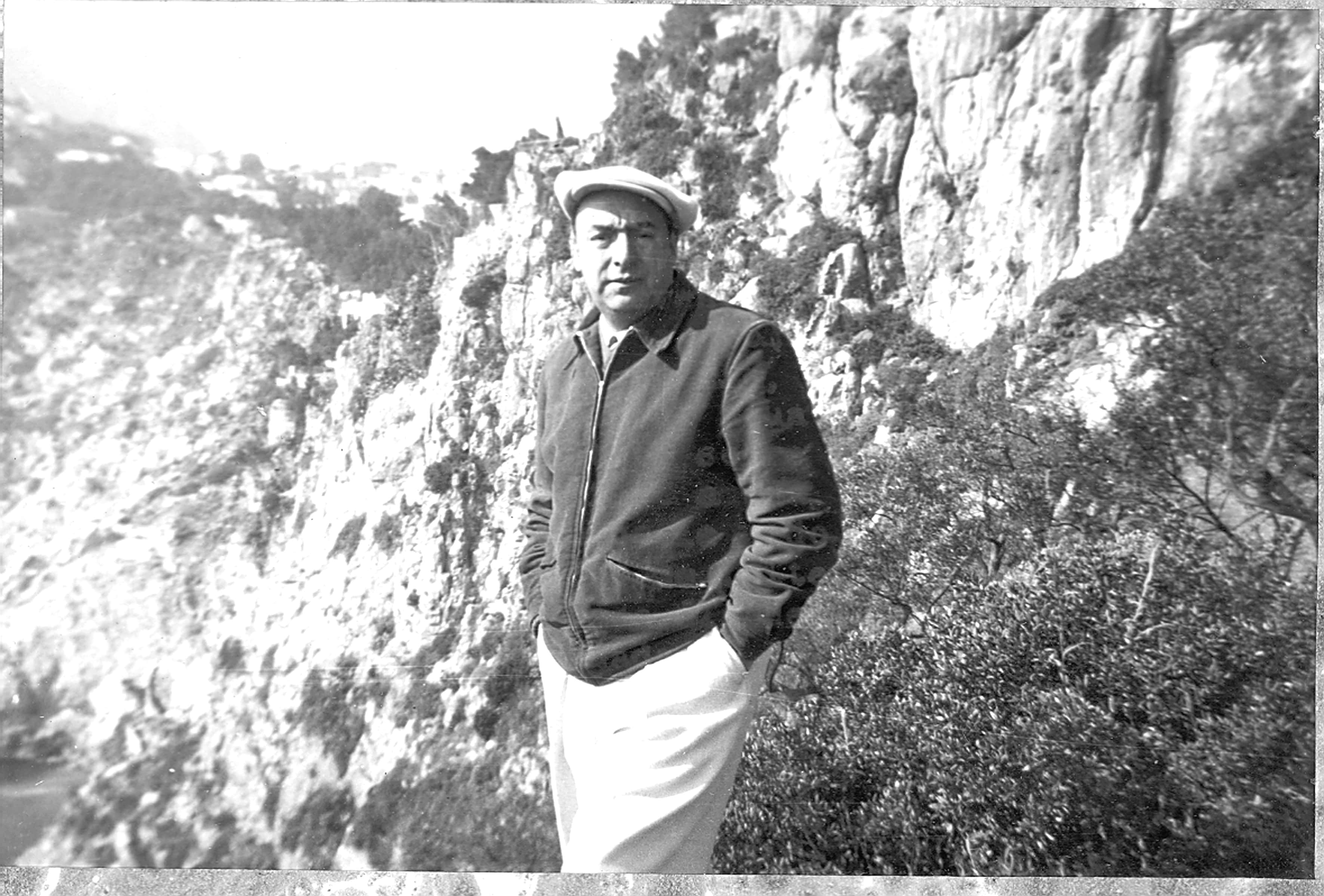

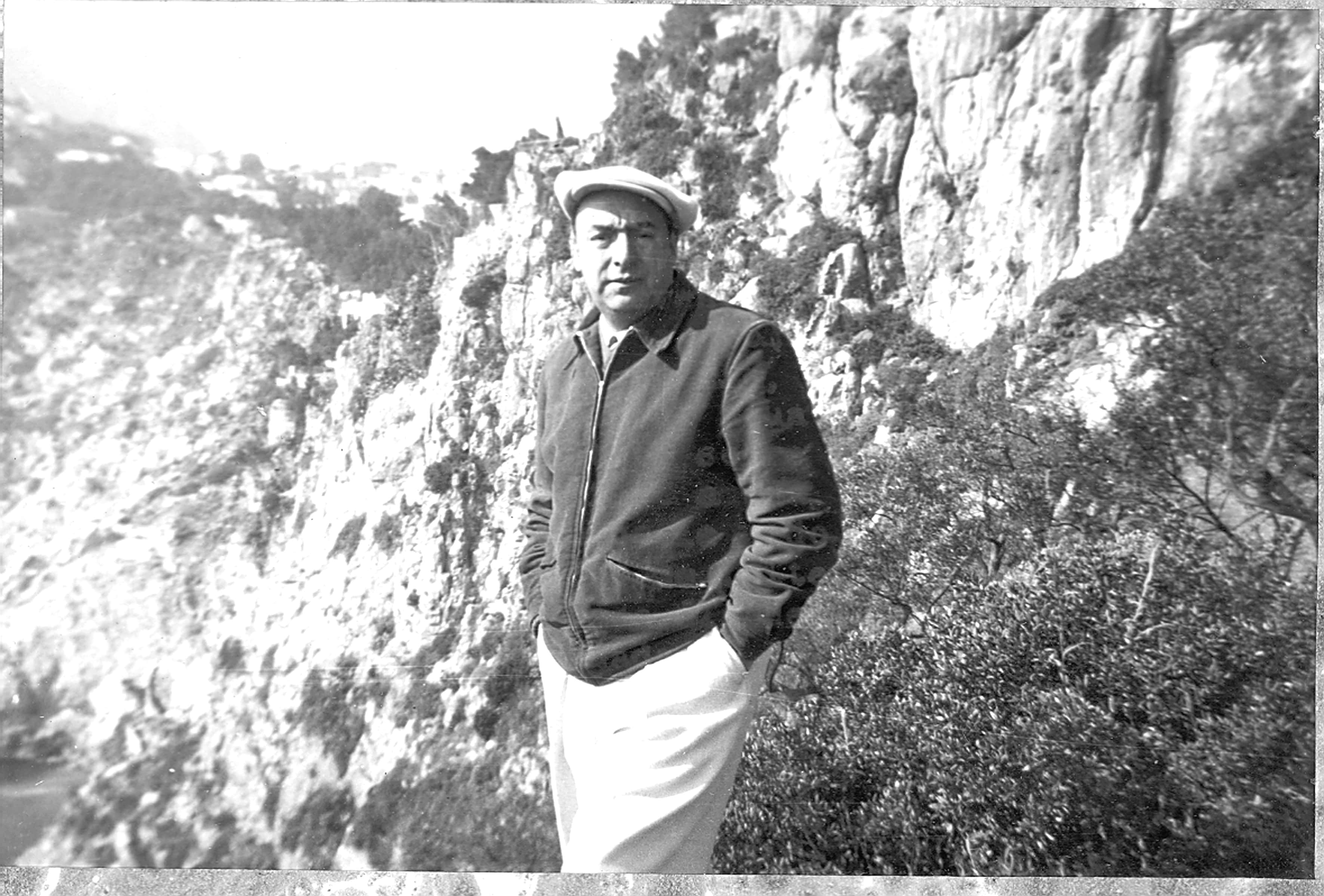

El poeta en Capri. Foto: Antonello Trombadori.

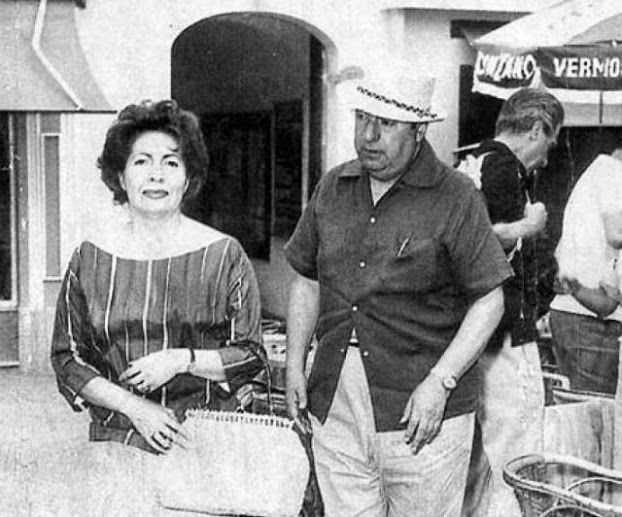

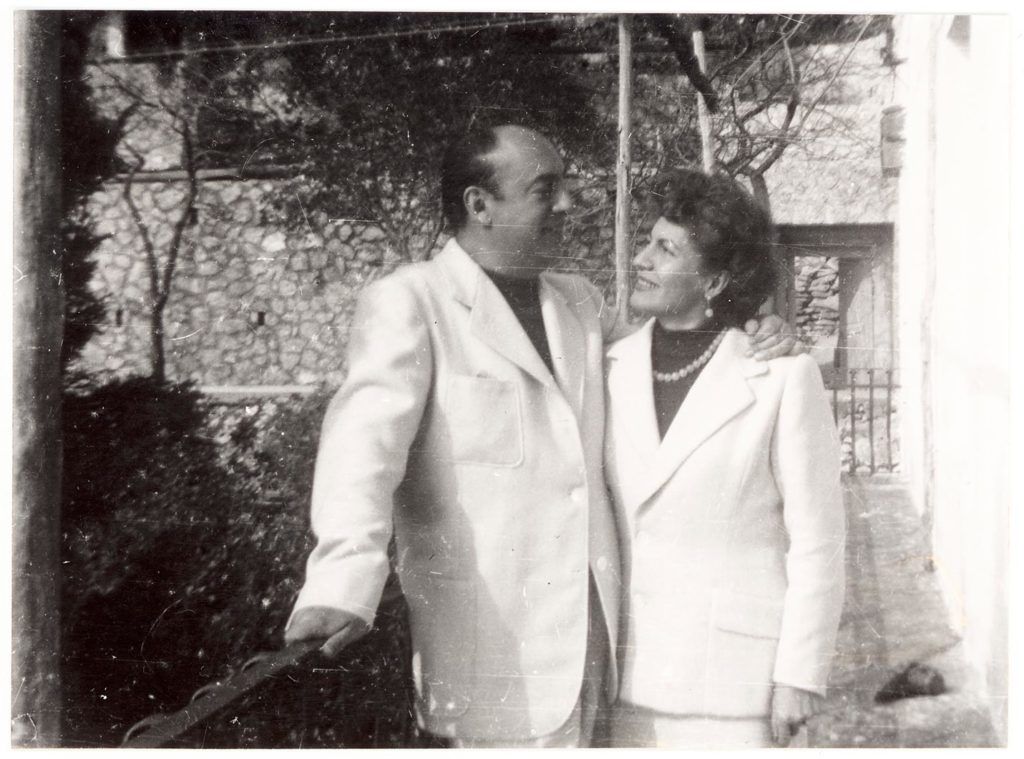

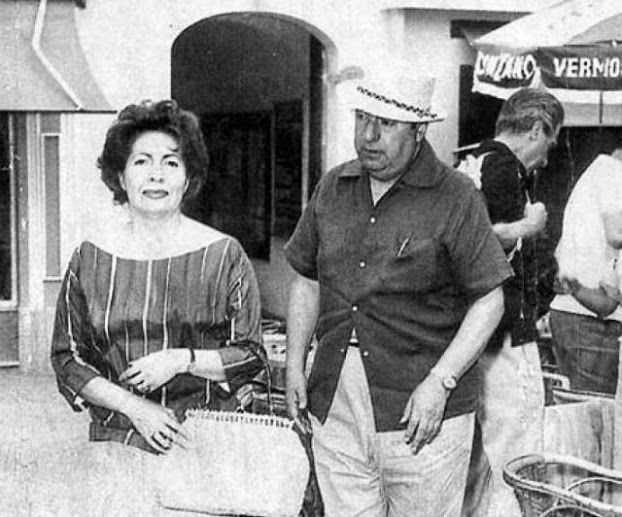

En el Hotel Belvedere, de Capri. Delia del Carril, Fulvia Trombadori y el poeta, antes de que llegara Matilde (1950-1951).

Nápoles, invierno de 1951. El poeta junto a Fulvia Trombadori y Paolo Ricci, gran amigo napolitano, pintor y crítico de arte que, en julio de 1952, editó Los Versos del Capitán, libro que fue publicado en solamente 44 ejemplares para los amigos, previa suscripción. El es quien consiguió la "Casetta d'Arturo", la casa en la cual el poeta permaneció en gran parte de su estadía en Capri, propiedad de Claretta y Edwin Cerio.

Con Fulvia Trombadori en Nápoles, invierno de 1951.

Pablo Neruda in Italia

El pintor Renato Guttuso retrata en su taller a Pablo Neruda. Foto: Antonello Trombadori, periodista, crítico de arte y político, gran amigo del poeta, casado con Fulvia Trozzi (hija de Mario Trozzi, abogado y Diputado).

El poeta en Capri. Foto: Antonello Trombadori.

En el Hotel Belvedere, de Capri. Delia del Carril, Fulvia Trombadori y el poeta, antes de que llegara Matilde (1950-1951).

Nápoles, invierno de 1951. El poeta junto a Fulvia Trombadori y Paolo Ricci, gran amigo napolitano, pintor y crítico de arte que, en julio de 1952, editó Los Versos del Capitán, libro que fue publicado en solamente 44 ejemplares para los amigos, previa suscripción. El es quien consiguió la "Casetta d'Arturo", la casa en la cual el poeta permaneció en gran parte de su estadía en Capri, propiedad de Claretta y Edwin Cerio.

Con Fulvia Trombadori en Nápoles, invierno de 1951.

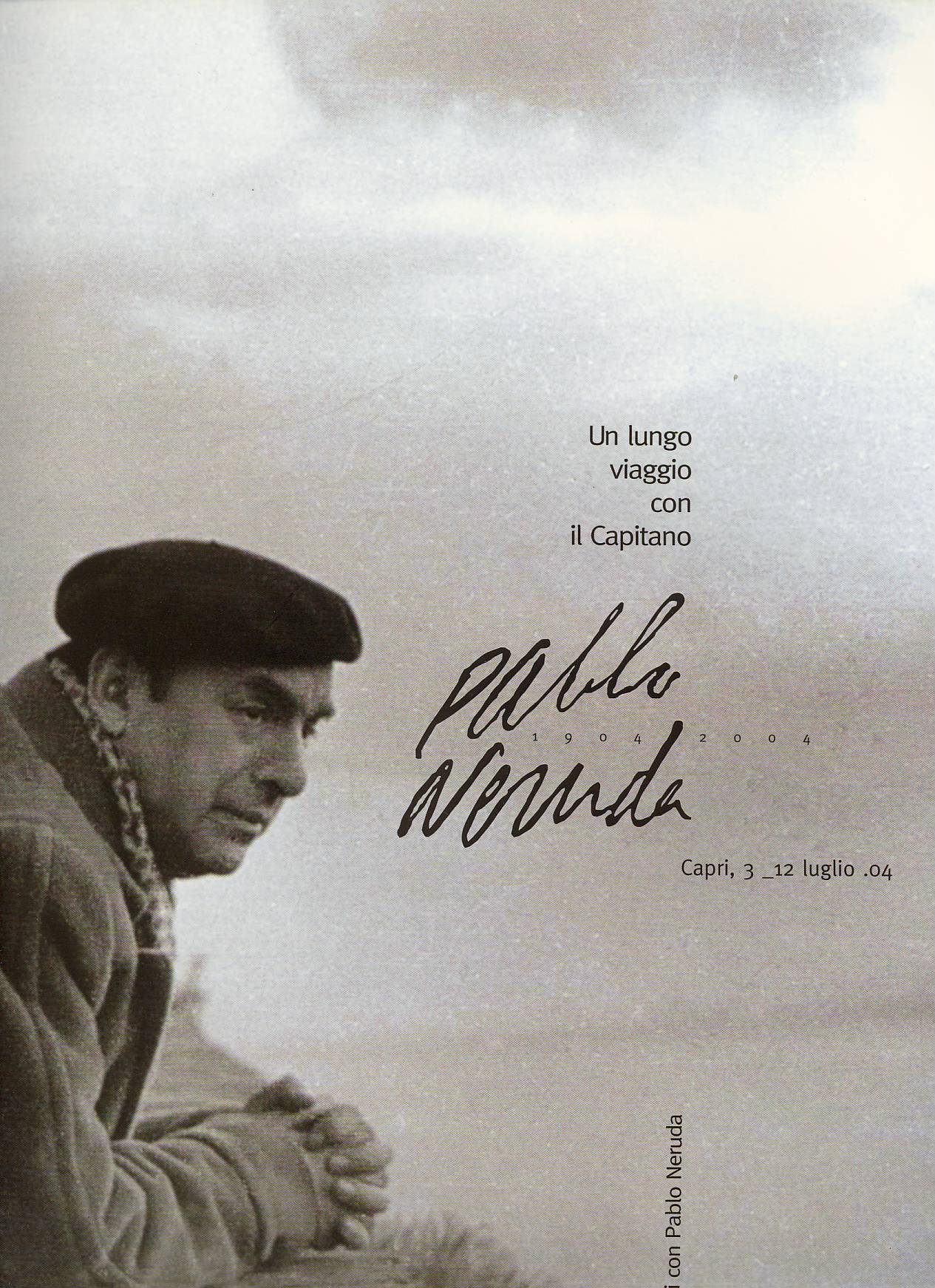

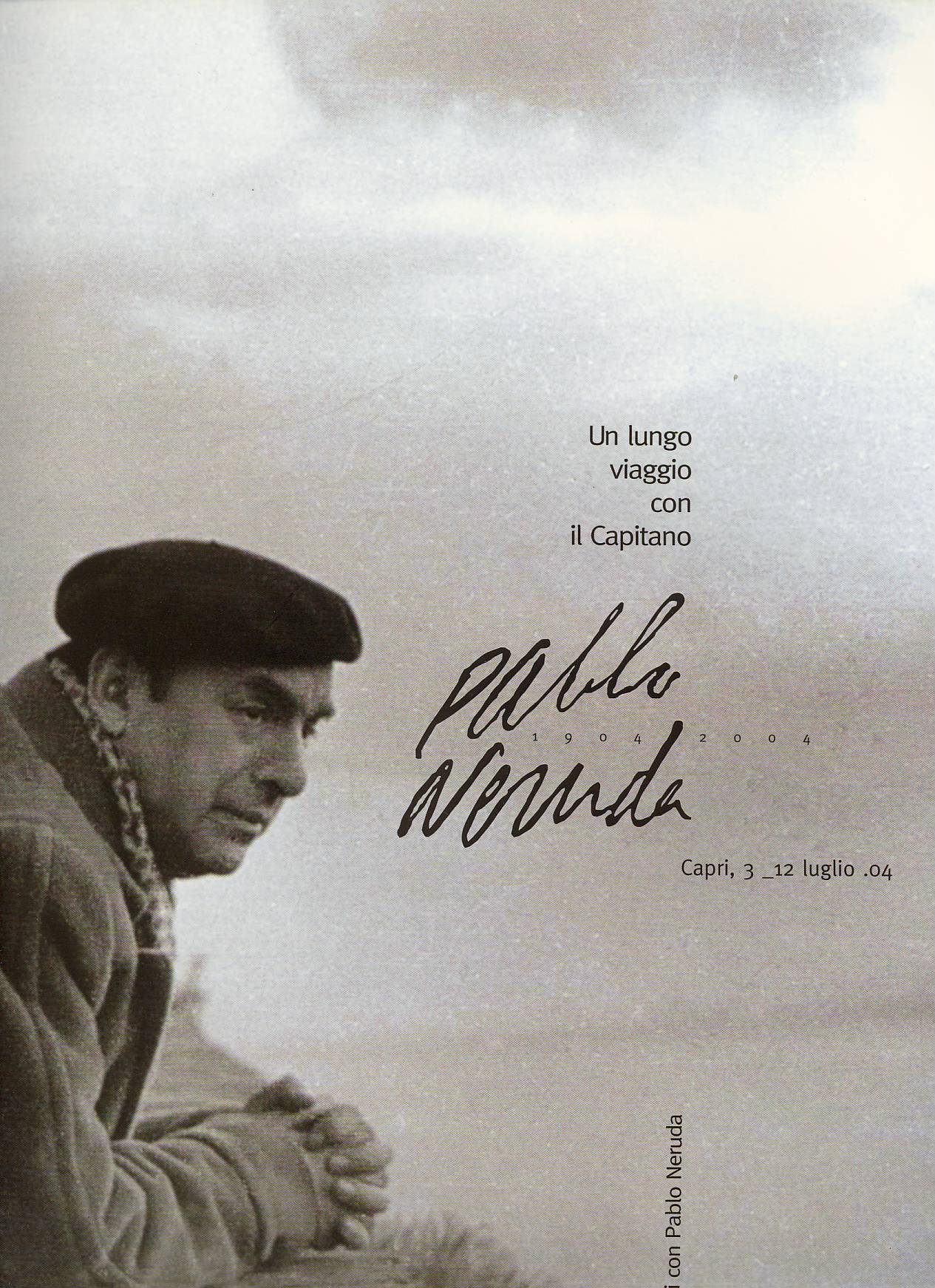

Un largo viaje con el Capitán. Capri, 2004.

Poster del evento cultural "Un largo viaje con el capitán", realizado en Capri, del 6 al 12 de julio de 2004.

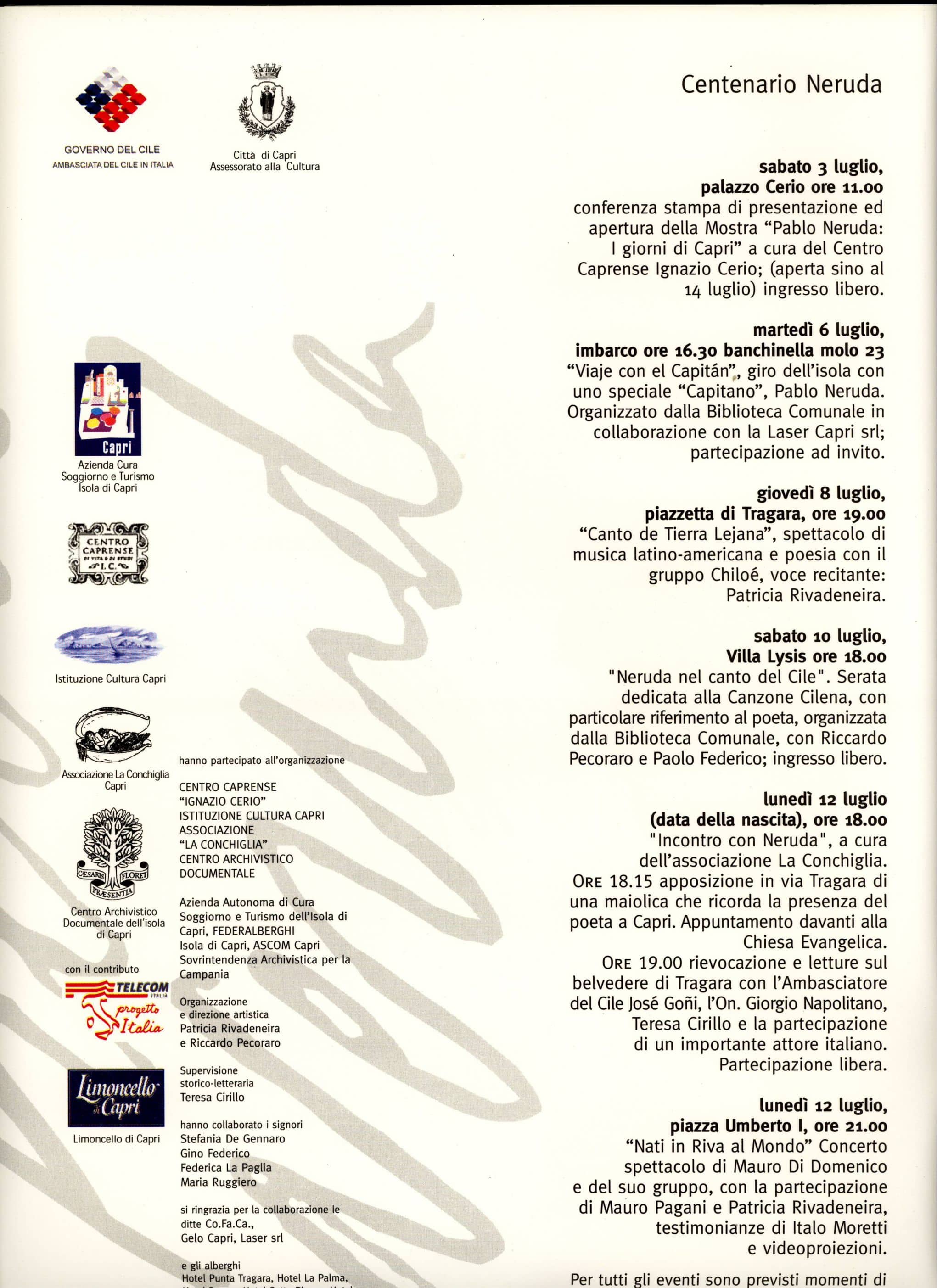

Programa de las actividades culturales realizadas en Capri, durante la semana dedicada a Pablo Neruda en 2004, con motivo del centenario de su nacimiento.

Bandera chilena en Via Tragara, donde vivió Pablo Neruda a comienzos de la década del 50.

El Alcalde de Capri, se dirige a los invitados a la ceremonia. Junto a él, se encuentra el Asesor de Cultura de la Municipalidad de Capri.

El señor Embajador de Chile en Italia José Goñi, la Agregada Cultural de Chile en Italia Patricia Rivadeneira, Fulvia Trombadori y Giorgio Napolitano, actualmente Senador Vitalicio, fue Presidente de la Cámara de Diputados, Ministro del Interior y Presidente de la República de Italia (2006-2015). También fue amigo de Neruda y uno de los 44 propietarios de Los Versos del Capitán.

El Embajador de Chile en Italia José Goñi y Fulvia Trombadori, durante el evento cultural dedicado a Neruda.

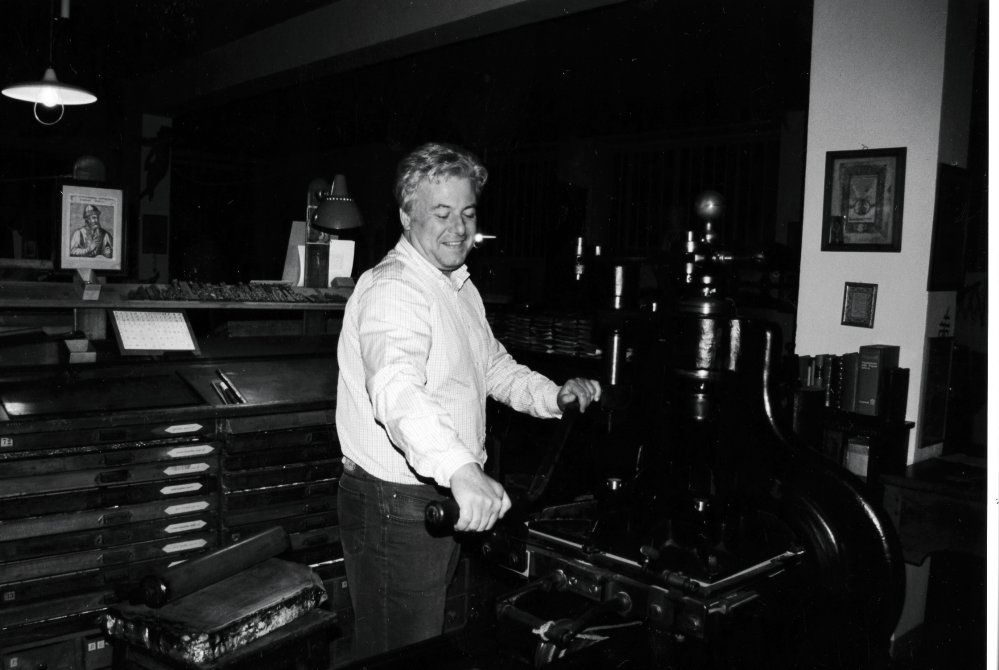

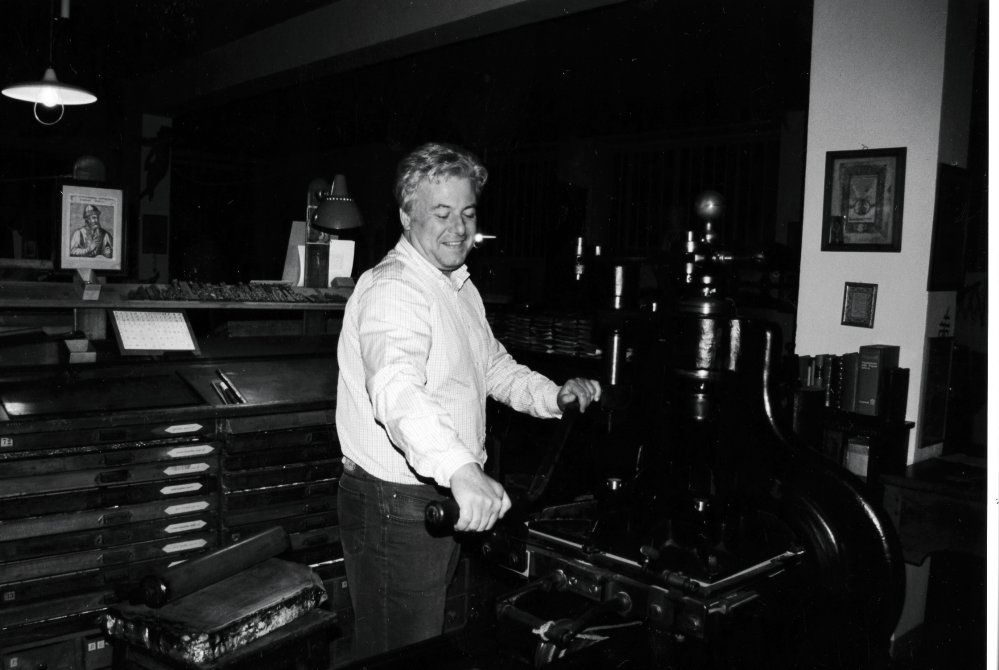

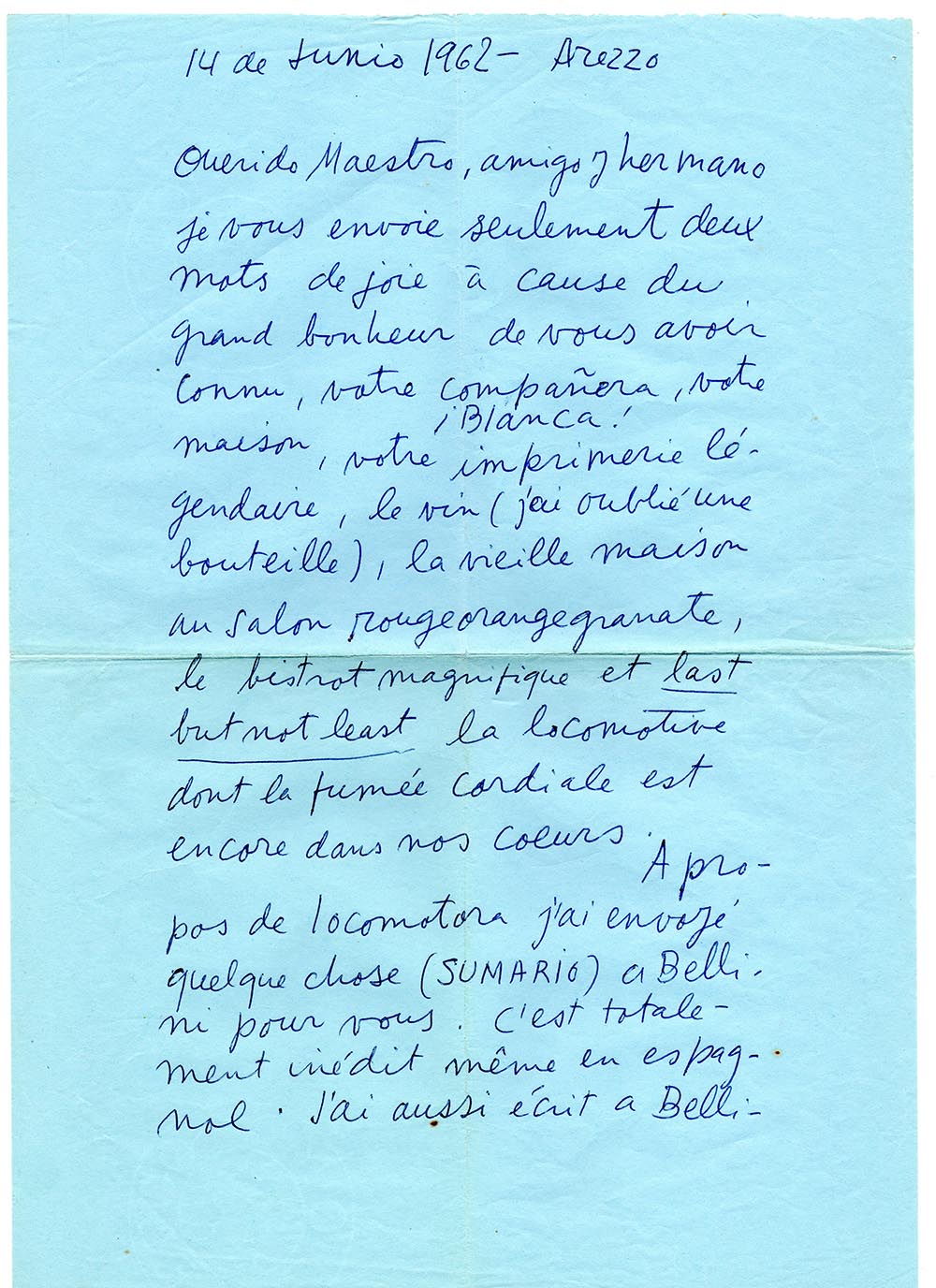

Visit Enrico Tallone and his mother, Bianca Bianconi.

Locomotora en Alpignano.

Enrico Tallone y José Goñi, Embajador de Chile en Italia en aquella época (2000-2004).

El Embajador de Chile en Italia (2000-2004) José Goñi, con Enrico Tallone.

El Embajador de Chile en Italia (2000-2004) José Goñi, con Bianca Tallone.

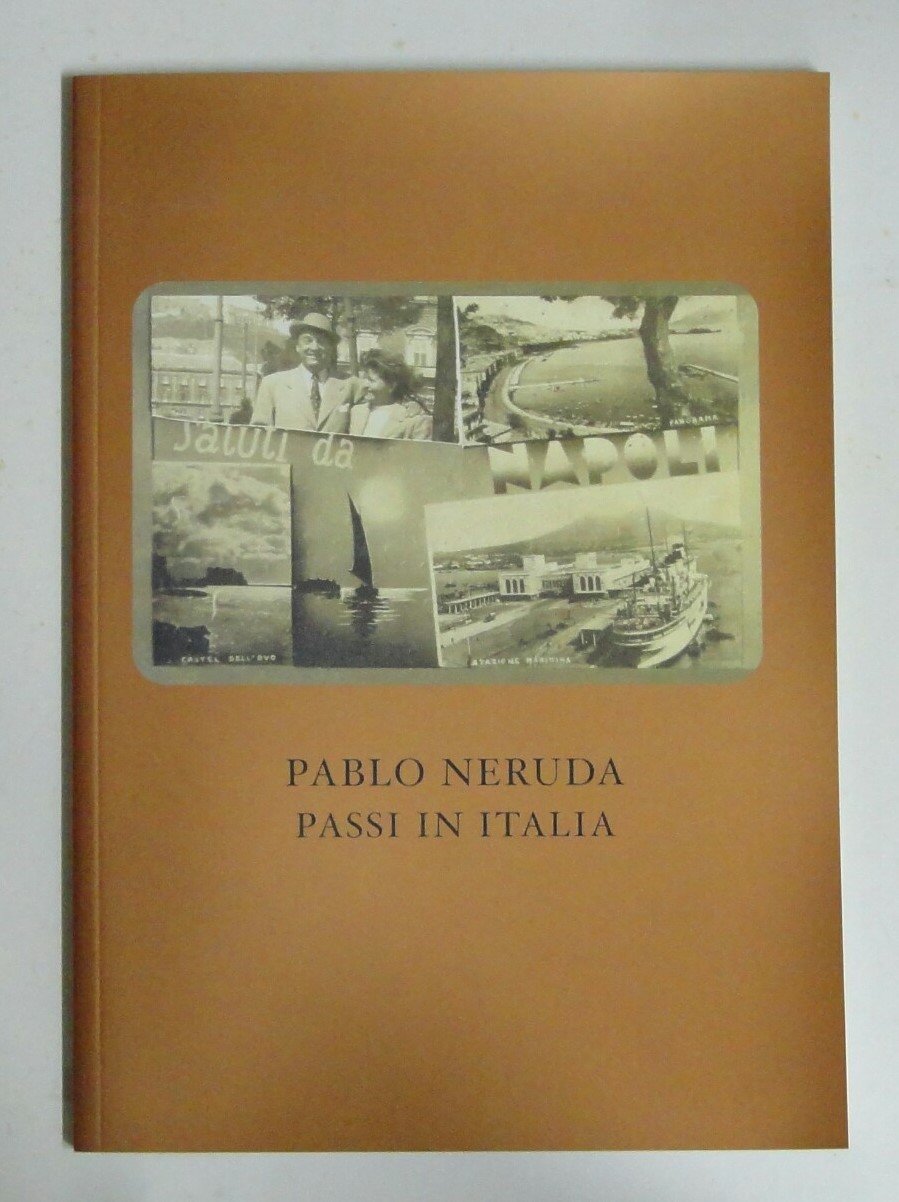

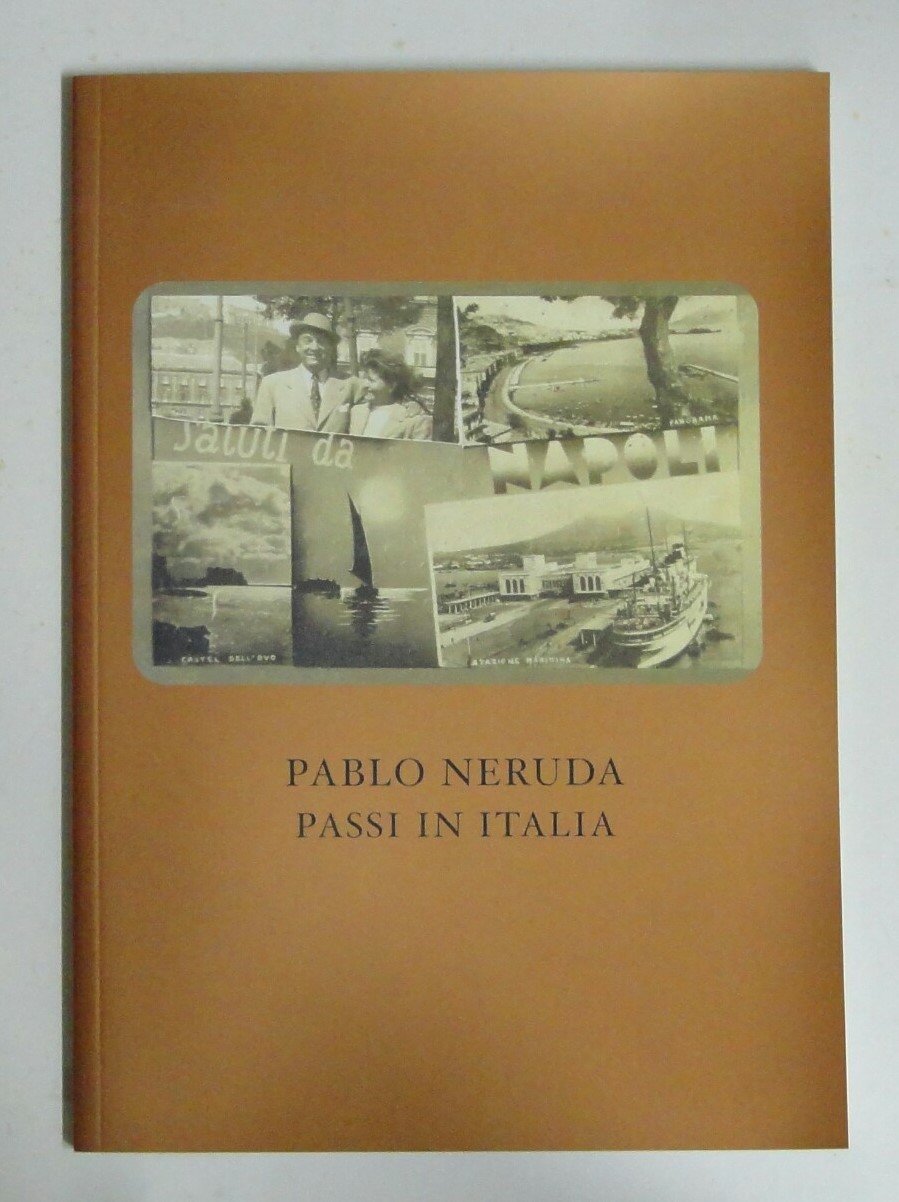

Libro Pablo Neruda. Passi in Italia.

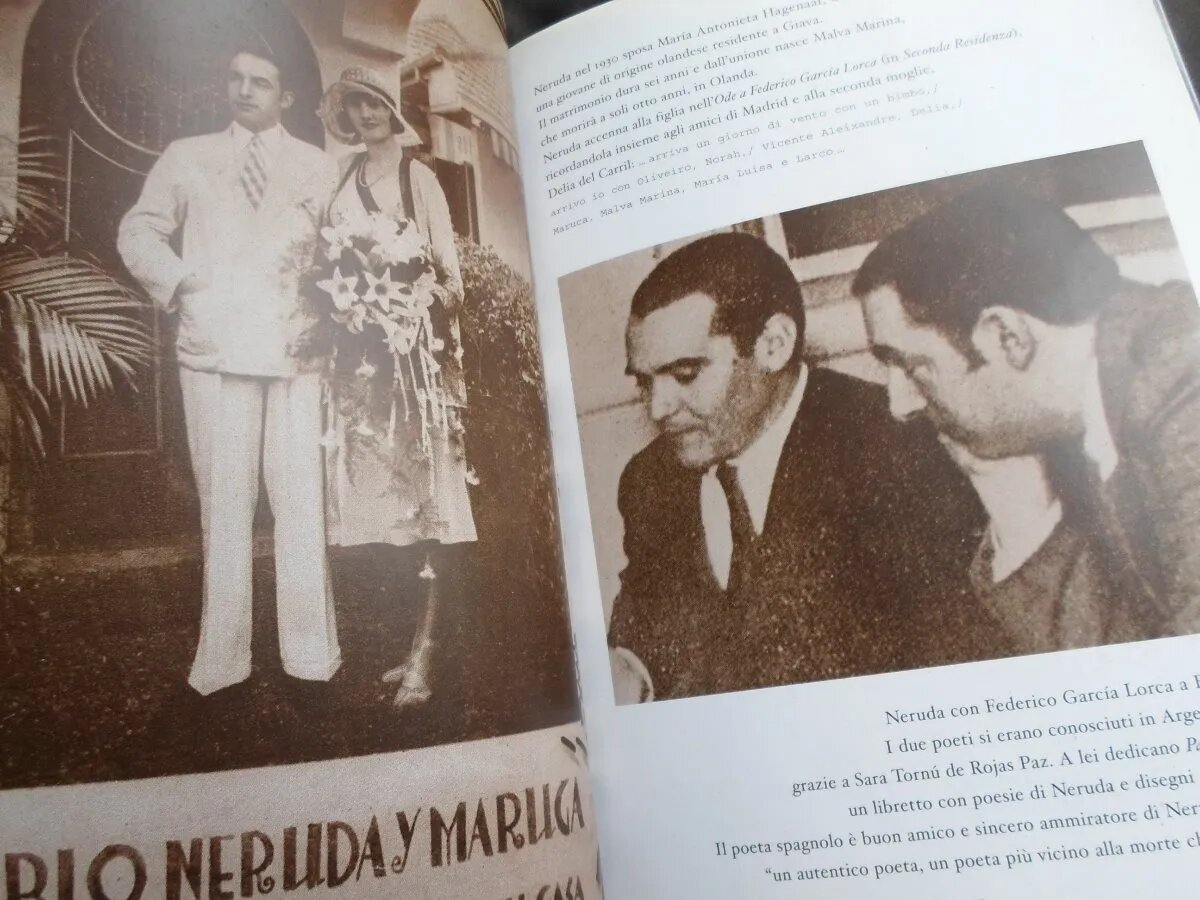

Portada del libro.

Libro publicado en Roma el año 2004

Interior del libro.

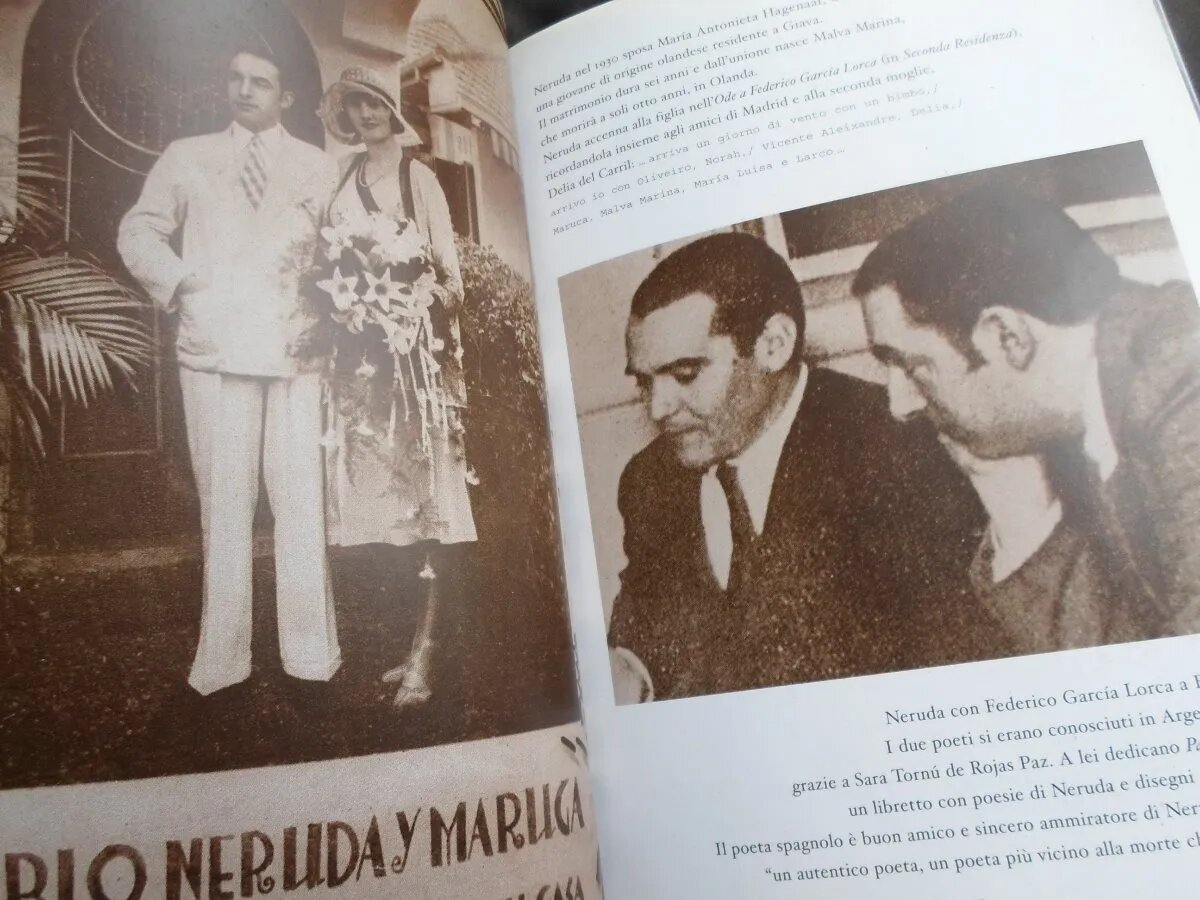

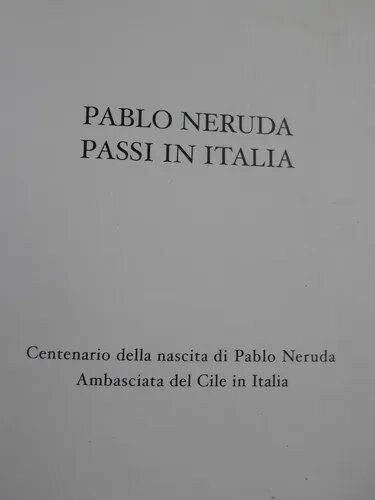

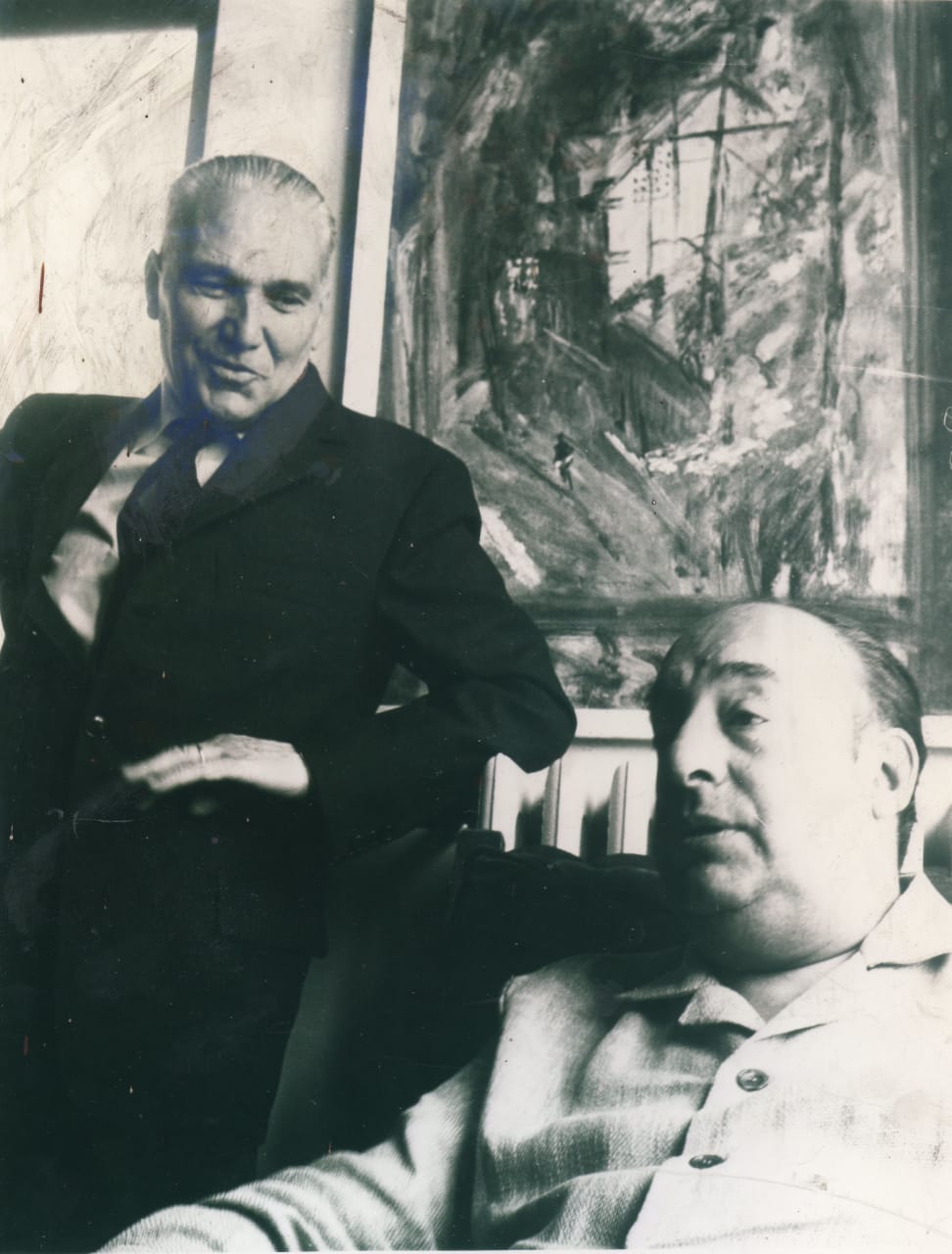

El poeta español Federico García Lorca y Pablo Neruda.

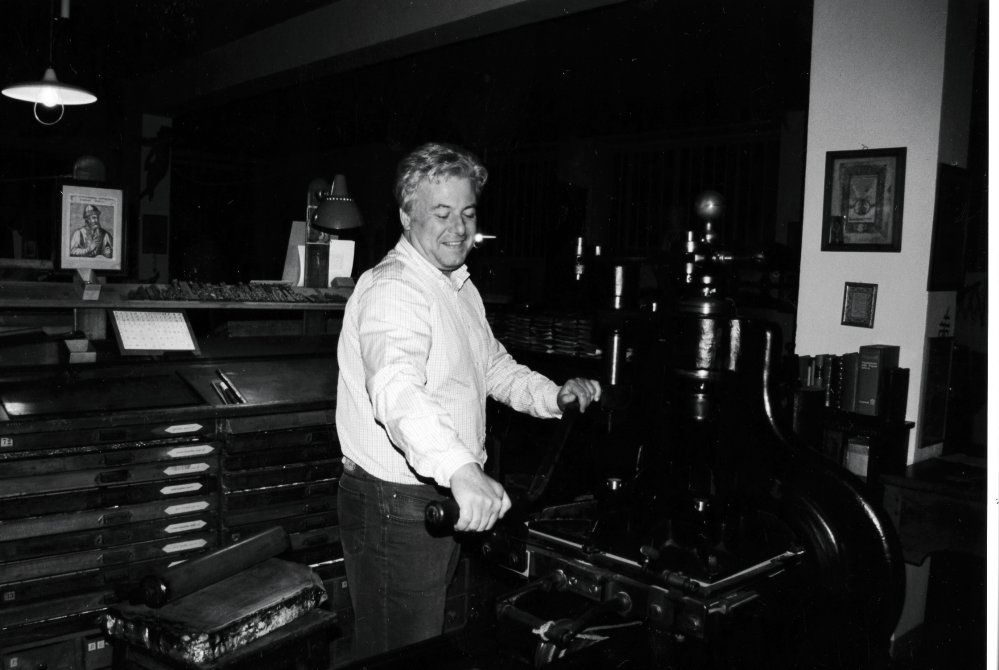

Giuseppe Bellini y Pablo Neruda en Milán.

Licenciado en Literatura y Doctor en Educación. Socio de la Sociedad de Bibliófilos Chilenos. Investigador de Booklife Asesorías Editoriales.

Le Pagine dell’Isola

Ignazio Cerio Capri Centre

These pages analyse some writings of Norman Douglas, Oscar Wilde and Pablo Neruda where the unique island of Capri is present. Its authors are Menichelli and Barattolo. They were published in 2003 by Giannini Press of Naples.

The particular beauty of the island and its people, an astonishing combination of peasant and maritime culture, has for centuries attracted various personalities who have enjoyed a unique enclave, a perfect setting for Pablo Neruda who arrives at the Marina Grande in 1952.

Pablo and Matilde settle in Arturo`s House in Vía Tragara, which is kindly loaned for a few months by Edwin Cerio, a protector and scholar of the island’s nature and a point of reference for the writers, artists and scientists who visited it.

The dark house becomes a luminous stage where Matilde is the bearer of light and happiness and, most importantly, becomes the clandestine refuge where her anonymous book The Captain’s Verses will end.

Remember when

in winter

we arrived to the island?

The sea raised toward us

A glass of cold (…)

You inhabited the house

What awaited you dark

And you lit the lamps then …

Menichelli and Barattolo’s text mainly analyses the idyllic figure of Capri in the Captain`s Verses, which sing with lyrical urgency a passionate and sensual love that represents a decisive stage in the artistic process and in the emotional life of the Poet. This sweet and passionate period lived intensely with the woman he loved in the island retreat is transformed, through dazzling poetry, into a happy and renewed expression of beauty and love.

Books

Neruda a Capri. Sogno di una isola.

I created you, I invented you in Italy …

I slept the whole night with you

by the sea, on the island.

Wild and sweet you were between pleasure and sleep,

between fire and water.

Neruda in Capri is a work by Teresa Cirillo Serri, professor of Hispanic American Literature at the Oriental University of Naples.

The book is divided into three chapters: Dreams of an Island, Lovers of Capri and Letters from Capri. In addition, it contains a selection of Neruda`s poems in Spanish and Italian inspired by the heavenly setting and by his lover, Matilde.

Neruda arrived in Capri at the beginning of 1952 because he was looking for a refuge to hide from political persecution and, also, to live his intense love with Matilde. His Italian friends help him so that he is not deported and so that he could live his romance with peace of mind.

The backdrop: the island of stone, moss, ivies, and vineyards in the rock, becomes one of the characters in this story that, told in an entertaining and documented way, recounts a six-month hiatus of joy from the couple in Capri, where for some time they lived in Arturo`s House, a small white house located in a beautiful natural setting, owned by the eminent intellectual and writer from Capri, Edwin Cerio.

The stay in Capri represents the first step towards Neruda’s indissoluble and definitive union with his clandestine love, a fact that is immortalized in the anonymous book The Captain’s Verses, co-financed by Italian personalities and intellectuals, and published in Naples in July 1952.

The reading of this story flows in a dynamic way, nuanced with aspects of the historical context, Neruda’s difficulties to obtain a temporary residence permit, the details of the idyllic love, the days of poetic creation, the meetings with friends and the walks through the hills and corners of the dream island.

Island, from your walls / I detached the little night flower / and I keep it on my chest. / And from the sea turning around you / I made a ring of water / that was left there in the waves, / enclosing the proud towers / of flowered stone, the cracked peaks / that my love held / and will keep with implacable hands / the footprint of my kisses. (The grapes and the wind))

Ex Libris. Encounters in Capri with men and books.

Claretta Cerio

How many things,

limes, thresholds, atlases, cups, nails,

they serve us like unspoken slaves,

blind and strangely stealthy!

They will last beyond our forgetfulness.

They will never know that we are gone.

Ex Libris describes notable characters who passed through the island of Capri. In the chapter dedicated to Pablo Neruda, its author, the Italian-German writer Claretta Wiedermann Cerio, characterizes him as a curious child surrounded by surprising and strange objects that made up his personal universe. This interest seemed to externalize the complex facets of his inner being: curiosity, fantasy, sensitivity, humour, passion.

In the house of Via Tragara he feels at ease, he acquires a sense of security and tranquillity, something that he had lacked until that moment, during his wandering existence as a political exile. At the same time a new life begins with Matilde.

In their Italian refuge, the lovers expressed an overflowing joy that it was necessary to share with those who could understand their language of madness and their complete departure from common sense. Edwin and Claretta got it. They had recently married and were expecting a daughter. At that moment they were infinitely happy and they also wanted to share their happiness, therefore, when all four where together there was a magical element that materialized in a brief and consummate happiness.

Some hint of that feeling can be seen in one of Neruda’s many messages to the couple that, Claretta says, can be read like poetry.

Dear Claretta and Edwin,

Unique friends,

our happiness

greet your happiness.

Tenderly

Pablo and Matilde.

Claretta and Edwin undoubtedly became essential figures in Pablo and Matilde’s life during their stay in Capri. His two dear friends and the dream island are the protagonists of the poem ¨Farewell to the Snow¨ in Memorial de Isla Negra.

Claretta became a prolific German novelist. He passed away in August 2019, at the age of 92.

Ignazio Delogu: Poesie e scritti in Italia.

Roma, Lato Side Editori, 1981.

I entered Florence. It was

night. I trembled listening

almost asleep to what the sweet river

told me.

Neruda’s Italian experience is part of the second period of his life and work. In 1949, during the First World Peace Congress in Paris, he reunited with some of his Italian friends and created new ties with others. Among them there were the main intellectuals who contributed to the spread of his art in Italy: Quasimodo, who translated a poetic anthology for Einaudi; Renato Guttuso who illustrated that anthology; Dario Puccini, who was the first Italian translator and scholar of his work and Mario Socrate who collaborated in the translations. The latter published Reading of Canto General in the Turin magazine Società (1950), where he offered the Italian readers the first critical elements for the knowledge of the poet’s work, which is an important fact because, until that moment, he was unknown in Italy.

Neruda’s first visit to Italy was brief, between October and November 1950. On that occasion, he toured Rome with Delia del Carril. This memory was enduring and was reflected in the poem ¨The Fruits¨ in Grapes and the Wind. It was during his second stay in Rome (December 12, 1950 – January 1951) that he met Mario Alicata and Paolo Ricci. This time, he began a trip to some Italian cities. Florence inspired ¨The Sweet River¨ and ¨The Golden Arno¨. In Turin, he was a guest of the Einaudi publishing house. The journey continued to Venice, Milan, and Genoa. In addition, he visited Gabriela Mistral in Rapallo, who at that time was Consul General of Chile.

Neruda returned to Naples at the end of 1951. In those days, a controversial order of expulsion from the country was revoked due to political pressure, and he was allowed to remain in Italy. He settled on the island of Capri, where he wrote most of The Grapes and the Wind and completed and edited the Captain’s Verses. The latter’s edition was Neapolitan and financed entirely by his friends, most of whom were Italian. It is a key book, according to Delogu, without which the life and work of the Poet would be difficult to understand because this pause in Capri allowed extraordinary concentration and encouraged a positive conception of life, beyond poetry.

According to Delogu, 1951 was Neruda’s Italian year. After the publication of ¨Wake up the Woodcutter¨ in Rinascita’s newspaper supplement, the poem was reproduced, disseminated, and widely commented on. Finally, on December 9, marking the end of the Italian poetic cycle, the newspaper L’Unita published it in full on its central page.

Although the first few years of the 1950s were the most significant in Neruda’s incipient relationship with Italy, it is in the 1960s when that relationship was consolidated with the publication of two anthologies: Poetry by Giuseppe Bellini (Milan, Nuova Academia, 1960) and Poetry by Dario Puccini (Florence, Sansoni, 1962). In addition, the anthology translated by Quasimodo was reedited, and was widely disseminated and became a publishing success.

Ignazio Delogu: Pablo Neruda e l’Italia 1949-1973

Motta & Caffiero, Nápoles, 2007.

The richness of Neruda’s poetry is due, among other factors, to the contributions of the various cultures of the countries through which he passed or lived. Italy is undoubtedly at the forefront of them, and Ignazio Delogu, a poet and his friend, reviews in this book the key moments that have linked Neruda to Italy. The work is mainly based on two aspects: the documented testimony of Neruda’s presence in Italy and the critical analysis of his poetry.

Towards the end of October 1950, during his first visit to Italy, Neruda travelled to Rome, where, once again, he met his friend Libero Bigiaretti and came into contact with Moravia, Elsa Morante, Guttuso, Debenedetti and with communist politicians such as Emilio Sereni and Ambrogio Donini. He also met Italian artists and intellectuals of a progressive left line such as Antonello Trombadori, Antonio Scordia, Galvano Della Volpe, Sibila Aleramo, Mario de Micheli and Saltvatore Quasimodo.

In the book, Neruda is described as a strong and independent person, with a dynamic sensual relationship with life, eternally animated by a curiosity that was not only intellectual, but also material. Guttuso remembers him walking through the streets and markets to buy decks of cards, shells and similar objects. For his part, Trombadori remembers him searching for books in the antique shops around Piazza di Spagna and the Roman College.

The “Rabelesian Disposition” of the Poet, his taste for learning about the material culture of the people who welcomed him and his enthusiasm for typical trattoria and Italian cuisine are underlined in the book. He is also frank and generous, but at the same vain and a tireless attention seeker. Mario Socrate says: “He was always surrounded by his court. It was evident that he considered himself the greatest poet in the world”.

Neruda visits Naples at a time of intense cultural activity, where there is a frenzy of renewal and rebirth. Here the friendship between the poet and Dario Puccini is reinforced, and he would become the main Italian scholar who studied his poetry and is an exemplary translator of Canto General. Puccini remembers, ¨ I was Neruda’s love postman, because I put the letters in the mailbox for Matilde. I remember him with emotion and irony. I was his first translator and the first to speak about him in Italy”.

Florence, Venice, Turin, and Genoa are other stages of the Neruda’s presence in Italy, where the poet not only interacts with artists and intellectuals, but also with people from the town, labourers, or simple militants of left-wing parties. During his poetry recitals in factories or crowded rooms, he is always monitored by the police.

Now Neruda intends to spend time in Capri, he receives an expulsion order. This fact provokes the indignation of intellectuals and politicians, but the decision is reversed, and he is authorised to reside in Italy for a few months. From that moment on, Matilde Urrutia enters his life permanently, as is testified in The Captain’s Verses.

Magazine “Nerudiana”, of the Pablo Neruda Foundation. Santiago de Chile, N ° 13-14, March-December 2012. Director: Hernán Loyola.

Congresses, conferences, magazines, book references. Commemorative events to mark the centenary of the birth of the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904-2004), “From the Mediterranean to the Oceans”. Newsletter N ° 16 (April 2005), in the care of Clara Camplani and Patrizia Spinato Bruschi. Università degli Studi di Milano.

Librarian, Master in Literature. Researcher of the project in Italy.

Neruda Illustrated

Pablo Neruda: 20 Love Poems and a Desperate Song.

Attilio Rossi was born in 1909 in Albairate and died in Milan in 1994. He made a pictorial journey throughout the 20th century, ranging from abstract art to hyper-realism, breaching the frontier of the most advanced figurative art, whilst taking into account the most important experiments in contemporary art.

He had a deep relationship with Hispanic and Latin American culture during his long stay in Argentina (1935-1950), where he was the first artistic director of Editorial Espasa Calpe and then, in 1938, founder of the Losada Press with Guillermo De Torre, Francisco Romero and Gonzalo Losada. He created the logo for the new press. He also illustrated numerous books and covers for the volumes in which he edited the publication.

During this intense editorial work, Attilio Rossi established relationships of collaboration and friendship with numerous Spanish intellectuals. Among his friends was Pablo Neruda, for whom he illustrated Twenty Love Poems and a Desperate Song.

Neruda’s Poems

We have here a painter and a poet, two sublime interpreters of the same skills: to reach hearts hungry for beauty; free them from apathy by dragging them into a storm of feeling; heal them from loneliness by connecting them with the secrets of the world. One with the speed and explosion of a brushstroke; the other with the persuasive sigh of the word. There was a great affinity between both artists, they had the same desperate melancholy, the truth and the scars of history, its gaps and its faults. The two lived almost parallel lives, although with an opposite development: the Sicilian, during his youth, knew the atrocities of Mussolini’s Italy, which he actively opposed through his early artistic works; The Chilean in 1973, at a rather advanced age, witnessed the precise moment of Pinochet’s dictatorial rise before losing his life just ten days later. In the meantime, they had a meeting that would keep them eternally consecrated as companions in the fight.

As early as 1952, in the edition of Neruda’s Poetry, published by the Einaudi publishing house, translated by Salvatore Quasimodo, the text was accompanied by Guttuso’s splendid illustrations, in ink and charcoal in rigorous black and white to represent the expressive urgency and at the same time the raw pain of reality, both in the poems and in the drawings. It is quite plausible to think that the two met in the most important European cultural circles of the time and, therefore, established a deep bond of friendship. As confirmation of this thesis, we find a curious and significant episode that took place in 1956 when Guttuso married his beloved muse and partner Mimise and for the occasion, Neruda not only dedicated a poem to them, but even participated as a witness to the wedding.

The confirmation of their link is the evidence that Guttuso himself was one of those who immediately suspected the falsity of the official version issued by the regime, according to which Neruda had lost his life due to a tumour. So much so that Guttuso hastened to send his friend a drawing made on cardboard, in which Neruda, whose pose recalls the Marat painted by David at the moment of death, holds for the last time in his right hand his inseparable pen, a peaceful weapon of liberation and symbol universal rejection of all oppression. On the left, a page has an eloquent inscription: “Nixon Frei Pinochet” that Neruda himself had accused in his last poem, “The Satraps”. At the bottom of the card – from which an engraving was taken in Santiago de Chile, described by Salvatore Settis in an article published in “Il Sole 24 Ore” in 2013 – a simple, but moving farewell: “To Pablo, Renato “.1.

1 https://www.sicilianpost.it/il-mistero-della-morte-di-neruda-svelato-da-unopera-di-guttuso/

Neruda “literary character”

Some novels of recent publication have been inspired by various episodes in Neruda’s life: this is how he has become the protagonist.